A Twine Wire Feature Story

October 21, 2014 – With November elections just around the corner, voters across The Intertwine are weighing in on issues ranging from GMO labeling to gun control.

It’s also here at the ballot box where we decide the future of our parks, trails, and natural areas. Across our four-county region, parks districts and departments routinely contend with shrinking budgets, expiring bonds, and shifting politics.

It’s also here at the ballot box where we decide the future of our parks, trails, and natural areas. Across our four-county region, parks districts and departments routinely contend with shrinking budgets, expiring bonds, and shifting politics.

When big change is needed – redistricting, large acquisitions, major maintenance – voters are asked to step in.

Sometimes, we support that change, as with Metro’s natural areas maintenance levy, passed last year with 54 percent approval. Sometimes, we’re hard to convince; in 2012, voters in Vancouver rejected the proposed formation of a metropolitan parks district with dedicated funding.

We know that one-off conservation campaigns take an excess of time, capital, and energy – resources we quickly muster across our 32 jurisdictions that deplete just as fast after Election Day.

The Intertwine Alliance was created in part to sustain the momentum of these campaigns and achieve even bigger change for our urban nature. Now just over three years old, The Intertwine Alliance, with its 125-plus partners, represents a formidable concentration of political will. How shall we focus this park-changing power?

The Intertwine Alliance was created in part to sustain the momentum of these campaigns and achieve even bigger change for our urban nature. Now just over three years old, The Intertwine Alliance, with its 125-plus partners, represents a formidable concentration of political will. How shall we focus this park-changing power?

To launch this big-landscape conversation, we look to our recent past, our present – where voters will soon decide significant actions in North Clackamas and Portland – and our near future, which will be written, we hope, by partners like you.

THE PAST: Brushing up on Intertwine Political History

Before The Intertwine, there was Esther Short, and John Charles Olmsted.

In 1855, Washington Territory, still thirty years from statehood, received a gift from a remarkable pioneer woman. Just eight years prior, Esther Short, along with her husband and ten children, had homesteaded a wilderness property near Fort Vancouver.

In 1855, Washington Territory, still thirty years from statehood, received a gift from a remarkable pioneer woman. Just eight years prior, Esther Short, along with her husband and ten children, had homesteaded a wilderness property near Fort Vancouver.

But with the young town of Vancouver soon booming all around her, Esther wanted parkland, and donated a four-block plot to create what is now Esther Short Park – the oldest public square in Washington, and one of the West's oldest parks.

Across the Columbia River nearly fifty years later, Portland’s newly formed Parks Department invited a landscape architect from New England to map a more beautiful vision of their rapidly industrializing lumber town.

The ambitious report submitted by John Charles Olmsted in 1903 established an early framework for what, in time, would become The Intertwine.

The ambitious report submitted by John Charles Olmsted in 1903 established an early framework for what, in time, would become The Intertwine.

John Charles’ report set forth 18 best practices in park-planning and recommendations for dozens of key landscapes to preserve, including Mount Talbert, Johnson Creek, and what would later become the 40-Mile Loop.

In many ways, we’re still fulfilling Olmsted's vision – at Rocky Butte, for example, and along Terwilliger Parkway. In other ways, we’ve channeled our growing sense of regional identity into projects far more ambitious than he conceived, as outlined in the Metropolitan Greenspaces Plan, the Portland-Vancouver Bi-State Trails Plan, and The Intertwine’s Regional Conservation Strategy.

BY THE BALLOT: a select Intertwine history

1988 - In Gresham, the passage of a $4.5 million bond sets a local mandate for new parks.

1990 - Gresham voters approve an additional $10 million for parks acquisition.

1992 - Metro Bond Measure 26-1 fails; The Oregonian advises "try again."

1994 - Portland voters pass a 20-year Parks Replacement Bond (now up for renewal).

1995 - Metro voters pass a $135 million bond, with 63 percent approval, for natural area acquisition.

1998 - Portland voters narrowly reject a parks levy.

2002 - Portland voters says yes to Ballot Measure 26-34, a $50 million five-year levy.

2006 - Metro voters pass a second natural areas bond, allowing Metro to purchase a total 13,000 acres of public wilderness.

2010 - Tigard voters approve Measure 34-181, a $17 million bond for parks and open spaces.

2012 - Vancouver voters say no to creating a Greater Vancouver Metropolitan Parks District.

2013 - Metro voters approve a five-year local option levy, providing $10 million a year for natural areas maintenance and education.

2014 - ?

|

Planning is one thing; implementation is another. At current rates of investment, Intertwine Alliance Executive Director Mike Wetter anticipates it will take 190 years to complete the trail network in the Bi-State Plan.

“To me, this number highlights that unless we do something different, achieving our vision is going to take longer than any of us would like,” Wetter says.

“Ballot box success has demonstrated that voters support this topic. Now we need a sustainable funding solution that will allow the vision to be realized.”

By support, Wetter refers to a string of closely-spaced initiatives that date to 1988, when Gresham voters approved a $4.5 million parks acquisition bond measure. A $10 million bond to protect and pay for these lands – a first for the region – followed in 1990.

The next few decades brought more bond measures and levies. In 1995, voters across three counties passed the $135 million Metro Open Spaces Bond (Measure 26-26) with 63 percent approval.

Nine years later, in 2006, Metro area voters passed a land acquisition bond that aimed to improve protections for fish and wildlife as a companion to Metro's Title 13 policies.

In 2008, Beaverton voters approved Measure 34-156, a $100 million bond to develop trails, preserve natural areas, and improve parks and facilities across the Tualatin Hills Parks and Recreation District (THPRD) – itself created by vote in 1955, and now the state’s largest special parks district.

And in Tigard two years later, voters approved Measure 34-181, a $17 million parks and open space bond measure that has helped to facilitate the purchase of parkland at locations including Sumner Creek, the downtown Fields Property, and Bull Mountain.

Of course, along with these many positive steps, Wetter notes, have been Election Day disappointments. Among them, a failed 1992 Metro effort, timed with the adoption of the Metropolitan Greenspaces Plan, a rejected 1998 City of Portland bond measure, and the 2012 dismissal of Vancouver’s proposed parks district.

“We’ve made progress over the last few decades, even in very difficult economic times,” says Wetter. “Now that we’re seeing some economic recovery, it’s easier for voters to respond positively to support our urban wilderness.”

THE PRESENT: New Chapters in Greenspace Action

In just two weeks, Intertwine voters in the City of Portland and Clackamas County will decide on two possible next steps for the evolution of The Intertwine.

Will Portland voters renew a bond to fix up their parks? Thirty miles southeast, will residents in North Clackamas create an independent Parks and Recreation District, loosely modeled after Beaverton’s pioneering THPRD?

Will Portland voters renew a bond to fix up their parks? Thirty miles southeast, will residents in North Clackamas create an independent Parks and Recreation District, loosely modeled after Beaverton’s pioneering THPRD?

Each time, the politics of parks are different. Here’s what two Intertwine communities are currently debating – and why campaign advocates hope once again, they’ll choose to say yes to parks.

Independent living: North Clackamas and Measure 3-451

“North Clackamas residents highly value wildlife habitat and the quality of life that comes from parks,” says Eleanore Hunter, an Oak Grove community activist and chair of the Yes for Parks 3-451 campaign.

“North Clackamas residents highly value wildlife habitat and the quality of life that comes from parks,” says Eleanore Hunter, an Oak Grove community activist and chair of the Yes for Parks 3-451 campaign.

“Our population has grown to 116,000 people, but our parks department has not had a funding increase for 25 years,” Hunter adds. “People have been clear that they want more parks, more natural areas, more programming for seniors and teens. It’s time to invest in our community.”

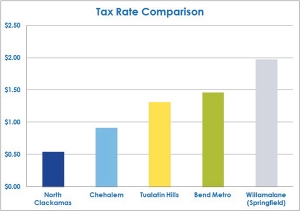

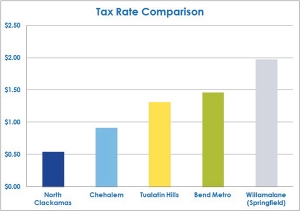

If passed, Ballot Measure 3-451 would entail an annual 89-cent tax rate per $1,000 in assessed property values for homeowners in the 36-square mile district. This funding – still the lowest rate of any parks district in the state, says Hunter – would finance an independent North Clackamas Parks and Recreation District (NCPRD) managed by a new, publicly-elected board.

If passed, Ballot Measure 3-451 would entail an annual 89-cent tax rate per $1,000 in assessed property values for homeowners in the 36-square mile district. This funding – still the lowest rate of any parks district in the state, says Hunter – would finance an independent North Clackamas Parks and Recreation District (NCPRD) managed by a new, publicly-elected board.

“North Clackamas has a great diversity of opinions, but we’ve received tremendous support,” Hunter says. “There are very pragmatic reasons to vote yes for parks: increased property values, recreational opportunities, quality of life, and a third space for communities to grow. Everybody benefits.”

Protect what you have: Portland Parks & Recreation and Measure 26-159

In Portland, another energetic campaign has been raking up support for the city’s underfunded parks maintenance programs through Ballot Measure 26-159, the Parks Replacement Bond.

In Portland, another energetic campaign has been raking up support for the city’s underfunded parks maintenance programs through Ballot Measure 26-159, the Parks Replacement Bond.

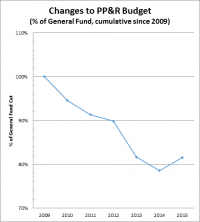

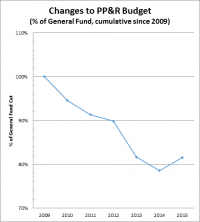

According to Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R), $365 million dollars will be needed over the next decade for major repairs and maintenance, from fixing trails and replacing aging playground structures to refurbishing 12 of the city’s 13 public pools.

But with PP&R’s budget derived entirely from the city’s squeezed general fund, these higher-cost items may never be addressed.

“There’s almost no money set aside for fixing major things, but the needs aren’t visible to the average citizen,” says Nick Hardigg, Executive Director of the nonprofit Portland Parks Foundation. “Only when something people love gets shut down do people realize there's a systemic problem here.”

“There’s almost no money set aside for fixing major things, but the needs aren’t visible to the average citizen,” says Nick Hardigg, Executive Director of the nonprofit Portland Parks Foundation. “Only when something people love gets shut down do people realize there's a systemic problem here.”

Hardigg says the eye-opener for Portland Parks Commissioner Amanda Fritz came this past spring, with the condemning of downtown Couch Park’s deteriorating wooden play structure. Recognizing the lack of funds available to PP&R for urgent repairs, Fritz advocated with City Council to bring Parks Replacement Bond Measure 26-159 to the November ballot.

For Portland voters, the cost of passing Measure 26-159 is literally none: the measure entails no tax rate increase, but rather a continuation of current rates as a twenty-year-old expiring parks bond is renewed.

For Portland voters, the cost of passing Measure 26-159 is literally none: the measure entails no tax rate increase, but rather a continuation of current rates as a twenty-year-old expiring parks bond is renewed.

"The only way we have to bring substantial relief to parks is through ballot measures," Hardigg says. "But when funding comes in unpredictable chunks, it can wreak havoc on maintenance and planning."

THE FUTURE: Large Landscapes take Big Picture Thinking

Squeezed general funds. One-off ballot measures and levies. Revenue dependent on fluctuating property taxes and shifting politics. Without longer term solutions for parks agencies across The Intertwine, voters can expect to see frequent campaigns like Measures 3-451 and 26-159.

“Why bond measures and levies? The answer goes back to state law,” says Heather Nelson Kent, Grants Program Manager for Metro’s Natural Areas Program.

“Why bond measures and levies? The answer goes back to state law,” says Heather Nelson Kent, Grants Program Manager for Metro’s Natural Areas Program.

“Across the nation, sales tax is one of the top sources of funding for programs like ours. Obviously that’s not an option for us here in Oregon,” Kent adds.

So what other tools can we access here in The Intertwine? From establishing independent parks districts and private conservancies, to seeking gas taxes, tax increment financing and urban renewal funds, a wide range of funding tactics have been employed by parks agencies across the nation (and their friends).

By necessity, we have to be that savvy, says former PP&R Director Zari Santner.

“When there are deficits in other general fund spending, parks budgets are looked at, and are often reduced, to fill the gaps,” says Santner. “Parks departments have to be opportunistic.”

But what about even larger landscape thinking? In Clark County, where voters rejected a parks district two years ago, long-time environmental advocate Jean Akers maintains hope that someday a regional collaborative approach might unite the county’s half-dozen parks jurisdictions.

But what about even larger landscape thinking? In Clark County, where voters rejected a parks district two years ago, long-time environmental advocate Jean Akers maintains hope that someday a regional collaborative approach might unite the county’s half-dozen parks jurisdictions.

“We had a blue ribbon committee in 2010, and they all acknowledged that their funding wasn’t stable, that parks were always ready to be cut. But they weren’t ready yet to take up a regional approach. They were in maintenance mode,” Akers says.

“Now that property values have picked up, maybe the pressure is less,” she adds.

Akers isn’t the only conservationist who hopes that the climate for political collaboration, and voter support, is starting to improve.

Intertwine Alliance Board member Don Goldberg, a Senior Project Manager with the Trust for Public Land and veteran of many local conservation campaigns (several here mentioned) says that even with diminishing federal and state funds for public services, Intertwine communities still rally reliably for parks.

Intertwine Alliance Board member Don Goldberg, a Senior Project Manager with the Trust for Public Land and veteran of many local conservation campaigns (several here mentioned) says that even with diminishing federal and state funds for public services, Intertwine communities still rally reliably for parks.

“Every community has a threshold for how much they’re willing to tax themselves. As communities take on more, some that normally wouldn’t blink about funding parks and trails started to question it. They’re overburdened.”

“Having said that,” Goldberg adds, “we’re incredibly fortunate to live in an area that’s highly supportive. The goal is to have all children live within a ten minute walk of a park, trail, or natural area.”

For Intertwine Executive Director Mike Wetter, the rapid growth of The Intertwine Alliance (now 125-plus public, private, and nonprofit partners and counting) is evidence that large landscape thinking – backed by sustainable funding – is more possible now than ever before.

For Intertwine Executive Director Mike Wetter, the rapid growth of The Intertwine Alliance (now 125-plus public, private, and nonprofit partners and counting) is evidence that large landscape thinking – backed by sustainable funding – is more possible now than ever before.

“Over decades, so many have worked to bring the vision of Olmsted and his precursors to life,” Wetter says. “To me, the momentum we’re seeing now means we’re finally ready for big things here in The Intertwine.”

On November 4th, we’ll once again test that momentum, as voters decide what’s next for The Intertwine.

Updated tree regulations took effect January 1, 2015, as part of the City of Portland's efforts to clarify existing code and meet its tree canopy goals. Revisions protect the urban canopy, provide consistency and improve customer service.

Updated tree regulations took effect January 1, 2015, as part of the City of Portland's efforts to clarify existing code and meet its tree canopy goals. Revisions protect the urban canopy, provide consistency and improve customer service.  If you have a tree on your property that is 12 inches or larger in diameter, you will now need a permit to remove it. Planting, pruning, or removing street trees also requires a permit. Planting and pruning permits are free. Removal permits cost $25 and will be available at the City of Portland Development Services Center. Or applications may be mailed with an enclosed check. In many cases, permits will be issued the day of application.

If you have a tree on your property that is 12 inches or larger in diameter, you will now need a permit to remove it. Planting, pruning, or removing street trees also requires a permit. Planting and pruning permits are free. Removal permits cost $25 and will be available at the City of Portland Development Services Center. Or applications may be mailed with an enclosed check. In many cases, permits will be issued the day of application.  In development situations, such as a new home or a substantial exterior alteration, requirements for tree preservation and planting may be triggered. When regulations apply, a portion of the trees on site must be preserved using specific protection methods, and tree canopy density standards must be met through preservation of existing trees and planting new trees. There is an opportunity to pay a fee in lieu of preservation and/or planting.

In development situations, such as a new home or a substantial exterior alteration, requirements for tree preservation and planting may be triggered. When regulations apply, a portion of the trees on site must be preserved using specific protection methods, and tree canopy density standards must be met through preservation of existing trees and planting new trees. There is an opportunity to pay a fee in lieu of preservation and/or planting.

At the spring 2013 Intertwine Alliance summit, we celebrated the 25th anniversary of the greenspaces movement with a retrospective honoring those who have carried the torch for many years. There was a lot of gray hair behind the podium that day, but the “geezers” (their term, not mine!) showed that they have been and still are a force to be reckoned with. The “symbolic message” was that a dedicated corps of hard-working visionaries can powerfully affect the direction of an entire metropolitan region.

At the spring 2013 Intertwine Alliance summit, we celebrated the 25th anniversary of the greenspaces movement with a retrospective honoring those who have carried the torch for many years. There was a lot of gray hair behind the podium that day, but the “geezers” (their term, not mine!) showed that they have been and still are a force to be reckoned with. The “symbolic message” was that a dedicated corps of hard-working visionaries can powerfully affect the direction of an entire metropolitan region.  At this November’s summit, the people standing behind the podium were those who will be leading the next 25 years. We heard from youth leaders emerging from the Audubon Society of Portland’s

At this November’s summit, the people standing behind the podium were those who will be leading the next 25 years. We heard from youth leaders emerging from the Audubon Society of Portland’s

The metro region — with its progressive politics, protected urban growth boundary and rural reserve, commitment to local food, and interest in all things green — provides a great opportunity to test the reinvention of the age-old concept of living close to nature. Imagine our own orange belt (like green) — or food belt, if you will — around the edge of the region providing small adjoining plots of land that families or small cooperative groups can cycle, bus or drive to. Imagine families, community groups or youth leaving their homes for the weekend to learn about soil, the sun, and the seasonal nature of planting and tending food, occasionally foraging in nearby forests or meadows for medicinal plants, roots, berries and the like. Small cabins provide places to gather at the end of a long day, to tell stories about the previous years’ crop success and failures.

The metro region — with its progressive politics, protected urban growth boundary and rural reserve, commitment to local food, and interest in all things green — provides a great opportunity to test the reinvention of the age-old concept of living close to nature. Imagine our own orange belt (like green) — or food belt, if you will — around the edge of the region providing small adjoining plots of land that families or small cooperative groups can cycle, bus or drive to. Imagine families, community groups or youth leaving their homes for the weekend to learn about soil, the sun, and the seasonal nature of planting and tending food, occasionally foraging in nearby forests or meadows for medicinal plants, roots, berries and the like. Small cabins provide places to gather at the end of a long day, to tell stories about the previous years’ crop success and failures.  If all of this sounds far-fetched, just remember the successful European examples, in which people see themselves as not just urban, but also as farmers and nature lovers. This blended and trifold identity will help conversations occur more easily between the environmental, farming, and urban communities who too often see each other as coming from far ends of the spectrum. These three identities combined is how humanity used to see itself, and how we could perceive ourselves again in the future.

If all of this sounds far-fetched, just remember the successful European examples, in which people see themselves as not just urban, but also as farmers and nature lovers. This blended and trifold identity will help conversations occur more easily between the environmental, farming, and urban communities who too often see each other as coming from far ends of the spectrum. These three identities combined is how humanity used to see itself, and how we could perceive ourselves again in the future.  Mark Davison is a

Mark Davison is a  Robin Craig is a Senior Associate and Project Manager at GreenWorks with 20 years of experience in landscape architecture, urban design and planning. She has an expansive background in a variety of design assignments but has focused on strategic, vision, and system planning for the past 9 years. Robin has experience with park master planning, UGB concept plans, greenway systems and more.

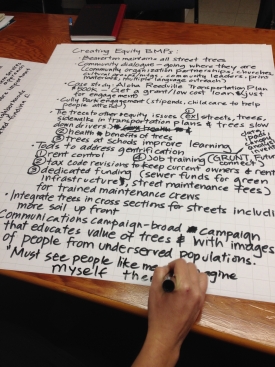

Robin Craig is a Senior Associate and Project Manager at GreenWorks with 20 years of experience in landscape architecture, urban design and planning. She has an expansive background in a variety of design assignments but has focused on strategic, vision, and system planning for the past 9 years. Robin has experience with park master planning, UGB concept plans, greenway systems and more. Big takeaways: Urban tree policy works best when we know what our goals are, when we involve all stakeholders early on, and when we focus on desired outcomes rather than particular and predetermined strategies of how to achieve them.

Big takeaways: Urban tree policy works best when we know what our goals are, when we involve all stakeholders early on, and when we focus on desired outcomes rather than particular and predetermined strategies of how to achieve them. With all these benefits, you would think there would be nothing controversial about protecting our urban forests. But trees can have their down sides, too. While they benefit the entire community, the costs of protecting, maintaining and replacing trees often fall on just a few people — making efforts to regulate them contentious.

With all these benefits, you would think there would be nothing controversial about protecting our urban forests. But trees can have their down sides, too. While they benefit the entire community, the costs of protecting, maintaining and replacing trees often fall on just a few people — making efforts to regulate them contentious. Other conference participants described going through a several-year process of developing a tree code that satisfied one side, only to be torpedoed by the other side at the end of the process — stopping any new urban forestry policy from taking place.

Other conference participants described going through a several-year process of developing a tree code that satisfied one side, only to be torpedoed by the other side at the end of the process — stopping any new urban forestry policy from taking place. Brian Wegener, a Tigard resident for the past 30 years, is the Advocacy & Communications Manager for Tualatin Riverkeepers and serves on the board of Oregon Community Trees. He has worked on policy and demonstration projects promoting the use of urban forestry for stormwater management. He is also allergic to tree pollen.

Brian Wegener, a Tigard resident for the past 30 years, is the Advocacy & Communications Manager for Tualatin Riverkeepers and serves on the board of Oregon Community Trees. He has worked on policy and demonstration projects promoting the use of urban forestry for stormwater management. He is also allergic to tree pollen.  My earliest memory of feeling connected to nature was going to outdoor school in sixth grade. It was a week-long

My earliest memory of feeling connected to nature was going to outdoor school in sixth grade. It was a week-long  A program of the

A program of the

One camp that stands out in my memory is a two-week trip for high schoolers to the San Juans. One day, thousands of dead jellyfish washed ashore. We starting pulling them out of the water with a big stick, amazed at how pretty they were. I had never seen a jellyfish before. Another time, a fox strolled right by our campfire at twilight.

One camp that stands out in my memory is a two-week trip for high schoolers to the San Juans. One day, thousands of dead jellyfish washed ashore. We starting pulling them out of the water with a big stick, amazed at how pretty they were. I had never seen a jellyfish before. Another time, a fox strolled right by our campfire at twilight. Dakota Gaines, the Intertwine Alliance’s first-ever office assistant, is 18 years old and a recent graduate of Gresham’s Centennial High. She’s starting a nursing program at Mt. Hood Community College in the spring. You’ll find her at The Intertwine Alliance office on Tuesdays and Thursdays, skillfully multitasking all we send her way.

Dakota Gaines, the Intertwine Alliance’s first-ever office assistant, is 18 years old and a recent graduate of Gresham’s Centennial High. She’s starting a nursing program at Mt. Hood Community College in the spring. You’ll find her at The Intertwine Alliance office on Tuesdays and Thursdays, skillfully multitasking all we send her way.

The

The

“There’s almost no money set aside for fixing major things, but the needs aren’t visible to the average citizen,” says Nick Hardigg, Executive Director of the nonprofit

“There’s almost no money set aside for fixing major things, but the needs aren’t visible to the average citizen,” says Nick Hardigg, Executive Director of the nonprofit

“Why bond measures and levies? The answer goes back to state law,” says Heather Nelson Kent, Grants Program Manager for Metro’s Natural Areas Program.

“Why bond measures and levies? The answer goes back to state law,” says Heather Nelson Kent, Grants Program Manager for Metro’s Natural Areas Program.

For Intertwine Executive Director Mike Wetter, the rapid growth of The Intertwine Alliance (now 125-plus public, private, and nonprofit partners and counting) is evidence that large landscape thinking – backed by sustainable funding – is more possible now than ever before.

For Intertwine Executive Director Mike Wetter, the rapid growth of The Intertwine Alliance (now 125-plus public, private, and nonprofit partners and counting) is evidence that large landscape thinking – backed by sustainable funding – is more possible now than ever before. Through storytelling outlets like

Through storytelling outlets like  With credit and a humble apology, I take the title of Norman Maclean’s book A River Runs Through It and strive to make it more personal and inclusive by replacing “It” with “Us.”

With credit and a humble apology, I take the title of Norman Maclean’s book A River Runs Through It and strive to make it more personal and inclusive by replacing “It” with “Us.” Call it the happenstance of human migration, the mistakes of our mothers and fathers, progress, or opportunity; this river, which many of us see each day, has defined where we live.

Call it the happenstance of human migration, the mistakes of our mothers and fathers, progress, or opportunity; this river, which many of us see each day, has defined where we live. As the Willamette Valley changed, so did the river. Where once grasslands, oak savannas, meanders and floodplains made for a natural balance of nature, our river has now has been “tamed” into a channel.

As the Willamette Valley changed, so did the river. Where once grasslands, oak savannas, meanders and floodplains made for a natural balance of nature, our river has now has been “tamed” into a channel. We have used the Willamette for commerce, manufacturing, ship-building, industry and recreation. Yet for centuries, this river was a major source of life giving food and materials to the Native Americans. You can see where the uses conflicted with one another.

We have used the Willamette for commerce, manufacturing, ship-building, industry and recreation. Yet for centuries, this river was a major source of life giving food and materials to the Native Americans. You can see where the uses conflicted with one another. For over 18 years, I had the honor of serving Oregon as the executive director of Governor Tom McCall’s non-profit organization, SOLVE.

For over 18 years, I had the honor of serving Oregon as the executive director of Governor Tom McCall’s non-profit organization, SOLVE.

From 1990 to 2008, Jack McGowan was Executive Director of SOLVE, a coastal beach cleanup which has now spread to over 100 foreign countries. Over the past five decades, he has worked as an on-air radio and television host, assistant to Portland Mayor J.E. Bud Clark, producer of the Mt. Hood Festival of Jazz, and Public Relations Director for the Oregon Zoo. In 2013, the Port of Portland asked Jack to create the podcast series "One River, Many Voices," which interviews over 40 representatives with a stake in the restoration of the Willamette River.

From 1990 to 2008, Jack McGowan was Executive Director of SOLVE, a coastal beach cleanup which has now spread to over 100 foreign countries. Over the past five decades, he has worked as an on-air radio and television host, assistant to Portland Mayor J.E. Bud Clark, producer of the Mt. Hood Festival of Jazz, and Public Relations Director for the Oregon Zoo. In 2013, the Port of Portland asked Jack to create the podcast series "One River, Many Voices," which interviews over 40 representatives with a stake in the restoration of the Willamette River. Dear Mr. Olmsted,

Dear Mr. Olmsted,

Downtown’s South Park blocks begin just a few blocks from the north end. Then, the Parkway connects to trails in

Downtown’s South Park blocks begin just a few blocks from the north end. Then, the Parkway connects to trails in  There will be time for general conversation plus presentations on

There will be time for general conversation plus presentations on  The

The

The United States fares quite badly in terms of reported childhood wellbeing on the

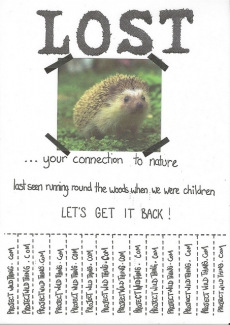

The United States fares quite badly in terms of reported childhood wellbeing on the  Project Wild Thing isn't just a film anymore. What's happened since your October 2013 release?

Project Wild Thing isn't just a film anymore. What's happened since your October 2013 release? The insight from the film is that while there's a supply of green space out there, and organizations that offer natural experiences to children and parents, in economic terms, people aren't demanding it.

The insight from the film is that while there's a supply of green space out there, and organizations that offer natural experiences to children and parents, in economic terms, people aren't demanding it.

I have to be careful how I answer so as not to be rude, but it's nonsense. If you look logically at the risk of contracting these diseases, they're vanishingly small. It's equivalent to worrying about being struck by lightning. We don't attach lightning conductors to our children's heads when we take them outside. We don't act on the risk. But for some reason in the U.K., and the U.S. I think, we act on the fear of disease or stranger danger in very illogical ways.

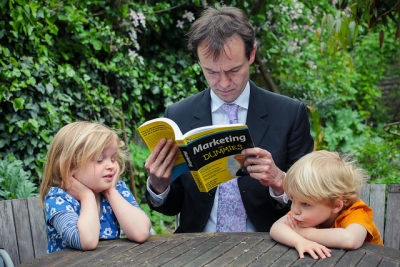

I have to be careful how I answer so as not to be rude, but it's nonsense. If you look logically at the risk of contracting these diseases, they're vanishingly small. It's equivalent to worrying about being struck by lightning. We don't attach lightning conductors to our children's heads when we take them outside. We don't act on the risk. But for some reason in the U.K., and the U.S. I think, we act on the fear of disease or stranger danger in very illogical ways. We try to be playful, to get people to see our product as fun and free.

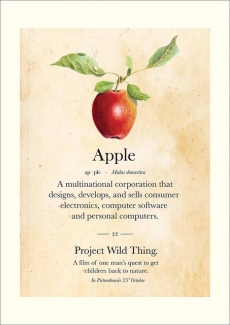

We try to be playful, to get people to see our product as fun and free. The Hunger Games is a really interesting representation of a wild life that teenagers really understand. The message is that there's something highly resilient about an outdoor person – that they're more determined, more likely to survive and be tough.

The Hunger Games is a really interesting representation of a wild life that teenagers really understand. The message is that there's something highly resilient about an outdoor person – that they're more determined, more likely to survive and be tough. Your daughter plays a big role in the film. How have your efforts to up wild time for kids worked out at home?

Your daughter plays a big role in the film. How have your efforts to up wild time for kids worked out at home? For more than 15 years,

For more than 15 years,  We also think of PYYCC as a way to bring nature to young people who may not have the means or motivation to seek it on their own, thus fostering a lifelong connection and developing our next generation of conservationists.

We also think of PYYCC as a way to bring nature to young people who may not have the means or motivation to seek it on their own, thus fostering a lifelong connection and developing our next generation of conservationists.

Michael Oliver is the program coordinator for Mount Hood Community College's

Michael Oliver is the program coordinator for Mount Hood Community College's