Three new findings show us the way of our trails

By Nick Falbo, August 28 2013

In the Portland/Vancouver region, we’re proud of the nature in our backyard. This love of nature ties our cities and counties together, literally, in the form of The Intertwine – our shared system of trails, parks and natural areas.

In the Portland/Vancouver region, we’re proud of the nature in our backyard. This love of nature ties our cities and counties together, literally, in the form of The Intertwine – our shared system of trails, parks and natural areas.

But who’s actually using our trails? How many of us? And why? For one week each September, Metro mobilizes a small army of dedicated volunteers for Trail Counts that attempt to answer these very questions. In a two-hour count session, volunteers armed with clipboard at dozens of key trail locations across the metro region record when someone passes their line, their mode of transportation, and their gender. Through this collective effort, we can document changing patterns of trail use, provide data to support future trail investments, and shed light on who in The Intertwine is taking most advantage of our great trails network.

But who’s actually using our trails? How many of us? And why? For one week each September, Metro mobilizes a small army of dedicated volunteers for Trail Counts that attempt to answer these very questions. In a two-hour count session, volunteers armed with clipboard at dozens of key trail locations across the metro region record when someone passes their line, their mode of transportation, and their gender. Through this collective effort, we can document changing patterns of trail use, provide data to support future trail investments, and shed light on who in The Intertwine is taking most advantage of our great trails network.

Following methods recommended by the National Bicycle and Pedestrian Documentation Project, Metro has collected trail use data since 2008. Recently we crunched Metro's historic trail count database to compare user volumes between trails, extrapolate two hour counts into annual totals, and tease out trail corridor trends and patterns for a just-released Intertwine trail use snapshot. What did we learn? Among other things, the following three findings:

Following methods recommended by the National Bicycle and Pedestrian Documentation Project, Metro has collected trail use data since 2008. Recently we crunched Metro's historic trail count database to compare user volumes between trails, extrapolate two hour counts into annual totals, and tease out trail corridor trends and patterns for a just-released Intertwine trail use snapshot. What did we learn? Among other things, the following three findings:

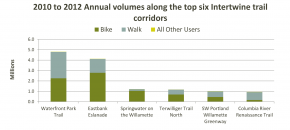

1) Riverfront Trails are the Most Popular

Five of The Intertwine's top six highest use trails are located along the Willamette or Columbia Rivers. The Waterfront Park Trail and the Eastbank Esplanade in downtown Portland lead the pack by far, with over three times the volume of the next highest use trail: the Springwater Corridor along the Willamette River.

Five of The Intertwine's top six highest use trails are located along the Willamette or Columbia Rivers. The Waterfront Park Trail and the Eastbank Esplanade in downtown Portland lead the pack by far, with over three times the volume of the next highest use trail: the Springwater Corridor along the Willamette River.

2) Everyone Walks

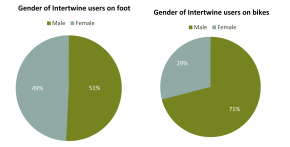

Gender is balanced among walkers on The Intertwine. While people tallied on foot are split evenly between male and female, the numbers for cyclists are significantly more lopsided, with females accounting for just 29 percent of riders. A note that this number is for the Intertwine system as a whole; data for some corridors evidenced a more equitable gender distribution. For example, 43 percent of the observed users on Clark County's Columbia River Renaissance Trail were female.

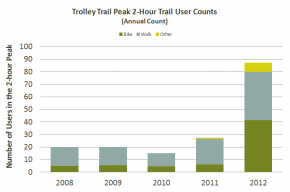

3) If You Build It, They Will Come

The story of the Trolley Trail makes a great case for building and enhancing trails in our communities. Until 2012, the so-called Trolley Trail was a brambly pathway along an abandoned trolley line in Milwaukie. While in use by neighborhood pedestrians over the decades following the trolley era's sunset in the 1950s, the Trolley Trail failed to live up to its full potential as a transportation and recreation corridor, with a pathway muddy most months of the year and overgrown with blackberries and other weeds.

The story of the Trolley Trail makes a great case for building and enhancing trails in our communities. Until 2012, the so-called Trolley Trail was a brambly pathway along an abandoned trolley line in Milwaukie. While in use by neighborhood pedestrians over the decades following the trolley era's sunset in the 1950s, the Trolley Trail failed to live up to its full potential as a transportation and recreation corridor, with a pathway muddy most months of the year and overgrown with blackberries and other weeds.

In 2012, the Trolley Trail was developed into a fully paved shared-use path to conform to national standards. The change in atmosphere was significant, with usage levels boosted to match. The huge increase in use over 2012 offers us a promising peek at the potential of other similarly unfinished trail corridors – for example, the North Portland Greenway.

In 2012, the Trolley Trail was developed into a fully paved shared-use path to conform to national standards. The change in atmosphere was significant, with usage levels boosted to match. The huge increase in use over 2012 offers us a promising peek at the potential of other similarly unfinished trail corridors – for example, the North Portland Greenway.

So what should we take from these three initial findings from Metro Trail Count data? We know that trails enhance communities across The Intertwine through access to nature, opportunities for physical activity, and options for transportation. And we know that counting counts – helping us track where we've been, learn from past successes, and forge ahead with new trails. We don't yet know where trail count data will lead. But if you join us Sept. 10-15, you can help inform that future.

Nick Falbo is a planner at

Nick Falbo is a planner at

Add new comment