Expanding The Intertwine’s connected system of trails will create many economic, public health and cultural benefits

The Intertwine Alliance vision of a network of regional trails and on-street routes is becoming the backbone of a valued transportation and recreation system allowing people to spend less money, lose a few pounds, and live with a lighter footprint.

The Intertwine includes about 300 miles of bike, pedestrian, and water trails. Not only are these trails fun to use for recreation or exercise, they are also very practical. Nearly 12 percent of people use these trails and other paths to get to work every day in the city, and 18 percent of all trips in the region are made by biking or walking. In fact, Portland has more cycling than any other city in the U.S. – accounting for 6 percent of all transportation modes.

The Intertwine includes about 300 miles of bike, pedestrian, and water trails. Not only are these trails fun to use for recreation or exercise, they are also very practical. Nearly 12 percent of people use these trails and other paths to get to work every day in the city, and 18 percent of all trips in the region are made by biking or walking. In fact, Portland has more cycling than any other city in the U.S. – accounting for 6 percent of all transportation modes.

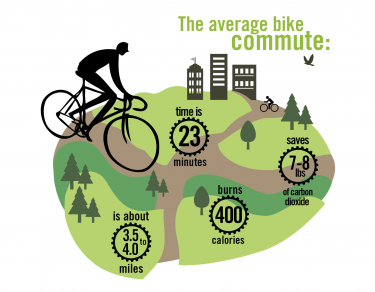

Using alternative modes of transportation is beneficial to our health, as it gets us outside and moving, keeping us on average 10 pounds slimmer. Walking and biking are associated with higher cardiovascular fitness, lower mortality rates, decreased cancer risk, and decreased risk of overweight and obesity. Green exercise can also reduce stress, and build strength, muscle tone and stamina.

Active transportation benefits air quality, since transportation in general is responsible for 25 percent of greenhouse gas emissions throughout The Intertwine. With each mile pedaled or walked instead of driven, nearly one pound of carbon dioxide is saved.

Regional leaders hope to continue increasing numbers of bikers and walkers. The City of Portland Bureau of Transportation has reported that 60 percent of people in the region are interested in cycling, but most also indicated safety as a number one concern. Studies show that people are more likely to use the trails if they are safe and complete. However, with current funding, it will take the region approximately 150 years to complete the regional trail network. Regional trails are only 44 percent complete currently, and only 3 percent of federal/state funding is dedicated to pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure. This means there are still huge gaps in the planned network, which could make traveling more dangerous and less accessible, a big deterrent for getting people to cycle/walk more.

"Our big thing is that we would love to see all the trails connected in Oregon, so that you have trails that could literally get you from Banks to Nob Hill with a beautiful trail all connected, or multiple trails connected. That would be fantastic. That would help me sell Oregon just so much more. " - Don Cooper, Talent Advisor and Executive Search Recruiter, Intel Corporation

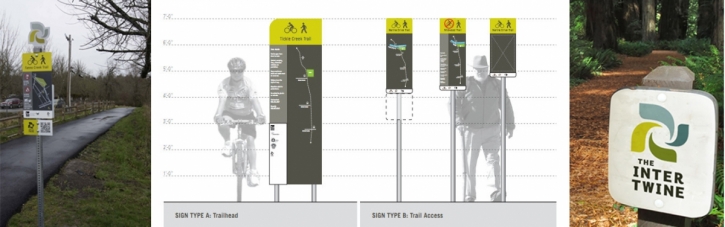

The Intertwine Alliance and Metro are working on establishing a unified system of signs along all the trails in the region. First posted on the Fanno Creek Trail in Beaverton, the Intertwine signs help people commute to work and school, run errands and recreate, linking these trails to the surrounding communities. As this network spreads out to every corner of the region, the use of these trails is dramatically increasing. Metro’s traffic studies suggest that over 2,100,000 trips were taken in 2011 on Portland’s Vera Katz Eastbank Esplanade, another 1,300,000 trips on the South Waterfront Trail, and 410,000 trips on Vancouver’s Salmon Creek Greenway. Studies show that these off-road routes, away from cars, are friendlier to newer users and encourage a broader group of people to try riding a bike or taking a walk.

Metro recently published the Regional Active Transportation Plan, a roadmap to increase bicycling, walking, and public transit in the region and support healthy active living and equity. Its ultimate goal is to triple current mode usage by encouraging completion of the network, and by increasing safety, comfort, and access.

The plan stresses multiple times the low amount of transportation funding that goes toward active transportation, which is 3 percent even though 18 percent of all trips use active transportation. The plan identifies gaps in the network, as well as identifies areas of limited access. Using the 2011 Oregon Household Activity Survey, the plan concluded that lower-income households, people with disabilities, young people and people of color use active transportation more than other populations. The plan encourages trail development in areas where these populations exist in order to make bicycling easier and more comfortable for the people already using these modes.

With population in Portland on the rise, it is important to think of the traffic implications this will have. It will become even more important to get people out of their cars and using alternative modes of transportation, for the health of the region, the people and the environment.

“Analysis conducted by the City of Portland … estimates that if its 25% bicycling mode share target is not reached and bicycling levels remain the same, the city will need the equivalent of 18 more Powell Boulevards to accommodate the increase in auto traffic generated by Portland residents alone.” - Active Transportation Plan, page 140

Metro has also developed a bike model in collaboration with Portland State University, the first of its kind in the U.S. The bike model uses data gathered by cyclists and GPS trackers that observe the cyclists’ route choices. With this data, the bike model can estimate how many cyclists would use a new lane or trail. This bike model has been used to make the case for bike infrastructure not yet built.

One example is Foster Road. According to the bike model, ridership would increase by 59 percent if a bike lane was put in. With a tool like this, we are able to see how each new trail segment or bike lane will increase riders and also where it makes the most sense to target our efforts currently.

Our regional trail network is also being designed to seamlessly integrate into the streets in our neighborhoods and link to public transportation. The Intertwine Alliance joins trail planners like Metro, in coordination with local transportation departments, to help connect city streets directly to these new trails.

Many cities in our region recognize the creation of these active transportation routes as opportunities to further upgrade the streets, including storm water filtration and other environmental improvements that benefit the surrounding neighborhood. Such green infrastructure has substantial, measurable economic benefits, and these investments are relatively cheap. The Active Transportation Plan estimates that the entire bike network has been constructed for about $60 million, which is the approximate cost of one freeway interchange (page 38).

See annotated bibliography of research referenced.

Read more about The Intertwine's active transportation work.

A big thank you to Intertwine Alliance researcher Lyndsey Boyle of Portland State University for compiling this report.