The U.K.’s “Marketing Director for Nature” brings his pitch to The Intertwine

Ramona DeNies, September 10 2014

David Bond wants to sell you something. He’ll say anything, really. As long as it gets you and your kids outdoors.

David Bond wants to sell you something. He’ll say anything, really. As long as it gets you and your kids outdoors.

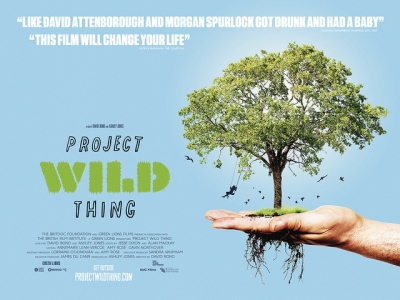

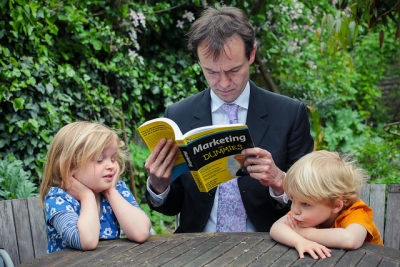

In his new documentary Project Wild Thing, the British filmmaker – alarmed that his young daughter was choosing to spend 97 percent of her waking time indoors – sets out to reverse shrinking demand for outdoor play by employing the same marketing tactics that sell Nintendos.

Now Bond is bringing his pitch to America, with a week-long set of Portland events that starts today.

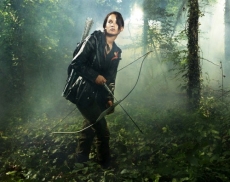

We Skyped with Bond the day before his flight, in an interview that ranged from Norwegian villages to lightning rods and Hollywood blockbuster The Hunger Games.

***

So why does the United States need Project Wild Thing?

The United States fares quite badly in terms of reported childhood wellbeing on the Unicef survey.

The United States fares quite badly in terms of reported childhood wellbeing on the Unicef survey.

Nationwide, it's a big issue for you, as it is for us in Britain, that children are less and less connected to their natural environment.

An enormous amount of the thinking that led to Project Wild Thing – from the Nature Network to Richard Louv – has come out of the States. In some ways, you're ahead of us. In other ways, you're really a catastrophic representation of what can go wrong.

What’s gone wrong?

We've identified 11 major barriers between children and the outdoors, things that are high in the U.S. and U.K.. Things like traffic and road safety, perceptions toward stranger danger (fear of strangers in the media).

A risk averse, litigious culture makes it hard for organizations to let children roam freely without panicking about the risks.

Project Wild Thing isn't just a film anymore. What's happened since your October 2013 release?

Project Wild Thing isn't just a film anymore. What's happened since your October 2013 release?

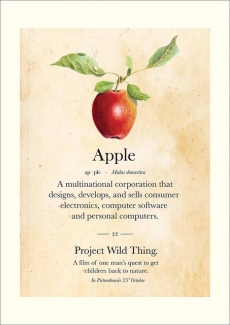

Well, in the film, as a kind of joke, I appoint myself the Marketing Director of Nature, and then we start this campaign to try to sell nature to children. In the process, we actually do a campaign – we get lots of free ad space and creatives helping us.

As a result of doing that, we got a lot of real people coming and saying “we want to join the movement.” We started signing people up, and the Wild Network was born. Now it has thousands of members, and quite a wide reach. It's been amazing to see, just in the last months since we launched.

What does the Wild Network do?

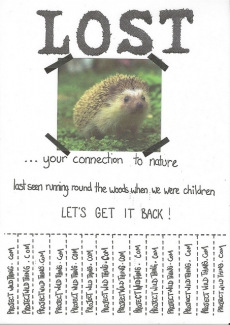

The insight from the film is that while there's a supply of green space out there, and organizations that offer natural experiences to children and parents, in economic terms, people aren't demanding it.

The insight from the film is that while there's a supply of green space out there, and organizations that offer natural experiences to children and parents, in economic terms, people aren't demanding it.

The reason for this shrinking demand is that the alternatives are demanded more voraciously: screen time, computer games, time indoors playing with toys. The Wild Network exists so that all of the organizations that want to sell outdoor play to children can use it to make a big noise about the benefits of their product.

When will you know that this big marketing noise is successful?

If you're marketing Nintendos, you know precisely how many you sold. But there's very little measurement of outdoor time for children. So it's a challenge to figure out if we're having an effect. At the moment, we're judging success by whether debate has been stimulated in the U.K.. We're looking at creating a measurement for time spent outdoors as well.

There's a gap there that we need to figure out. Do we use proxy sales, like rubber boots? Some power companies have suggested that we correlate power consumption with time spent outdoors. We also want to ask questions like what's the most outdoorsy city and the most outdoorsy day? We need answers like these to sell nature in an ongoing, cost-effective, celebratory way.

What nations, in your opinion, should we look to? Who already does what you call "Wild Time" well?

There's that great saying, if you design a town for a child and an eighty-year-old, then you end up with a really great town. Certainly in Northern Europe and Holland, they're much better at the supremacy of the child and the older person over the automobile.

There's that great saying, if you design a town for a child and an eighty-year-old, then you end up with a really great town. Certainly in Northern Europe and Holland, they're much better at the supremacy of the child and the older person over the automobile.

I've just written a blog about the Norwegian philosophy of love of the outdoors. Land is considered to be everyone's to roam on, to move freely through fields.

Scandinavians also have the belief that children need to be plugged into the natural world from a very young age. Newborns are often taken outdoors their first day. There's a different intention there. Formal education starts later, but they end up scoring well compared to nations like ours, which school our children much younger.

How do you counter the fears of risk-averse cultures like ours?

I have to be careful how I answer so as not to be rude, but it's nonsense. If you look logically at the risk of contracting these diseases, they're vanishingly small. It's equivalent to worrying about being struck by lightning. We don't attach lightning conductors to our children's heads when we take them outside. We don't act on the risk. But for some reason in the U.K., and the U.S. I think, we act on the fear of disease or stranger danger in very illogical ways.

I have to be careful how I answer so as not to be rude, but it's nonsense. If you look logically at the risk of contracting these diseases, they're vanishingly small. It's equivalent to worrying about being struck by lightning. We don't attach lightning conductors to our children's heads when we take them outside. We don't act on the risk. But for some reason in the U.K., and the U.S. I think, we act on the fear of disease or stranger danger in very illogical ways.

In the U.K., some are reacting quite strongly to the Wild Network, saying that our product is dangerous. But it's in fact really good for you, and the alternatives are dangerous. A life lived indoors, in front of the screen, is far more sinister in terms of the long-term risks of diabetes, heart disease, obesity.

But as Nature’s Marketing Director, that’s not the sales pitch you use in the film. What’s your angle?

We try to be playful, to get people to see our product as fun and free.

We try to be playful, to get people to see our product as fun and free.

A lot of charities, NGOs, organizations who have traditionally been responsible for selling the joys of an outdoor life, have often done so through quite negative messaging: get your children outside or the climate will suffer, or they won't understand polar bears. In the Wild Network, we're trying really hard to have fun, not make people feel badly.

What demographic is proving the hardest sell so far? Parents?

Actually, it's teenagers. There's scientific evidence that says if you don't get children normalized to an outdoor life by the time they're seven or eight, then it just gets increasingly hard to persuade them to enjoy it. If you're a teenager in the depths of hormonal change, deep into social media and that's the way you're expressing yourself, having someone like me come along and say “Hey, let's put on some Wellington boots,” that's not even going to begin to break through. You'll see some of those kids in the film, who are almost unreachable.

Is there any way you've found to break into this particularly tricky market?

The Hunger Games is a really interesting representation of a wild life that teenagers really understand. The message is that there's something highly resilient about an outdoor person – that they're more determined, more likely to survive and be tough.

The Hunger Games is a really interesting representation of a wild life that teenagers really understand. The message is that there's something highly resilient about an outdoor person – that they're more determined, more likely to survive and be tough.

Teens in the U.K. respond well to a statistic that 80 percent of successful entrepreneurs were tree climbers when they were kids. So if you want to be a successful entrepreneur, a good place to hone the skills of a self-starter is in the outdoors.

So the sell there isn't climate change or understanding polar bears?

Appealing to a teenager's self-interest can be highly effective. That's been a big insight for us. You and I might respond well to an ethical consideration that we want our children to be nice to each other and know the names of plants and animals, but there are waves of people who are more motivated by financial gain or status. And these are people we have to communicate with as well. Finding those pathways has been really fun.

What's the plan for your week here in The Intertwine?

I'm really excited that a Wild Network might be launched in Portland. We're gathering nature's marketing department here for a big brainstorming. This would be the first Wild Network in the States, and we hope it might be the start of more marketing of nature by groups across the U.S..

Your daughter plays a big role in the film. How have your efforts to up wild time for kids worked out at home?

Your daughter plays a big role in the film. How have your efforts to up wild time for kids worked out at home?

Well, they know they can make me really happy just by saying they want to go outdoors more. Whether they genuinely do or not, I really don't care. My daughter, who I measured at about three percent of her waking time outdoors, is now at about twelve percent. She's actively choosing to go outdoors far more than she ever did before. So that's amazing.

Through storytelling outlets like

Through storytelling outlets like

Comments

Wild Thing

Robert Bresky

Add new comment