How far upstream do coho and steelhead swim in Portland’s only free-flowing salmon stream, Johnson Creek? How does floodplain restoration reduce flooding downstream? Answers to these questions and much more can be found in the 2012 Johnson Creek State of the Watershed Report, just published by the Johnson Creek Watershed Council (JCWC). The glossy six-pager highlights the most current scientific information about Johnson Creek using maps and features recent restoration projects. It’s focused on four topic areas: fish and wildlife, stream temperature, seasonal streamflow, and water pollution.

“In a nutshell, there is much more to do in terms of ecological recovery, but the research also shows that Johnson Creek is resilient,” says JCWC Restoration Coordinator, Robin Jenkinson.

JCWC last published a State of the Watershed Report in 2008. Since then, a group called the Johnson Creek InterJurisdictional Committee (IJC) worked together to collect the wealth of new information included in the Report and provided invaluable assistance in its development. The IJC includes technical representatives from the Cities of Portland, Gresham, Milwaukie, and Damascus, Multnomah and Clackamas Counties, East Multnomah and Clackamas County Soil and Water Conservation Districts, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, Oregon Department of Agriculture, the US Geological Survey, and the Johnson Creek Watershed Council.

“We’ve forged a successful model for collaborative watershed science here,” Jenkinson asserts. “We know so much more about Johnson Creek now than we did even four years ago.”

For example, in 2011-2012, Multnomah County led a fish survey of upper Johnson Creek and its tributaries, finding native fish species in nearly every tributary surveyed, even in the small, intermittent streams. For the last two years, wild coho salmon have been seen spawning over 15 miles up Johnson Creek near Gresham.

Another of the Report’s key findings is that, during the summer, most of the mainstem of Johnson Creek is too hot for rearing salmon and trout -- exceeding the state water quality standard of 64.4 degrees Fahrenheit. Young fish may be finding refuge in tree-shaded tributaries and areas with groundwater springs.

This compiled information will give scientists, environmental managers, and local officials a sound scientific basis to make informed decisions about how to continue improving Johnson Creek. “Management of Johnson Creek is moving from a place where we didn’t have full knowledge of the creek, but had to create a plan for action. Now, we’re fleshing out our understanding at a watershed scale to get a sense of the whole,” adds Jenkinson.

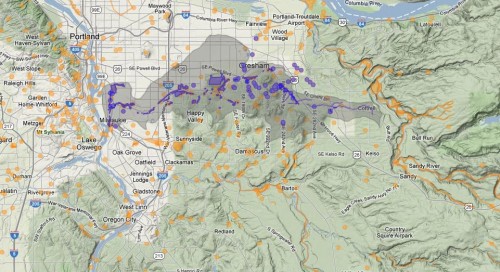

Johnson Creek is 26 miles long and runs from Boring and Damascus, through Gresham and Portland, until it reaches the Willamette River in Milwaukie, upstream of the Sellwood Bridge. The 52-square-mile urban Watershed is home to

threatened and endangered species including salmon, red-legged frogs, and painted turtles.