Language of love

Can biophilia capture the heart of our cities?

Ramona DeNies

Timothy Beatley's Biophilic Cities Project is proof that one word can start a global conversation.

Timothy Beatley's Biophilic Cities Project is proof that one word can start a global conversation.

Just six months ago, Beatley, a professor of sustainable communities at the University of Virginia, helped to found a network of cities united through biophilia.

Today, the Project's partner cities stretch from Portland to Singapore, Oslo to Wellington, New Zealand -- each pledging to cultivate an urban nature-loving ethos among their populace.

We caught up with Beatley on Tuesday, the day after his keynote address at Portland’s 12th Annual Urban Ecology and Conservation Symposium, to learn more about what makes biophilia a belief, a feeling, and just maybe, the start of a new international language.

The Intertwine Alliance: What is biophilia?

The Intertwine Alliance: What is biophilia?

Tim Beatley: Biophilia is the belief that we have this hard-wired need for nature in our life. When we experience nature we have a whole host of positive reactions that to me demonstrate the premise of biophilia. Stephen Kellert talks about it like a muscle that we need to exercise, reinforce in our daily activities.

The biophilic city is the next step: a city that puts connection to nature at the center of its planning and policy.

I've been working on this one way or another for over 30 years, in habitat conservation, resilient cities, etc. But the idea of biophilia is relatively new. I was here in Portland in January 2012 to give a talk, and had a conversation with Linda Dobson and Mike Houck; that was the beginning of the Biophilic Cities Project.

How did you arrive at the term “biophilia”?

TB: When I first started using the term, it grew out of biophilic design. But I'm more of a policy planner and writer. My engineering friends use the term “biophilic” to refer to green elements added to the design of a building. So I'm extending it to the larger city, and in turn trying to reach the larger professional community.

Why “biophilia” and not “green infrastructure”?

Why “biophilia” and not “green infrastructure”?

TB: A lot of people like the term “green infrastructure,” maybe because it puts investments in nature on par with transportation, gray infrastructure, etc. But to me it's not enough. "Biophilia" emphasizes the innate emotional need we have for nature. Whereas “green infrastructure” is unfeeling, almost technocratic. Biophilia's affect is one of recognition of a deep biological need.

When I launched my book back in 2011, I got funny reactions to the term. People thought biophilia sounded like a disease. Now there's a feeling of “aha.”

Who are you trying to reach with this concept?

TB: So there's a professional audience, a lay audience – individuals out there in the citizenry who are interested in leading a healthier life – and a leadership community, mayors and planners, who can be reached by the research. Planners are increasingly recognizing the value of the terminology.

What is the role of coalitions like The Intertwine Alliance in promoting biophilia?

TB: I talked about Houston Wilderness, Chicago Wilderness. There are a lot of examples here and across the world where groups come together with a common view. When you've got fifty, one hundred, two hundred groups behind a biophilic agenda, that's tremendous power.

There's a vision, and then there are a whole variety of possible implementations. I think the vision, establishing the premise, is almost more important than the specific implementation.

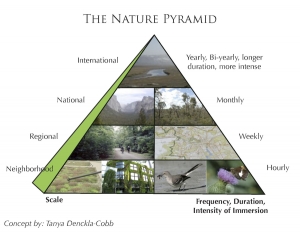

At the UERC Symposium, you talked about establishing a “Nature Pyramid” with recommended daily doses of nature. How do get your daily dose?

At the UERC Symposium, you talked about establishing a “Nature Pyramid” with recommended daily doses of nature. How do get your daily dose?

TB: Well, so I live in a little city in Virginia called Charlottesville. But for a little city we've done bold things. We have a major stream restoration project called Meadow Creek that is coordinated by the city and the Nature Conservancy. The project is about a mile-and-a-half long and it's just spectacular. And, it also goes back to your question of the power of coalitions.

In terms of connection with nature, this is the type of investment -- in a restoration project -- where the idea of a biophilic city comes in. You've got to create a city in which nature is embedded. Meadow Creek is a two-minute walk from my front door, and we go just about everyday.

The real power of an ecosystem services framework is its ability to bolster

The real power of an ecosystem services framework is its ability to bolster  Things are different here in The Intertwine, where this kind of thinking is

Things are different here in The Intertwine, where this kind of thinking is  Which brings me to one last word: Synergy. My online Google dictionary

Which brings me to one last word: Synergy. My online Google dictionary  As a program officer for the

As a program officer for the

Meanwhile,

Meanwhile,  As we reshaped Metro’s publication, we asked our audience for help. They responded, loud and clear: Survey participants most valued easy-to-find information, with quality storytelling and photography a close second. They clamored for field guides that allow them to explore on their own time. Trails, restoration, walking, biking, natural gardening and other sustainable living tools also ranked high.

As we reshaped Metro’s publication, we asked our audience for help. They responded, loud and clear: Survey participants most valued easy-to-find information, with quality storytelling and photography a close second. They clamored for field guides that allow them to explore on their own time. Trails, restoration, walking, biking, natural gardening and other sustainable living tools also ranked high. As Metro’s nature communications coordinator, Laura Oppenheimer engages people in regional parks, trails and natural areas. Transforming Metro’s magazine brought her back to her roots as a journalist. Laura lives in Southeast Portland with her husband and two curious children.

As Metro’s nature communications coordinator, Laura Oppenheimer engages people in regional parks, trails and natural areas. Transforming Metro’s magazine brought her back to her roots as a journalist. Laura lives in Southeast Portland with her husband and two curious children. The

The

2) Restoring habitat in the heart of the city. We can do this today. Even small nodes of

2) Restoring habitat in the heart of the city. We can do this today. Even small nodes of

Travis Williams is Executive Director and Riverkeeper for

Travis Williams is Executive Director and Riverkeeper for  With proper equipment, winching a few black walnut logs out of a Southeast Portland backyard should take 30 minutes. It took my buddy Daniel and I, new to urban timber harvesting, upwards of 11 hours. Or then there was the time a hidden chunk of metal buried in three deodar cedar logs -- removed from a landscape project near Grant High School -- chewed up another friend’s sawmill blades.

With proper equipment, winching a few black walnut logs out of a Southeast Portland backyard should take 30 minutes. It took my buddy Daniel and I, new to urban timber harvesting, upwards of 11 hours. Or then there was the time a hidden chunk of metal buried in three deodar cedar logs -- removed from a landscape project near Grant High School -- chewed up another friend’s sawmill blades.

David Barmon co-owns

David Barmon co-owns  Adieu, 2013. You've been a good year for The Intertwine. Our coalition has grown, and with it, our collective power to achieve good things.

Adieu, 2013. You've been a good year for The Intertwine. Our coalition has grown, and with it, our collective power to achieve good things.

Ramona DeNies, Writer & Editor for The Intertwine Alliance, wrote this post with help from the

Ramona DeNies, Writer & Editor for The Intertwine Alliance, wrote this post with help from the

Through her work, Jean Akers, both landscape architect and certified planner, promotes conservation and sustainable outdoor recreation for park and trail systems in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. She also serves on the Board of the

Through her work, Jean Akers, both landscape architect and certified planner, promotes conservation and sustainable outdoor recreation for park and trail systems in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. She also serves on the Board of the  “I have seriously moved to the burbs. What will become of me?” This was among my first thoughts driving to my new home in Happy Valley in 2011, with hubby, kids and dog in tow.

“I have seriously moved to the burbs. What will become of me?” This was among my first thoughts driving to my new home in Happy Valley in 2011, with hubby, kids and dog in tow.

Renee Myers, Executive Director of the

Renee Myers, Executive Director of the  “Yeah, but who is going to keep this going when you’re dead?”

“Yeah, but who is going to keep this going when you’re dead?” After all, legacy hits at the core of why we conservationists do what we do. Whether we get paid for our work, or volunteer our time, our shared motive is to leave something worth protecting over centuries. While fundraising, politics, and community organizing are certainly important, the ultimate key to our success (or failure) is whether we can spark a fire in the bellies of our children to serve as stewards of the land after we’re gone.

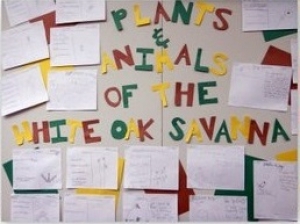

After all, legacy hits at the core of why we conservationists do what we do. Whether we get paid for our work, or volunteer our time, our shared motive is to leave something worth protecting over centuries. While fundraising, politics, and community organizing are certainly important, the ultimate key to our success (or failure) is whether we can spark a fire in the bellies of our children to serve as stewards of the land after we’re gone. Today, only two percent remains of the 600,000 acres of

Today, only two percent remains of the 600,000 acres of  And lately, they show us how it’s done. Young students at a local after-school

And lately, they show us how it’s done. Young students at a local after-school  So when a young person serving me at the local pizza spot remembers me working with their class two years ago, to plant a thousand blue camas bulbs, I feel reassured that we gray-haired conservationists will be leaving

So when a young person serving me at the local pizza spot remembers me working with their class two years ago, to plant a thousand blue camas bulbs, I feel reassured that we gray-haired conservationists will be leaving

Kurt Beil, ND, LAc, MPH is a holistic physician and researcher at the

Kurt Beil, ND, LAc, MPH is a holistic physician and researcher at the