And what should I do with the turtle now that I’ve picked it up and brought it home?

And what should I do with the turtle now that I’ve picked it up and brought it home?

I’m so glad you called!

How can I create habitat for native turtles? I know Oregon’s turtles are in trouble, and I want to help them.

Thank you for asking!

I have turtles on my project site. How can I plan and implement the project without harming them?

I wish more people asked this question!

These are just a few of the turtle-related questions I respond to as the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s conservation biologist for the west side of the state. My charge is non-game wildlife, meaning species that cannot be hunted or harvested. That’s a lot of species! Eighty-eight percent of them, to be exact.

I get asked a lot of wildlife questions, and sometimes people — usually students, when I come to their classrooms to talk about bats, frogs and other wild critters — ask, “What is your favorite species?” A challenging question for a wildlife biologist, but it doesn’t take long to mentally form my Top 10 List. Making the cut are Oregon’s two native turtle species, the western pond turtle and the western painted turtle.

Western pond and western painted turtles are amazing creatures! They spend several months during the winter at the bottom of wetlands, ponds and other water bodies, not eating or even coming up for air. Some turtles spend a lot of time on land, too – up to 10 months! – not eating, as they need to be in water to swallow food.

Western pond and western painted turtles are amazing creatures! They spend several months during the winter at the bottom of wetlands, ponds and other water bodies, not eating or even coming up for air. Some turtles spend a lot of time on land, too – up to 10 months! – not eating, as they need to be in water to swallow food.

They are long-lived, social and curious creatures with strong navigational instincts. When hatchling turtles emerge from their nest chambers in the ground (usually about 6 to 8 inches down), they somehow key into the nearest water source and start their journey of survival. I say nearby, but some female turtles nest over 1,000 feet away from their aquatic habitats. Although turtles do use rivers, sloughs and other waterways to move and disperse, western pond and painted turtles are quite capable of, and do make, long overland treks.

In addition to some pretty fascinating behaviors and habits, our native turtles are also quite beautiful. The pond turtle is olive brown and more uniform in color, while the western painted turtle has bright yellow, orange or red lines on its head, neck and legs. The bottom shell (a.k.a. plastron) of the western painted turtle is spectacular with its unique red-and-black pattern. The western pond turtle has a creamy yellow plastron, often with dark staining.

Both turtle species have experienced significant population declines, and continue to be highly vulnerable to habitat loss and other anthropogenic (human-caused) impacts. As such, they are classified as “Critical” on Oregon’s Sensitive Species List, are “protected non-game wildlife” (OAR 635-044) and cannot be killed, and are priority species in the Oregon Conservation Strategy.

Here in The Intertwine, Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area and the Columbia slough are significant habitats for western painted turtles, with some of the region’s largest known populations. As for western pond turtles, it unfortunately appears that hardly any remain in the Portland area, though some are still hanging on in the Tualatin River basin of Washington County, and a few others have been reported in Clackamas County. You can help by reporting all turtle sightings — especially of western pond turtles, which are under endangered-species status review by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — to www.oregonturtles.com.

Here in The Intertwine, Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area and the Columbia slough are significant habitats for western painted turtles, with some of the region’s largest known populations. As for western pond turtles, it unfortunately appears that hardly any remain in the Portland area, though some are still hanging on in the Tualatin River basin of Washington County, and a few others have been reported in Clackamas County. You can help by reporting all turtle sightings — especially of western pond turtles, which are under endangered-species status review by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — to www.oregonturtles.com.

Population trends and large-scale abundance patterns of western pond and western painted turtles are difficult to measure, but declines in both species are believed to be significant given measurable losses in habitat availability (quantity) and habitat function (quality). Habitat loss is due largely due to the conversion of land for human uses, such as urbanization and agriculture. Habitat degradation is due in part to non-native invasive species, such as reed canary grass.

Changes to habitat have occurred throughout Oregon and within the ranges of both turtle species, but are particularly striking in the Willamette Valley. Actions that involve ground disturbance, changes in water level, planting of vegetation, and use of heavy equipment are just a few activities known to negatively affect turtles. Albeit unintentional, these activities can make habitat less suitable for turtles, and even result in direct injury and mortality to turtles present at a project site.

Changes to habitat have occurred throughout Oregon and within the ranges of both turtle species, but are particularly striking in the Willamette Valley. Actions that involve ground disturbance, changes in water level, planting of vegetation, and use of heavy equipment are just a few activities known to negatively affect turtles. Albeit unintentional, these activities can make habitat less suitable for turtles, and even result in direct injury and mortality to turtles present at a project site.

To address a growing demand for proven turtle-helping techniques, ODFW, with input from key turtle conservation partners (collectively known as the Oregon Native Turtle Working Group), recently produced “Guidance for Conserving Oregon’s Native Turtles Including Best Management Practices.” Also referred to as the Turtle BMPs, the document is a compilation of peer-reviewed recommended best methods for creating suitable turtle habitat and for avoiding and minimizing harmful impacts to turtles and their habitats during project implementation, whether it’s culvert replacement, trail construction, dredging, or riparian restoration.

The document also includes an overview of turtle ecology, describes Oregon’s most common non-native invasive turtle species (the red-eared slider and the common snapping turtle), and methods for determining if turtles are present at a particular location or project site. Recommended turtle-habitat assessment tools, survey protocols and data forms are provided, as are recommended plant lists for turtle aquatic and upland habitats.

The guide includes information on various turtle-related topics (e.g., beavers and turtles, page 64, and chemical contaminants and turtles, page 65), photos of suitable turtle habitat, and sidebars with pithy but succinct answers to common turtle-related questions: “What is aestivation?” (page 16) and “What do turtles eat?” (page 30).

The guide includes information on various turtle-related topics (e.g., beavers and turtles, page 64, and chemical contaminants and turtles, page 65), photos of suitable turtle habitat, and sidebars with pithy but succinct answers to common turtle-related questions: “What is aestivation?” (page 16) and “What do turtles eat?” (page 30).

Which brings me back to the turtle found crossing a road. For a more complete answer see page 63, but in a nutshell, turtles may need to cross roads to get where they want to go. Suitable upland habitats are often disconnected from aquatic habitats by roads, railways, trails or a combination of the three.

While turtles can and do cross roads successfully, roads also kill turtles. How many, we do not know. Regardless, the majority of turtles found crossing roads or hit by a moving vehicle are adult females — big girls on a mission to lay their eggs or on their way back to the water after egg-laying. The loss of a sexually mature female turtle is considered a significant loss to an overall turtle population.

So, as long as it is safe for you to do so, it is reasonable to help a native turtle cross a road by moving it a short distance off the road/shoulder area. The key is to keep the turtle pointed in the same direction it was headed. And do not bring the turtle home!

Everyone can play a role in helping to protect and conserve Oregon’s native turtles. Download your free copy of the Turtle BMPs here.

This time of year in the Willamette Valley, we can witness the deep blue blossoms of the lily known in the Native American language Chinuk Wawa as “lakamas,” to scientists as Camassia quamash, and by its English common name, camas (1).

This time of year in the Willamette Valley, we can witness the deep blue blossoms of the lily known in the Native American language Chinuk Wawa as “lakamas,” to scientists as Camassia quamash, and by its English common name, camas (1). Camas flowers are strikingly beautiful, either alone or in large fields where the mass of blue is sometimes mistaken for an azure lake.

Camas flowers are strikingly beautiful, either alone or in large fields where the mass of blue is sometimes mistaken for an azure lake.  Burning purifies the soil, releases nutrients and controls competing (often invasive) vegetation; traditional digging sticks gently till and aerate the soil, and small bulblets are replanted during this practice.

Burning purifies the soil, releases nutrients and controls competing (often invasive) vegetation; traditional digging sticks gently till and aerate the soil, and small bulblets are replanted during this practice.  Native people traditionally cooked camas in large earth ovens or pits. Fire-heated rocks were placed in the oven and then lined with leaves of skunk cabbage, maple or ash. The raw camas bulbs were placed on the leaves, then covered with another layer of leaves and then earth. Upon retrieval from the oven one to three days later, the camas could be eaten immediately, dried for later use, or pressed into cakes.

Native people traditionally cooked camas in large earth ovens or pits. Fire-heated rocks were placed in the oven and then lined with leaves of skunk cabbage, maple or ash. The raw camas bulbs were placed on the leaves, then covered with another layer of leaves and then earth. Upon retrieval from the oven one to three days later, the camas could be eaten immediately, dried for later use, or pressed into cakes. In the highly industrialized Portland Harbor, the Trustee Council is planning restoration projects to bring camas and other culturally significant plants back into the landscape.

In the highly industrialized Portland Harbor, the Trustee Council is planning restoration projects to bring camas and other culturally significant plants back into the landscape.

Michael Karnosh is the Ceded Lands Program Manager for the

Michael Karnosh is the Ceded Lands Program Manager for the  And what should I do with the turtle now that I’ve picked it up and brought it home?

And what should I do with the turtle now that I’ve picked it up and brought it home?  Western pond and western painted turtles are amazing creatures! They spend several months during the winter at the bottom of wetlands, ponds and other water bodies, not eating or even coming up for air. Some turtles spend a lot of time on land, too – up to 10 months! – not eating, as they need to be in water to swallow food.

Western pond and western painted turtles are amazing creatures! They spend several months during the winter at the bottom of wetlands, ponds and other water bodies, not eating or even coming up for air. Some turtles spend a lot of time on land, too – up to 10 months! – not eating, as they need to be in water to swallow food. Here in The Intertwine,

Here in The Intertwine,  Changes to habitat have occurred throughout Oregon and within the ranges of both turtle species, but are particularly striking in the Willamette Valley. Actions that involve ground disturbance, changes in water level, planting of vegetation, and use of heavy equipment are just a few activities known to negatively affect turtles. Albeit unintentional, these activities can make habitat less suitable for turtles, and even result in direct injury and mortality to turtles present at a project site.

Changes to habitat have occurred throughout Oregon and within the ranges of both turtle species, but are particularly striking in the Willamette Valley. Actions that involve ground disturbance, changes in water level, planting of vegetation, and use of heavy equipment are just a few activities known to negatively affect turtles. Albeit unintentional, these activities can make habitat less suitable for turtles, and even result in direct injury and mortality to turtles present at a project site. The guide includes information on various turtle-related topics (e.g., beavers and turtles, page 64, and chemical contaminants and turtles, page 65), photos of suitable turtle habitat, and sidebars with pithy but succinct answers to common turtle-related questions: “What is aestivation?” (page 16) and “What do turtles eat?” (page 30).

The guide includes information on various turtle-related topics (e.g., beavers and turtles, page 64, and chemical contaminants and turtles, page 65), photos of suitable turtle habitat, and sidebars with pithy but succinct answers to common turtle-related questions: “What is aestivation?” (page 16) and “What do turtles eat?” (page 30).  Susan Barnes is the conservation biologist for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s West Region. Her focus is conservation of non-game wildlife and their habitats, including those highlighted in the Oregon Conservation Strategy. Her work includes habitat assessment, impact analysis and mitigation planning, and wildlife policy. She never bores of the sometimes bizarre wildlife-related questions she gets from the public!

Susan Barnes is the conservation biologist for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s West Region. Her focus is conservation of non-game wildlife and their habitats, including those highlighted in the Oregon Conservation Strategy. Her work includes habitat assessment, impact analysis and mitigation planning, and wildlife policy. She never bores of the sometimes bizarre wildlife-related questions she gets from the public!  If you have Oregon white oak trees in your yard, you know they are the last trees to get their spring leaves and the last to lose them in the fall. They make a mess after you’ve raked everything else up, and drop noisy acorns (often squirrel-assisted) on your roof. They sprinkle your yard with mossy little twigs. So why do you keep them?

If you have Oregon white oak trees in your yard, you know they are the last trees to get their spring leaves and the last to lose them in the fall. They make a mess after you’ve raked everything else up, and drop noisy acorns (often squirrel-assisted) on your roof. They sprinkle your yard with mossy little twigs. So why do you keep them? That’s easy. They are simply gorgeous. Just looking at a big, old mushroom-shaped oak makes me feel happy and kind of puts me in my place in the universe. They are also awesome to sit under, swing from and climb.

That’s easy. They are simply gorgeous. Just looking at a big, old mushroom-shaped oak makes me feel happy and kind of puts me in my place in the universe. They are also awesome to sit under, swing from and climb. More than 95 percent of our oak-prairie habitats have disappeared from the Willamette Valley, mostly due to farming, urbanization and fire suppression. Nearly 400 plant species live pretty much only in these habitats, and wildlife species like white-breasted nuthatches and Western gray squirrels have declined in tandem with habitat loss.

More than 95 percent of our oak-prairie habitats have disappeared from the Willamette Valley, mostly due to farming, urbanization and fire suppression. Nearly 400 plant species live pretty much only in these habitats, and wildlife species like white-breasted nuthatches and Western gray squirrels have declined in tandem with habitat loss.  That’s all kind of depressing. What can we do about it? Here's where

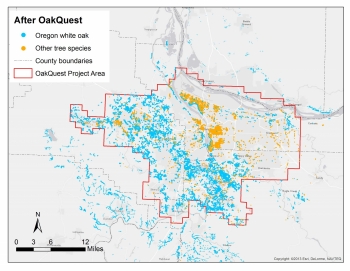

That’s all kind of depressing. What can we do about it? Here's where  Now we are using the information from last year’s field work to refine the oak model. We plan to send out another cadre of OakQuest volunteers this summer, this time with three team leaders hosted by Portland State’s Indigenous Nations Studies program. The team leaders will receive four college credits and, in addition to helping lead the project, they’ll spend numerous days with our partners learning about conservation work and building a professional network.

Now we are using the information from last year’s field work to refine the oak model. We plan to send out another cadre of OakQuest volunteers this summer, this time with three team leaders hosted by Portland State’s Indigenous Nations Studies program. The team leaders will receive four college credits and, in addition to helping lead the project, they’ll spend numerous days with our partners learning about conservation work and building a professional network.  OPWG is initiating a series of “oak-scaping” workshops to help urban and suburban landowners enhance their existing or create new oak-prairie habitat. We’d like to tie in with Audubon Society of Portland/Columbia Land Trust’s

OPWG is initiating a series of “oak-scaping” workshops to help urban and suburban landowners enhance their existing or create new oak-prairie habitat. We’d like to tie in with Audubon Society of Portland/Columbia Land Trust’s  Lori Hennings is a senior natural resource scientist at Metro, the regional government in Portland. She holds a master's degree in wildlife science from Oregon State University. Her work includes conducting bird surveys and working on larger-scale issues including wildlife corridors, oak conservation and regional water quality. Lori loves her job and wishes she could get out in the field more.

Lori Hennings is a senior natural resource scientist at Metro, the regional government in Portland. She holds a master's degree in wildlife science from Oregon State University. Her work includes conducting bird surveys and working on larger-scale issues including wildlife corridors, oak conservation and regional water quality. Lori loves her job and wishes she could get out in the field more. Nob Hill Nature Park is a 6.6-acre oak woodland overlooking the Columbia River and the northern tip of Sauvie Island. Before getting park status from the City of St. Helens, Oregon, in 2008, the land stood neglected and nearly forgotten. It was badly infested with invasive plants. A dead zone full of ivy, holly and blackberry made much of the land impenetrable.

Nob Hill Nature Park is a 6.6-acre oak woodland overlooking the Columbia River and the northern tip of Sauvie Island. Before getting park status from the City of St. Helens, Oregon, in 2008, the land stood neglected and nearly forgotten. It was badly infested with invasive plants. A dead zone full of ivy, holly and blackberry made much of the land impenetrable.  remove vines from trees, a small group of neighbors helped the park's natural environment start to recover. After seeing the seriousness of volunteers, the city granted official park status, and the Friends of Nob Hill have been active stewards there ever since.

remove vines from trees, a small group of neighbors helped the park's natural environment start to recover. After seeing the seriousness of volunteers, the city granted official park status, and the Friends of Nob Hill have been active stewards there ever since. The watershed council generously provides tools and native plants for each work party. Thanks to them, the park received two years of treatment for blackberries, which opened up large new areas. We've replanted there with native plants including willow, spirea, red twig dogwood, vine maple, madrone, cascara, elderberry, yarrow, checkermallow and wild roses. In summer, we water new plantings from a tap provided by the city.

The watershed council generously provides tools and native plants for each work party. Thanks to them, the park received two years of treatment for blackberries, which opened up large new areas. We've replanted there with native plants including willow, spirea, red twig dogwood, vine maple, madrone, cascara, elderberry, yarrow, checkermallow and wild roses. In summer, we water new plantings from a tap provided by the city.  Other native plants that are easy to find at the park include trillium, viburnum ellipticum, Indian plum, oceanspray, Pacific ninebark, mahonia and chokecherry. With all those berries, it's a good place for bird watching. Flocks of cedar waxwings can be seen on serviceberry in spring, and fish-eating osprey from the nearby river can often be heard calling while flying overhead.

Other native plants that are easy to find at the park include trillium, viburnum ellipticum, Indian plum, oceanspray, Pacific ninebark, mahonia and chokecherry. With all those berries, it's a good place for bird watching. Flocks of cedar waxwings can be seen on serviceberry in spring, and fish-eating osprey from the nearby river can often be heard calling while flying overhead. The smothering ivy, for the most part, has been removed from native white oak trees. Future work parties will continue to remove blackberry, as well as pulling more ivy off the ground. Long-range plans could involve work on invasive orchard grass that is spreading rapidly in camas bed areas.

The smothering ivy, for the most part, has been removed from native white oak trees. Future work parties will continue to remove blackberry, as well as pulling more ivy off the ground. Long-range plans could involve work on invasive orchard grass that is spreading rapidly in camas bed areas. The hard work is a long way from done, but clearly the park is in much better ecological shape than it has been for years. Native plants are rebounding. Where else can you see such a profusion of fawn lilies in March or fernleaf biscuitroot in May? With mature oak trees and associated understory, it’s possible to catch a glimpse of what natural life was like here long ago, as well as an excellent view of the river.

The hard work is a long way from done, but clearly the park is in much better ecological shape than it has been for years. Native plants are rebounding. Where else can you see such a profusion of fawn lilies in March or fernleaf biscuitroot in May? With mature oak trees and associated understory, it’s possible to catch a glimpse of what natural life was like here long ago, as well as an excellent view of the river. Caroline Skinner is cofounder and steward of Nob Hill Nature Park, along with her partner Howard Blumenthal. She is also an active member of Friends of Baltimore Woods in the St. Johns neighborhood of Portland, and is coordinator of the group’s quarterly e-newsletter. Active in environmental justice and outdoor restoration projects, she has called Oregon home since 1978 and currently lives in North Portland.

Caroline Skinner is cofounder and steward of Nob Hill Nature Park, along with her partner Howard Blumenthal. She is also an active member of Friends of Baltimore Woods in the St. Johns neighborhood of Portland, and is coordinator of the group’s quarterly e-newsletter. Active in environmental justice and outdoor restoration projects, she has called Oregon home since 1978 and currently lives in North Portland.

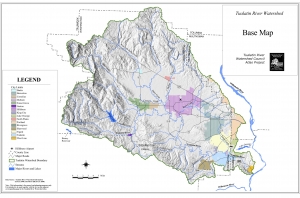

This shallow gradient creates a wide floodplain that has attracted humans and wildlife since the last Ice Age flood inundated the valley. Over half a million people now call the Tualatin Valley home. It is forested and farmed, homesteaded and housing developed, citified and industrialized. Yet, if you know where to look, you can still find a sense of place that might have been experienced by the native Atfalati, the area’s first residents. And, it may well be the birds that help you find it.

This shallow gradient creates a wide floodplain that has attracted humans and wildlife since the last Ice Age flood inundated the valley. Over half a million people now call the Tualatin Valley home. It is forested and farmed, homesteaded and housing developed, citified and industrialized. Yet, if you know where to look, you can still find a sense of place that might have been experienced by the native Atfalati, the area’s first residents. And, it may well be the birds that help you find it. Jackson Bottom Wetlands Preserve is owned and managed by the City of Hillsboro Parks & Recreation Department. Its 635 acres are part of almost 3,000 acres of undeveloped riparian, wetland and agricultural habitat along the river. During the dry season you can explore the four miles of walking trails from dawn to dusk; the river overflows in winter and floods much of the preserve. All year round, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., volunteers welcome you to the education building with a nature store, classroom, office space, pollinator garden, demonstration garden and natural history displays — including an actual bald eagle nest.

Jackson Bottom Wetlands Preserve is owned and managed by the City of Hillsboro Parks & Recreation Department. Its 635 acres are part of almost 3,000 acres of undeveloped riparian, wetland and agricultural habitat along the river. During the dry season you can explore the four miles of walking trails from dawn to dusk; the river overflows in winter and floods much of the preserve. All year round, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., volunteers welcome you to the education building with a nature store, classroom, office space, pollinator garden, demonstration garden and natural history displays — including an actual bald eagle nest. Educational programming serves over 5,000 visiting school children, and another 1,000 are reached by traveling programs. Community and adult education programming is increasing with the recent addition of a Nature Program Supervisor to the Jackson Bottom staff.

Educational programming serves over 5,000 visiting school children, and another 1,000 are reached by traveling programs. Community and adult education programming is increasing with the recent addition of a Nature Program Supervisor to the Jackson Bottom staff.

Metro wildlife monitoring volunteers are amazing people.

Metro wildlife monitoring volunteers are amazing people. In the past decade, Metro has initiated several restoration projects in floodplains, including one at Multnomah Channel Marsh near Forest Park.

In the past decade, Metro has initiated several restoration projects in floodplains, including one at Multnomah Channel Marsh near Forest Park. Over the past decade, red-legged frogs and other amphibians expanded into most of the new wetlands and now breed at many locations. One year we counted over 370 frog egg masses. Since each egg mass can hold as many as 850 eggs, that’s a lot of frogs! Of course, not all of the eggs develop into adult frogs (native predators need food, too).

Over the past decade, red-legged frogs and other amphibians expanded into most of the new wetlands and now breed at many locations. One year we counted over 370 frog egg masses. Since each egg mass can hold as many as 850 eggs, that’s a lot of frogs! Of course, not all of the eggs develop into adult frogs (native predators need food, too). Over the past 12 years, we have monitored over 27 natural areas for amphibians – all sites that were either undergoing or about to undergo restoration. These natural areas are often located next to corporate parks, industrial areas and residential neighborhoods.

Over the past 12 years, we have monitored over 27 natural areas for amphibians – all sites that were either undergoing or about to undergo restoration. These natural areas are often located next to corporate parks, industrial areas and residential neighborhoods.  Katy Weil has worked in wildlife conservation for 32 years. She currently works at Metro in the Natural Areas Program, which focuses upon the restoration of wetlands, uplands and river habitats. Katy has a background in wildlife biology, particularly wildlife field study. Her background as a Pacific Northwest flight instructor allows her a bird’s eye view of the region’s greenspaces. In her spare time, Katy is a happy bird geek, and very thankful that her 8-year-old son shares her love of birds and natural places.

Katy Weil has worked in wildlife conservation for 32 years. She currently works at Metro in the Natural Areas Program, which focuses upon the restoration of wetlands, uplands and river habitats. Katy has a background in wildlife biology, particularly wildlife field study. Her background as a Pacific Northwest flight instructor allows her a bird’s eye view of the region’s greenspaces. In her spare time, Katy is a happy bird geek, and very thankful that her 8-year-old son shares her love of birds and natural places. This spring, I followed a pair of red-tailed hawks, courting in the updrafts, and found their nesting site perched in a narrow ribbon of oak habitat between the noise of industry and traffic.

This spring, I followed a pair of red-tailed hawks, courting in the updrafts, and found their nesting site perched in a narrow ribbon of oak habitat between the noise of industry and traffic. Certain things choose us more than we choose them. That is how it has worked with Friends of Overlook Bluff, stewards of this fringe of oak and madrone trees that hems the east side of the Willamette as the river’s north reach winds toward its confluence with the Columbia.

Certain things choose us more than we choose them. That is how it has worked with Friends of Overlook Bluff, stewards of this fringe of oak and madrone trees that hems the east side of the Willamette as the river’s north reach winds toward its confluence with the Columbia.  We wake up more each year to the significance of our surroundings, and how we might care for it. There is much to steward; Friends of Overlook Bluff inherited a legacy to protect. A Heritage Oregon white oak tree believed to be 150 years old stands alone on an open meadow overlooking the train yards, river, downtown and Forest Park.

We wake up more each year to the significance of our surroundings, and how we might care for it. There is much to steward; Friends of Overlook Bluff inherited a legacy to protect. A Heritage Oregon white oak tree believed to be 150 years old stands alone on an open meadow overlooking the train yards, river, downtown and Forest Park.  From the hawk's perspective, the connection from St. Johns in deep North Portland to Overlook just north of the Fremont Bridge is apparent. Now, the pieces of this quilt are also being assembled on the ground in North Portland -- neighborhood by neighborhood, mile by mile, loop by loop. To volunteer or find out more about us, please visit

From the hawk's perspective, the connection from St. Johns in deep North Portland to Overlook just north of the Fremont Bridge is apparent. Now, the pieces of this quilt are also being assembled on the ground in North Portland -- neighborhood by neighborhood, mile by mile, loop by loop. To volunteer or find out more about us, please visit  Ruth Oclander founded Friends of Overlook Bluff with her neighbors in 2012. She is an acupuncturist and yoga teacher by trade, and enjoys running trails in Forest Park and traveling to far off countries with her husband and young children. Her mother, an Olmsted, can take credit for dragging Ruth into the woods for hikes when she was growing up and letting the grass be overtaken by trees in a backyard that sloped to meet the state forest.

Ruth Oclander founded Friends of Overlook Bluff with her neighbors in 2012. She is an acupuncturist and yoga teacher by trade, and enjoys running trails in Forest Park and traveling to far off countries with her husband and young children. Her mother, an Olmsted, can take credit for dragging Ruth into the woods for hikes when she was growing up and letting the grass be overtaken by trees in a backyard that sloped to meet the state forest. Enjoy urban wildlife? How about geese? If you said yes to the latter, the following fun fact should make you happy: Over the past 20 years, the North American Canada goose population has quadrupled to over 4 million!

Enjoy urban wildlife? How about geese? If you said yes to the latter, the following fun fact should make you happy: Over the past 20 years, the North American Canada goose population has quadrupled to over 4 million!

But how to handle these nuisance neighbors humanely? Time has shown that Canada geese quickly ignore other deterrents such as swans, fake coyotes, flashing lights, noisemakers, and pet dogs.

But how to handle these nuisance neighbors humanely? Time has shown that Canada geese quickly ignore other deterrents such as swans, fake coyotes, flashing lights, noisemakers, and pet dogs.

Liz Clune is an Associate Account Manager & Dog Trainer at

Liz Clune is an Associate Account Manager & Dog Trainer at

Catherine Mushel, an Arbor Month volunteer with the City of Portland, has served on the City’s

Catherine Mushel, an Arbor Month volunteer with the City of Portland, has served on the City’s  Pest control -- is it a necessity or an environmental hornet's nest? If you are like most people I meet, you don’t want sugar ants overrunning your pantry or molehills pock-marking your yard. But you probably also mistrust the chemicals and high costs that can go with the trade.

Pest control -- is it a necessity or an environmental hornet's nest? If you are like most people I meet, you don’t want sugar ants overrunning your pantry or molehills pock-marking your yard. But you probably also mistrust the chemicals and high costs that can go with the trade. Two weeks ago, I attended

Two weeks ago, I attended  An example of the direction we’re going -- one that’s drawn a lot of attention from folks here -- is the owl box. This nature-based solution came to us through Richard, a teammate who previously worked in R&D for Oregon State University.

An example of the direction we’re going -- one that’s drawn a lot of attention from folks here -- is the owl box. This nature-based solution came to us through Richard, a teammate who previously worked in R&D for Oregon State University. The owl box isn’t for those seeking a quick fix to rodent control. It’s a long-term solution -- one that's effective, affordable, and green. And it’s caught on; we’re installing them in parks, cities, schools, even correctional facilities.

The owl box isn’t for those seeking a quick fix to rodent control. It’s a long-term solution -- one that's effective, affordable, and green. And it’s caught on; we’re installing them in parks, cities, schools, even correctional facilities. Eric Ufer is the Founder of

Eric Ufer is the Founder of