Connected green space, coho & community spirit

By Daniel Newberry, April 1 2015

For the past century, cities have been built to encourage automobile traffic. This model generally excludes green spaces, which are so vital for our mental health and spiritual well-being. What I find so thrilling about the Portland area—and the work of The Intertwine partners in particular—is using green space as the basis for building a new transportation paradigm for non-motorized travel.

For the past century, cities have been built to encourage automobile traffic. This model generally excludes green spaces, which are so vital for our mental health and spiritual well-being. What I find so thrilling about the Portland area—and the work of The Intertwine partners in particular—is using green space as the basis for building a new transportation paradigm for non-motorized travel.

I’ve lived in several cities and have found that parks and trails are something you use your auto—rather than your legs—to reach. Many cities are desperately seeking solutions to change this transportation paradigm, and Portland is leading the way. I’m excited to be part of that.

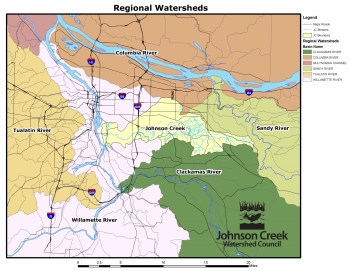

When I moved here recently to take my job with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council, which I started in February, I came from the rural Applegate Valley in southern Oregon. Walking out my back door into the woods, and running or hiking trails, is part of who I am. So is stream and forest restoration, my career for the past 24 years. I am relieved that green spaces are still close by.

It comes as a welcome surprise, then, that the focus of my new work—Johnson Creek—lies in such an important green-space corridor. Paralleling and crossing the pedestrian/bicyclist Springwater Corridor for so many miles, this stream connects such green gems as the Tideman-Johnson Natural Area, Brookside and Beggars Tick wetlands, and Powell Butte Nature Park. Take a detour on the Gresham-Fairview Trail and you’ll pass through and by several more parks. The beauty of this network is how far you can travel without a combustion engine and still be in green space.

It comes as a welcome surprise, then, that the focus of my new work—Johnson Creek—lies in such an important green-space corridor. Paralleling and crossing the pedestrian/bicyclist Springwater Corridor for so many miles, this stream connects such green gems as the Tideman-Johnson Natural Area, Brookside and Beggars Tick wetlands, and Powell Butte Nature Park. Take a detour on the Gresham-Fairview Trail and you’ll pass through and by several more parks. The beauty of this network is how far you can travel without a combustion engine and still be in green space.

In the past 20 years, millions of dollars have been invested in restoration of the Johnson Creek stream network and its riparian forest. The results are evident. For such an urbanized watershed, Johnson Creek is unique in our area in serving as a  spawning ground for threatened coho salmon. Chinook salmon, steelhead trout, and cutthroat trout also spawn here. Beaver build dams in Johnson Creek.

spawning ground for threatened coho salmon. Chinook salmon, steelhead trout, and cutthroat trout also spawn here. Beaver build dams in Johnson Creek.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for fish that spawn in our watershed is swimming through culverts. In a recent surveying project, our Council documented that 202 of 273 stream crossings interfered with fish migration. One of the top priorities in our new 10-year action plan is to address some of these fish passage issues. For me, one of the most thrilling streamside experiences is to watch salmon spawn. We’d like more people to have that experience.

There’s a palpable excitement and spirit of volunteerism in our metro area around participating in this restoration effort. Last year, more than 1,300 individuals volunteered to plant trees, remove invasive vegetation, monitor stream conditions and clean up garbage in the Johnson Creek stream corridor through our Council’s projects. To me, this groundswell speaks not only to the hunger to be around healthy natural areas, but to be part of a community that shares these values, as well.

There’s a palpable excitement and spirit of volunteerism in our metro area around participating in this restoration effort. Last year, more than 1,300 individuals volunteered to plant trees, remove invasive vegetation, monitor stream conditions and clean up garbage in the Johnson Creek stream corridor through our Council’s projects. To me, this groundswell speaks not only to the hunger to be around healthy natural areas, but to be part of a community that shares these values, as well.

Through an existing bond measure, new green-space acquisitions continue all over our area. Johnson Creek has certainly benefited! I’m excited and proud to be part of such a large and cooperative effort to restore streams and green spaces in the Johnson Creek Watershed. I look forward to exploring them.

Daniel Newberry is the executive director of the Johnson Creek Watershed Council. He moved to Oregon in 1993 after earning a master’s degree in forest science, concentrating in forest hydrology and watershed management. He has also served as the executive director of the Applegate River Watershed Council and the Siskiyou Field Institute, and has worked as a tribal and federal hydrologist, and as a consultant.

Daniel Newberry is the executive director of the Johnson Creek Watershed Council. He moved to Oregon in 1993 after earning a master’s degree in forest science, concentrating in forest hydrology and watershed management. He has also served as the executive director of the Applegate River Watershed Council and the Siskiyou Field Institute, and has worked as a tribal and federal hydrologist, and as a consultant.

Add new comment