Silt vs. Soil

Protecting The Intertwine from the evils of erosion

Scott Gall

“A nation that destroys its soil destroys itself.”

“A nation that destroys its soil destroys itself.”

Franklin Roosevelt wrote those words in a letter to all State Governors in support of the act that created Soil & Water Conservation Districts. That was in 1937 and the nation had just passed a series of laws in response to the devastation caused by the Dust Bowl.

Eighty years later, our understanding of the strength and fragility of native soils is greater than ever. Yet erosion will always be a concern -- even here in The Intertwine.

We know that soil erosion occurs when soil particles detach and move around, usually caused by water, wind, gravity and even ice. And we know that erosion can be devastating, both to the natural landscape and to our homes -- compromising foundations, clogging drains, and dislodging whole gardens.

We know that soil erosion occurs when soil particles detach and move around, usually caused by water, wind, gravity and even ice. And we know that erosion can be devastating, both to the natural landscape and to our homes -- compromising foundations, clogging drains, and dislodging whole gardens.

Lastly, we know that our native soil is precious. It takes about 200 years to form one inch of soil!

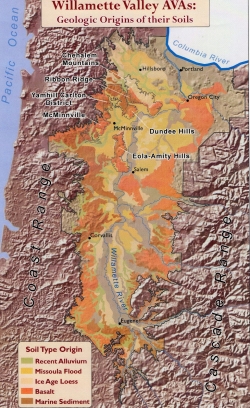

But you might be wondering, why is erosion a concern here in the fertile Willamette Valley -- sheltered from Gorge winds, hundreds of miles from from drought-stricken California and half a continent from the locus of the Dust Bowl?

One word: silt.

In Portland, the most erosive areas are in the West Hills. Most of the soil there was formed during the Ice Age following events known as the Missoula Floods, which would have covered Portland is as much as 400 feet of water carrying soil and rocks from distant parts of Washington, Idaho and Montana. After the flood water receded, it left mostly sand and silt, which was then carried by wind up into the West Hills.

Silt causes two main problems.

First, silt is the most erosive type of soil, its fine particles easily carried by wind and unlikely to bond chemically, as do small clay particles. This windblown matter, called loess, dominates the soil of the West Hills.

Second, silt can bury preexisting soil, forming a layer that engineers call a slip plane. Rain and irrigation water seeps through the newer soil, but stops at the slip plane, blocked by less permeable older soil.

With enough water and not enough support (from cover, roots, or other erosion control measures) a slope can fail. These types of landslides have occurred for thousands of years. More recently and close to home, we've seen the media pictures of homes sliding into each other in the West Hills.

With enough water and not enough support (from cover, roots, or other erosion control measures) a slope can fail. These types of landslides have occurred for thousands of years. More recently and close to home, we've seen the media pictures of homes sliding into each other in the West Hills.

So, how do we combat loess and the slip plane factor?

One of the best ways to stabilize both slope and soil is to plant grass, shrubs and trees. Here are just a few reasons why vegetation is a soil savior's best friend:

Root systems, and the fibrous mycorrhiza fungus that attach to them, literally hold the soil in place.

Root systems, and the fibrous mycorrhiza fungus that attach to them, literally hold the soil in place.- Roots can also create holes, known as pores, which allow water to seep into the ground, rather than pond on the surface and wash soil away.

- Plants pull the water they need from the ground, they help prevent soil in steep areas from getting too saturated and heavy.

- Plant roots also pump organic matter, formed from the breakdown and composting of living material, deep into the soil -- forming a "glue" that holds soil together. This organic matter contributes to a virtuous cycle, holding water deep within the soil (more efficiently than mulch, compost and other amendments, I might add) and providing nutrients for crops, trees and ornamentals in your garden.

So now that you know erosion could be just a rainstorm away, take a look around your home. Does your native soil need more cover? We're here to help.

Contact West Multnomah Soil and Water Conservation District for more information on soil, erosion, or other conservation practices. Or check out WMSWCD's Soil School -- an April 5th course intended for gardeners and beginning small farmers. Held at Lewis & Clark College, you’ll learn what’s in your soil, how to test and analyze your own soil sample, and determine the best way to amend your soil for your growing needs.

Since 2008, Scott Gall has served as a Rural Conservationist with the

Since 2008, Scott Gall has served as a Rural Conservationist with the

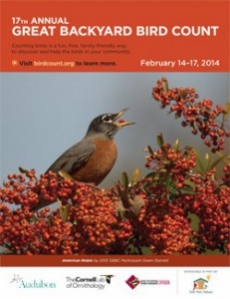

If you’re new to citizen science or birding, this is a great way to get your feet wet: You can spend as little as 15 minutes identifying and counting birds. And, it’s no problem if you are a beginning birder and don’t recognize all the birds you see. When you submit data to the Great Backyard Bird Count website, just say that you weren’t able to identify certain birds.

If you’re new to citizen science or birding, this is a great way to get your feet wet: You can spend as little as 15 minutes identifying and counting birds. And, it’s no problem if you are a beginning birder and don’t recognize all the birds you see. When you submit data to the Great Backyard Bird Count website, just say that you weren’t able to identify certain birds. The National Audubon Society and Cornell Lab of Ornithology combine the data from this count with information from other citizen science projects, including the

The National Audubon Society and Cornell Lab of Ornithology combine the data from this count with information from other citizen science projects, including the  Participation in the Great Backyard Bird Count has increased steadily in Portland over the last few years.

Participation in the Great Backyard Bird Count has increased steadily in Portland over the last few years. Joe Liebezeit is the Avian Conservation Program Manager for the

Joe Liebezeit is the Avian Conservation Program Manager for the  With proper equipment, winching a few black walnut logs out of a Southeast Portland backyard should take 30 minutes. It took my buddy Daniel and I, new to urban timber harvesting, upwards of 11 hours. Or then there was the time a hidden chunk of metal buried in three deodar cedar logs -- removed from a landscape project near Grant High School -- chewed up another friend’s sawmill blades.

With proper equipment, winching a few black walnut logs out of a Southeast Portland backyard should take 30 minutes. It took my buddy Daniel and I, new to urban timber harvesting, upwards of 11 hours. Or then there was the time a hidden chunk of metal buried in three deodar cedar logs -- removed from a landscape project near Grant High School -- chewed up another friend’s sawmill blades.

David Barmon co-owns

David Barmon co-owns  Recently, watching the sun rise at

Recently, watching the sun rise at  As the communications lead for

As the communications lead for

A visit to

A visit to  Every day that I visit

Every day that I visit  Sheri Wantland is a public involvement coordinator for

Sheri Wantland is a public involvement coordinator for  “I have seriously moved to the burbs. What will become of me?” This was among my first thoughts driving to my new home in Happy Valley in 2011, with hubby, kids and dog in tow.

“I have seriously moved to the burbs. What will become of me?” This was among my first thoughts driving to my new home in Happy Valley in 2011, with hubby, kids and dog in tow.

Renee Myers, Executive Director of the

Renee Myers, Executive Director of the  “Yeah, but who is going to keep this going when you’re dead?”

“Yeah, but who is going to keep this going when you’re dead?” After all, legacy hits at the core of why we conservationists do what we do. Whether we get paid for our work, or volunteer our time, our shared motive is to leave something worth protecting over centuries. While fundraising, politics, and community organizing are certainly important, the ultimate key to our success (or failure) is whether we can spark a fire in the bellies of our children to serve as stewards of the land after we’re gone.

After all, legacy hits at the core of why we conservationists do what we do. Whether we get paid for our work, or volunteer our time, our shared motive is to leave something worth protecting over centuries. While fundraising, politics, and community organizing are certainly important, the ultimate key to our success (or failure) is whether we can spark a fire in the bellies of our children to serve as stewards of the land after we’re gone. Today, only two percent remains of the 600,000 acres of

Today, only two percent remains of the 600,000 acres of  And lately, they show us how it’s done. Young students at a local after-school

And lately, they show us how it’s done. Young students at a local after-school  So when a young person serving me at the local pizza spot remembers me working with their class two years ago, to plant a thousand blue camas bulbs, I feel reassured that we gray-haired conservationists will be leaving

So when a young person serving me at the local pizza spot remembers me working with their class two years ago, to plant a thousand blue camas bulbs, I feel reassured that we gray-haired conservationists will be leaving

Yes, you too* can become the Sheriff of Weed Town, particularly in spring -- an excellent time to appreciate the lovely blossoms of such invaders as

Yes, you too* can become the Sheriff of Weed Town, particularly in spring -- an excellent time to appreciate the lovely blossoms of such invaders as  Jennifer Nelson, JD MS, is the Outreach Coordinator for the

Jennifer Nelson, JD MS, is the Outreach Coordinator for the

Last spring, I walked into the exam room of the

Last spring, I walked into the exam room of the  This is a large enough caseload that Audubon can identify problems affecting urban wildlife populations in addition to treating individual animals. My main takeaway from watching these trends unfold in the care center? You need more than good intentions and gut-level reactions to successfully coexist with wildlife in urban settings.

This is a large enough caseload that Audubon can identify problems affecting urban wildlife populations in addition to treating individual animals. My main takeaway from watching these trends unfold in the care center? You need more than good intentions and gut-level reactions to successfully coexist with wildlife in urban settings. A

A  To help local residents navigate the nuances of human-wildlife interactions, Portland Audubon provides an “

To help local residents navigate the nuances of human-wildlife interactions, Portland Audubon provides an “ Birds are drawn into Portland’s urban landscape during migration, where they run the risk of striking into windows around almost every corner. Many diurnal birds migrate at night in order to avoid predators, maximize daylight foraging hours, and make use of celestial navigation cues. Bright lights lure these nighttime migrants into cities and confuse them by obscuring their navigational aids, which makes it difficult for the birds to find their way back out of a developed area and its maze of glass.

Birds are drawn into Portland’s urban landscape during migration, where they run the risk of striking into windows around almost every corner. Many diurnal birds migrate at night in order to avoid predators, maximize daylight foraging hours, and make use of celestial navigation cues. Bright lights lure these nighttime migrants into cities and confuse them by obscuring their navigational aids, which makes it difficult for the birds to find their way back out of a developed area and its maze of glass. Tinsley started at

Tinsley started at  After spotting a certain mammal enjoying a trout dinner at Reed College, my husband and I shared the news with family and friends: “We have otters for neighbors!” To us, what’s really incredible about this is that we live in the middle of the city (click

After spotting a certain mammal enjoying a trout dinner at Reed College, my husband and I shared the news with family and friends: “We have otters for neighbors!” To us, what’s really incredible about this is that we live in the middle of the city (click  Peregrine Edison-Lahm works for

Peregrine Edison-Lahm works for

Lori Hennings is a senior natural resource scientist for

Lori Hennings is a senior natural resource scientist for