The gray-haired conservationist

How I answer the question of legacy

By Roberta Schwarz

“Yeah, but who is going to keep this going when you’re dead?”

“Yeah, but who is going to keep this going when you’re dead?”

Now there’s a question you don’t hear every day. But there it was, recently directed at me from a group member during a recent tour of West Linn’s White Oak Savanna -- a natural site my husband and I have been working to restore since 2005.

Blunt but interesting, I thought. Because when think about it, this question is something that all of us in the Intertwine (not just those of us with gray hair), should probably ask ourselves more often.

After all, legacy hits at the core of why we conservationists do what we do. Whether we get paid for our work, or volunteer our time, our shared motive is to leave something worth protecting over centuries. While fundraising, politics, and community organizing are certainly important, the ultimate key to our success (or failure) is whether we can spark a fire in the bellies of our children to serve as stewards of the land after we’re gone.

After all, legacy hits at the core of why we conservationists do what we do. Whether we get paid for our work, or volunteer our time, our shared motive is to leave something worth protecting over centuries. While fundraising, politics, and community organizing are certainly important, the ultimate key to our success (or failure) is whether we can spark a fire in the bellies of our children to serve as stewards of the land after we’re gone.

Especially if the land you’re protecting offers them something in danger of vanishing forever. For over 10 years, many volunteers have helped our small nonprofit, Neighbors for a Livable West Linn, begin to restore the upper 14 of the 20 acres of a rare and majestic spot called the White Oak Savanna.

Today, only two percent remains of the 600,000 acres of White Oak habitat that once stretched up and down the Willamette Valley. Of those 12,000 acres, just one percent is publicly owned -- like our little patch of Savanna. Conserving this beautiful Savanna has to date entailed over 6,800 hours of restoration work, dozens of fundraisers, and plenty of tours -- like the one I mentioned above -- to get the community excited.

Today, only two percent remains of the 600,000 acres of White Oak habitat that once stretched up and down the Willamette Valley. Of those 12,000 acres, just one percent is publicly owned -- like our little patch of Savanna. Conserving this beautiful Savanna has to date entailed over 6,800 hours of restoration work, dozens of fundraisers, and plenty of tours -- like the one I mentioned above -- to get the community excited.

But yes, we’ve also taken care to weave kids into our effort. They have worked with us on school plantings, Scout and NW Youth Corps projects, PSU work parties, SOLVE events. They’ve had first sightings with us of coyotes and blue camas. They’ve hopped on tree swings, and come to love this land with us. They are quick studies.

And lately, they show us how it’s done. Young students at a local after-school Camp Fire program at Trillium Creek Primary are now busy doing their own fundraisers for the protection of the lower six acres of our White Oak Savanna. They call themselves the White Oak Savanna Committee.

And lately, they show us how it’s done. Young students at a local after-school Camp Fire program at Trillium Creek Primary are now busy doing their own fundraisers for the protection of the lower six acres of our White Oak Savanna. They call themselves the White Oak Savanna Committee.

As a social worker and teacher for more than 35 years, what gives me hope at the end of the day is the potential of our kids to make things better. In classrooms today, I hear kids who are more liberal in their thinking and more accepting of each other than the students I went to school with dozens of years ago.

So when a young person serving me at the local pizza spot remembers me working with their class two years ago, to plant a thousand blue camas bulbs, I feel reassured that we gray-haired conservationists will be leaving The Intertwine in good hands.

So when a young person serving me at the local pizza spot remembers me working with their class two years ago, to plant a thousand blue camas bulbs, I feel reassured that we gray-haired conservationists will be leaving The Intertwine in good hands.

Because as I told the site visitor who asked about legacy that day in the Savanna: “It’s the kids who are going to keep things going.”

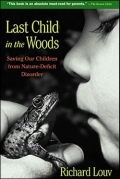

Kurt Beil, ND, LAc, MPH is a holistic physician and researcher at the

Kurt Beil, ND, LAc, MPH is a holistic physician and researcher at the  Richard Louv’s bestselling book

Richard Louv’s bestselling book

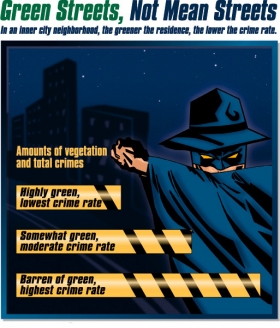

Older African American generations have passed down intense accounts of slaves on the run, and terrifying stories of lynching, adding a dimension of dread and fear to the solitude of the woods, rather than wonder, excitement, and exploration. And for inner-city children, the privilege of experiencing nature is further impeded by inaccessibility, surviving the hustle of the streets, and parents working harder than ever with multiple shifts for dwindling paychecks. When time and cost become impediments, the outdoors unfortunately becomes a luxury.

Older African American generations have passed down intense accounts of slaves on the run, and terrifying stories of lynching, adding a dimension of dread and fear to the solitude of the woods, rather than wonder, excitement, and exploration. And for inner-city children, the privilege of experiencing nature is further impeded by inaccessibility, surviving the hustle of the streets, and parents working harder than ever with multiple shifts for dwindling paychecks. When time and cost become impediments, the outdoors unfortunately becomes a luxury. I believe the magical, life-altering experiences offered by the outdoors can be a game-changer for inner-city children of color. Through the New Currents, Outdoors program, my goal is not just to establish a series adventurous expeditions that offer escape from the pressures of the city. I hope to make a lasting difference in the life of youth by connecting them with talented mentors and volunteers – an older generation who can teach life skills and inspire as role models for years to come.

I believe the magical, life-altering experiences offered by the outdoors can be a game-changer for inner-city children of color. Through the New Currents, Outdoors program, my goal is not just to establish a series adventurous expeditions that offer escape from the pressures of the city. I hope to make a lasting difference in the life of youth by connecting them with talented mentors and volunteers – an older generation who can teach life skills and inspire as role models for years to come. Chad Brown is the CEO/Creative Director of

Chad Brown is the CEO/Creative Director of

Had things gone differently, Thurman Street would have continued into the forest as the spine of a 1930s subdivision, one that would have replaced the deep woods with large homes. The failure of this Depression-era development saw these steep lots end up in city hands as payment in lieu of back taxes, and eventually subsumed into

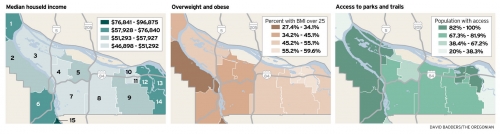

Had things gone differently, Thurman Street would have continued into the forest as the spine of a 1930s subdivision, one that would have replaced the deep woods with large homes. The failure of this Depression-era development saw these steep lots end up in city hands as payment in lieu of back taxes, and eventually subsumed into  But where are the Forest Parks of the future? Despite

But where are the Forest Parks of the future? Despite  As an urban planner, I often try to provide connections to nature in town and neighborhood plans. Even something as simple as a trailhead sign and a narrow path can suffice to entice us into the tangled, mysterious world beyond. A popular trend in landscape architecture features the design of children’s “nature-play” areas, which mimic unstructured, unsupervised forest adventures. As fabricated, ersatz nature, this is not ideal. But isn’t it better than screen time?

As an urban planner, I often try to provide connections to nature in town and neighborhood plans. Even something as simple as a trailhead sign and a narrow path can suffice to entice us into the tangled, mysterious world beyond. A popular trend in landscape architecture features the design of children’s “nature-play” areas, which mimic unstructured, unsupervised forest adventures. As fabricated, ersatz nature, this is not ideal. But isn’t it better than screen time? Ken Pirie is an associate with

Ken Pirie is an associate with

Mickey Fearn has been in the parks, recreation and conservation profession for over 45 years. Prior to serving as the

Mickey Fearn has been in the parks, recreation and conservation profession for over 45 years. Prior to serving as the