Why does the environmental movement lack diversity?

By Mickey Fearn, July 3 2013

“Diversity does not just expand the common ground of consensus. It also increases the larger group’s ability to solve problems." -- Steve Johnson, Future Perfect

In 1970, when I started my first job out of college at the State of California Department of Parks and Recreation, I was asked to investigate why communities of color, youth and the poor weren’t engaging with the Department, and why they didn’t seem to be interested in “wild spaces.” Four decades later, little has changed -- we’re still asking the same question.

youth and the poor weren’t engaging with the Department, and why they didn’t seem to be interested in “wild spaces.” Four decades later, little has changed -- we’re still asking the same question.

Maybe it’s time to create a deeper conversation. The Civil Rights movement gained strength when it became more than a Black American movement. Perhaps the conservation movement will likewise not realize its true power and potential until it become truly inclusive. Until we learn how to reach all Americans.

Parks for all

For decades the leadership of parks, recreation and conservation organizations has asserted  that lack of money, transportation, equipment and awareness are to blame.

that lack of money, transportation, equipment and awareness are to blame.

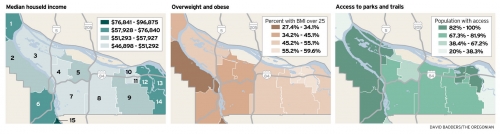

But ethnicity, culture, and socioeconomics must also be considered in getting to the complex causes of this challenge. Communities of color are often portrayed as fearful of, indifferent to or bored by nature -- I don’t care about it! I’m afraid of it! It doesn’t have meaning to me! And yet they historically outvote the general public, and even environmentalists, when it comes to conservation issues.

Beyond the Four Hit Theory

To address the lack of equity in our parks, many within the parks, recreation and conservation  profession, including myself, have tried nature programs with youth and other communities. But the assumption that creating an environmental steward is as easy as getting someone to strap a 35-pound pack on their back, hike into the wilderness, and sleep on the ground is challenged by findings from the Trust for Public Land. Echoing Covello’s Four Hit Theory, the Trust has shown that it takes a minimum of four meaningful exposures to integrate options like camping, canoeing or other wilderness activities into a person’s recreation inventory.

profession, including myself, have tried nature programs with youth and other communities. But the assumption that creating an environmental steward is as easy as getting someone to strap a 35-pound pack on their back, hike into the wilderness, and sleep on the ground is challenged by findings from the Trust for Public Land. Echoing Covello’s Four Hit Theory, the Trust has shown that it takes a minimum of four meaningful exposures to integrate options like camping, canoeing or other wilderness activities into a person’s recreation inventory.

Engaging long-disenfranchised communities in the conversation will likely take far more work  than four iterations. This is where our movement has been stuck, all these decades. To reach these underserved communities -- and get them engaged the mainstream -- we must address racial equity, socioeconomics, and environmental injustices as much as we do salmon, global warming, rainforest, old growth, forest and trails.

than four iterations. This is where our movement has been stuck, all these decades. To reach these underserved communities -- and get them engaged the mainstream -- we must address racial equity, socioeconomics, and environmental injustices as much as we do salmon, global warming, rainforest, old growth, forest and trails.

A Third Space

How do we move the conservation movement beyond addressing the symptoms (via one-off canoe trips and marketing campaigns) to the deeper reasons behind the physical disruption between nature and people of color, youth and the poor? One option: create a “Third Space” conversation.

An emerging tool based on Ray Oldenburg's eight characteristics of third places and Marshall McLuhan’s belief that solutions to complex challenges emerge in the space between the disciplines, facilitated “Third Space” conversations are designed to draw together those who may be antagonistic, indifferent, or totally unaware of each other. Engaging diverse stakeholders in emotionally challenging conversation within a neutral setting, Third Space conversations focus on what’s possible -- not what’s wrong.

An emerging tool based on Ray Oldenburg's eight characteristics of third places and Marshall McLuhan’s belief that solutions to complex challenges emerge in the space between the disciplines, facilitated “Third Space” conversations are designed to draw together those who may be antagonistic, indifferent, or totally unaware of each other. Engaging diverse stakeholders in emotionally challenging conversation within a neutral setting, Third Space conversations focus on what’s possible -- not what’s wrong.

I admit that I don’t know the answer to the question of social and racial equity in our park systems and in the conservation movement. But I do think the time is right for conversations like these -- conversations that, rather than “rescuing” urban youth and communities of color, seek to use nature to help break the restrictive cycles of racism and poverty. I also think the Pacific Northwest is the right place to start.

I welcome your thoughts on how we might begin this important work, to make sure that the next generation of environmental stewards and parks, recreation and conservation leaders reflect our true strength -- our diversity.

Mickey Fearn has been in the parks, recreation and conservation profession for over 45 years. Prior to serving as the

Mickey Fearn has been in the parks, recreation and conservation profession for over 45 years. Prior to serving as the

Add new comment