My bar for summer livability was set high when I moved to Boise, Idaho, after graduating  from college. The Boise River, which flows through the middle of town, is the lifeblood of the city. Locals not only kayak, inner-tube and fish the river, they also swim in it. And the City of Boise, recognizing the energy and value that this beloved river provides its citizenry, has made major efforts to cultivate its greatness, even opening a whitewater park north of downtown earlier this spring.

from college. The Boise River, which flows through the middle of town, is the lifeblood of the city. Locals not only kayak, inner-tube and fish the river, they also swim in it. And the City of Boise, recognizing the energy and value that this beloved river provides its citizenry, has made major efforts to cultivate its greatness, even opening a whitewater park north of downtown earlier this spring.

After three years in the City of Trees, I moved to Portland for a job. In 1998, Portland was gaining national attention for its “green,” fresh-thinking culture. Yet almost upon arrival, I was put on notice that “nobody swims in the Willamette…it is a toilet...a superfund site.”

My reaction was outrage, then disappointment. It made no sense that a city billed as the “greenest city in the U.S.” had a polluted river running through the center of town. And  I found it baffling that people simply made jokes, doing little to change it. I realized that naively, I had both overestimated Portland and underestimated Boise. Even today, after fifteen years in Portland, I think of Boise as the Paris of metropolitan river park systems. I am, however, heartened by a swell of activism that promises to transform our own urban river culture.

I found it baffling that people simply made jokes, doing little to change it. I realized that naively, I had both overestimated Portland and underestimated Boise. Even today, after fifteen years in Portland, I think of Boise as the Paris of metropolitan river park systems. I am, however, heartened by a swell of activism that promises to transform our own urban river culture.

In November 2011, the City of Portland completed a $1.44 billion, 20-year project, 100% funded by ratepayers, called The Big Pipe. Many in Portland have heard about The Big Pipe, and many of these people know that it’s now complete. However, too few understand how successful this engineering marvel has been, and what this success could mean for all of us.

Very simply, The Big Pipe was created to control sewage overflows into the Willamette  River. Before The Big Pipe project was complete it would only take 1/10 of an inch of rain to cause raw sewage to overflow into the Willamette River. Historically, this disgusting occurrence would occur 100 times -- or more -- every year, so after completion in 2011, it didn’t take very long for The Big Pipe to be tested. And yet last March, the wettest in recorded city history, we experienced not one sewage overflow the entire month. Passing this test, it’s likely that Portland may not ever again experience a summertime sewage overflow in the Willamette River.

River. Before The Big Pipe project was complete it would only take 1/10 of an inch of rain to cause raw sewage to overflow into the Willamette River. Historically, this disgusting occurrence would occur 100 times -- or more -- every year, so after completion in 2011, it didn’t take very long for The Big Pipe to be tested. And yet last March, the wettest in recorded city history, we experienced not one sewage overflow the entire month. Passing this test, it’s likely that Portland may not ever again experience a summertime sewage overflow in the Willamette River.

The significance of this? That it’s safe to swim in the Willamette River! Whether a Portland  native, or a transplant, like me, you may find this hard to believe. Therefore, I encourage you to do some simple research and develop your own opinion. Don’t just accept carte blanche the words of someone who told you our river was polluted when you moved here. Or, for Portland natives, I challenge you to consider the notion that we the people can change a river. We can reclaim it, restore it, and develop it wisely for recreational use. The Willamette is not the same river it was 20 years ago.

native, or a transplant, like me, you may find this hard to believe. Therefore, I encourage you to do some simple research and develop your own opinion. Don’t just accept carte blanche the words of someone who told you our river was polluted when you moved here. Or, for Portland natives, I challenge you to consider the notion that we the people can change a river. We can reclaim it, restore it, and develop it wisely for recreational use. The Willamette is not the same river it was 20 years ago.

In Portland, enjoying our short but sublime summer is something we embrace with an artist’s intensity. But for too long, those summers have been missing one elemental ingredient. Something right under our toes can transform our city forever, make Portland the world class city we all want it to be, and exponentially increase our quality of life. That’s right, the Willamette River. So, grab some friends and go take a dip. We paid a lot of money to clean up the Willamette, and now it’s time to collect our river dividend.

In Portland, enjoying our short but sublime summer is something we embrace with an artist’s intensity. But for too long, those summers have been missing one elemental ingredient. Something right under our toes can transform our city forever, make Portland the world class city we all want it to be, and exponentially increase our quality of life. That’s right, the Willamette River. So, grab some friends and go take a dip. We paid a lot of money to clean up the Willamette, and now it’s time to collect our river dividend.

The Portland Harbor cleanup has been the subject of much attention lately, including here at Willamette Riverkeeper, and with good reason. There’s a lot at stake with the Superfund project, and we’ll need to continue to engage to get the best result for this vital stretch of the Willamette.

The Portland Harbor cleanup has been the subject of much attention lately, including here at Willamette Riverkeeper, and with good reason. There’s a lot at stake with the Superfund project, and we’ll need to continue to engage to get the best result for this vital stretch of the Willamette.

2) Restoring habitat in the heart of the city. We can do this today. Even small nodes of floodplain and healthy riverside habitat can provide tangible benefits for fish, birds and mammals. Throughout significant portions of the City, the riverside is rock and concrete, which does little for fish and wildlife. We can soften this hardscape at multiple urban locations, such as portions of the Bowl at Waterfront Park, and immediately improve shallow water habitat for threatened fish like Spring Chinook.

2) Restoring habitat in the heart of the city. We can do this today. Even small nodes of floodplain and healthy riverside habitat can provide tangible benefits for fish, birds and mammals. Throughout significant portions of the City, the riverside is rock and concrete, which does little for fish and wildlife. We can soften this hardscape at multiple urban locations, such as portions of the Bowl at Waterfront Park, and immediately improve shallow water habitat for threatened fish like Spring Chinook. 4) Moving Interstate-5. This is the big one on my list, but well worth a renewed conversation. It is time to begin to plan to move the Interstate 5 freeway away from the river, or to feed the freeway through a tunnel, or to cover a portion of it. Altering or moving the Marquam Bridge could also be part of the solution for an issue seen - and heard - by anyone who spends a few moments in the heart of the City.

4) Moving Interstate-5. This is the big one on my list, but well worth a renewed conversation. It is time to begin to plan to move the Interstate 5 freeway away from the river, or to feed the freeway through a tunnel, or to cover a portion of it. Altering or moving the Marquam Bridge could also be part of the solution for an issue seen - and heard - by anyone who spends a few moments in the heart of the City. by removing the Alaskan Way Viaduct. And Seoul, South Korea removed five kilometers of freeway in the heart of the city, uncovering a small river now accessible to all.

by removing the Alaskan Way Viaduct. And Seoul, South Korea removed five kilometers of freeway in the heart of the city, uncovering a small river now accessible to all.

Travis Williams is Executive Director and Riverkeeper for

Travis Williams is Executive Director and Riverkeeper for

From the depot, cyclists will also have access to other outdoor activities such as kayaking and jet boating to the base of Willamette Falls, whitewater rafting down the lower Clackamas, and paddling on stand-up boards in the

From the depot, cyclists will also have access to other outdoor activities such as kayaking and jet boating to the base of Willamette Falls, whitewater rafting down the lower Clackamas, and paddling on stand-up boards in the  Blane Meier is the owner of

Blane Meier is the owner of

Cassie Cohen is the executive director of

Cassie Cohen is the executive director of  Richard Louv’s bestselling book

Richard Louv’s bestselling book

Older African American generations have passed down intense accounts of slaves on the run, and terrifying stories of lynching, adding a dimension of dread and fear to the solitude of the woods, rather than wonder, excitement, and exploration. And for inner-city children, the privilege of experiencing nature is further impeded by inaccessibility, surviving the hustle of the streets, and parents working harder than ever with multiple shifts for dwindling paychecks. When time and cost become impediments, the outdoors unfortunately becomes a luxury.

Older African American generations have passed down intense accounts of slaves on the run, and terrifying stories of lynching, adding a dimension of dread and fear to the solitude of the woods, rather than wonder, excitement, and exploration. And for inner-city children, the privilege of experiencing nature is further impeded by inaccessibility, surviving the hustle of the streets, and parents working harder than ever with multiple shifts for dwindling paychecks. When time and cost become impediments, the outdoors unfortunately becomes a luxury. I believe the magical, life-altering experiences offered by the outdoors can be a game-changer for inner-city children of color. Through the New Currents, Outdoors program, my goal is not just to establish a series adventurous expeditions that offer escape from the pressures of the city. I hope to make a lasting difference in the life of youth by connecting them with talented mentors and volunteers – an older generation who can teach life skills and inspire as role models for years to come.

I believe the magical, life-altering experiences offered by the outdoors can be a game-changer for inner-city children of color. Through the New Currents, Outdoors program, my goal is not just to establish a series adventurous expeditions that offer escape from the pressures of the city. I hope to make a lasting difference in the life of youth by connecting them with talented mentors and volunteers – an older generation who can teach life skills and inspire as role models for years to come. Chad Brown is the CEO/Creative Director of

Chad Brown is the CEO/Creative Director of  Twenty-five years ago, Jack Churchill, public administration prof at PSU, called to offer some advice. It wasn’t plastics, like Dustin Hoffman's mentor in The Graduate. No, it was CLEAN WATER ACT! Park and wildlife biologists, he yelled, had neither the power nor funding to clean up the Willamette River and bring nature back into the city. I had just taken the position of Urban Naturalist at the Audubon Society of Portland and both of these were my primary goals. “Thanks for sharing,” I said and hung up, wondering what the Clean Water Act had to do with my mission.

Twenty-five years ago, Jack Churchill, public administration prof at PSU, called to offer some advice. It wasn’t plastics, like Dustin Hoffman's mentor in The Graduate. No, it was CLEAN WATER ACT! Park and wildlife biologists, he yelled, had neither the power nor funding to clean up the Willamette River and bring nature back into the city. I had just taken the position of Urban Naturalist at the Audubon Society of Portland and both of these were my primary goals. “Thanks for sharing,” I said and hung up, wondering what the Clean Water Act had to do with my mission. It took me a few years to get it. Sewer and stormwater agencies had immense potential to protect the region’s streams, rivers and watersheds. They had a federal mandate -- the Clean Water Act. Despite the fact that in the early 1980s they focused virtually exclusively on piped, engineered gray infrastructure solutions to water quality problems I realized the potential they held for moving the dial on urban greenspaces by integrating their mandates and mission with those of park providers and fish and wildlife agencies.

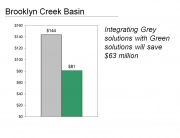

It took me a few years to get it. Sewer and stormwater agencies had immense potential to protect the region’s streams, rivers and watersheds. They had a federal mandate -- the Clean Water Act. Despite the fact that in the early 1980s they focused virtually exclusively on piped, engineered gray infrastructure solutions to water quality problems I realized the potential they held for moving the dial on urban greenspaces by integrating their mandates and mission with those of park providers and fish and wildlife agencies. Three decades on, and Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) is one of the most progressive, innovative stormwater agencies in the country. Thanks in part to the federal Clean Water Act, and to progressive leadership in the city, BES has broadened its mission. To be honest it took a lot of nudging and cajoling from local nonprofits like mine. But they have embraced green infrastructure and creative approaches to stormwater management.

Three decades on, and Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) is one of the most progressive, innovative stormwater agencies in the country. Thanks in part to the federal Clean Water Act, and to progressive leadership in the city, BES has broadened its mission. To be honest it took a lot of nudging and cajoling from local nonprofits like mine. But they have embraced green infrastructure and creative approaches to stormwater management. Unfortunately, no good deed goes unpunished. Some of our worst polluters and opponents of the city’s environmental programs have launched an initiative that would gut these programs and wrest control of BES from the city. Who would control their special “water utility"? The very same people who have polluted our waterways. BES is where we need it now: an important part of Portland’s collective efforts to protect nature in the city. The agency is accountable to us, not an obscure board, outside city control. Don’t Sign That Petition! It’s bad for the environment. It’s bad for public involvement. It’s bad for our water.

Unfortunately, no good deed goes unpunished. Some of our worst polluters and opponents of the city’s environmental programs have launched an initiative that would gut these programs and wrest control of BES from the city. Who would control their special “water utility"? The very same people who have polluted our waterways. BES is where we need it now: an important part of Portland’s collective efforts to protect nature in the city. The agency is accountable to us, not an obscure board, outside city control. Don’t Sign That Petition! It’s bad for the environment. It’s bad for public involvement. It’s bad for our water. For more information, and to get involved in opposing this

For more information, and to get involved in opposing this  Mike Houck directs the

Mike Houck directs the

River. Before The Big Pipe project was complete it would only take 1/10 of an inch of rain to cause raw sewage to overflow into the Willamette River. Historically, this disgusting occurrence would occur 100 times -- or more -- every year, so after completion in 2011, it didn’t take very long for The Big Pipe to be tested. And yet last March, the

River. Before The Big Pipe project was complete it would only take 1/10 of an inch of rain to cause raw sewage to overflow into the Willamette River. Historically, this disgusting occurrence would occur 100 times -- or more -- every year, so after completion in 2011, it didn’t take very long for The Big Pipe to be tested. And yet last March, the

Will Levenson is co-owner of

Will Levenson is co-owner of

ever seen. At the confluence of the Columbia, I course calmly through

ever seen. At the confluence of the Columbia, I course calmly through

Sam Drevo first competed in whitewater kayaking at age 15, as a Team USA member at the Jr. World Championships in Norway. Closer to home, Sam won the 2001 Ford Gorge Games Outdoor World Championship in Extreme Kayaking. When not traveling the world, Sam teaches paddlers of all levels as owner of eNRG Kayaking in Oregon City. Sam holds a Bachelor of Arts in Business from Lewis & Clark College.

Sam Drevo first competed in whitewater kayaking at age 15, as a Team USA member at the Jr. World Championships in Norway. Closer to home, Sam won the 2001 Ford Gorge Games Outdoor World Championship in Extreme Kayaking. When not traveling the world, Sam teaches paddlers of all levels as owner of eNRG Kayaking in Oregon City. Sam holds a Bachelor of Arts in Business from Lewis & Clark College.