Coming together to curb controversy over city tree codes

By Brian Wegener, November 26 2014

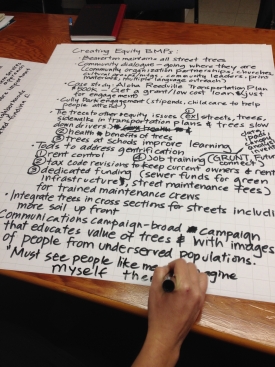

More than 80 people gathered in Tualatin last week for an extended conversation about municipal tree codes. The Nov. 18 Urban Forestry Summit, an Intertwine Alliance event led by the Oregon Department of Forestry, Tualatin Riverkeepers and arborists Teragan and Associates, allowed participants to share their challenges with local tree codes and to hear success stories from jurisdictions that have worked through these challenges.

Big takeaways: Urban tree policy works best when we know what our goals are, when we involve all stakeholders early on, and when we focus on desired outcomes rather than particular and predetermined strategies of how to achieve them.

Big takeaways: Urban tree policy works best when we know what our goals are, when we involve all stakeholders early on, and when we focus on desired outcomes rather than particular and predetermined strategies of how to achieve them.

Most of us can agree that, in the urban environment, trees provide some very significant benefits:

- Reduction of stormwater runoff, protecting urban creeks

- Shade in the summer, reducing the heat-island effect

- Capturing carbon and other air pollutants, and producing oxygen

- Beautification, habitat and increased property values

- Other less obvious but statistically documented effects ranging from calmer traffic to healthy babies

With all these benefits, you would think there would be nothing controversial about protecting our urban forests. But trees can have their down sides, too. While they benefit the entire community, the costs of protecting, maintaining and replacing trees often fall on just a few people — making efforts to regulate them contentious.

With all these benefits, you would think there would be nothing controversial about protecting our urban forests. But trees can have their down sides, too. While they benefit the entire community, the costs of protecting, maintaining and replacing trees often fall on just a few people — making efforts to regulate them contentious.

We have seen far too many cases in The Intertwine region where regulations to protect trees have had the opposite effect. Property owners have clear-cut their land before development starts in order to avoid restrictions and mitigation costs that would be incurred if trees were cut during the development process.

The opening speaker at the tree code summit, Metro Councilor and former Tigard Mayor Craig Dirksen, spoke of the vexing nature of developing a tree code. When charged with revising Tigard’s tree code, he said, city staff reacted as if they had been asked to “walk through fire every day for the next several years.” Polarized interests fell into two camps: those who wanted to punish every act of tree removal and those who wanted no restrictions at all to any action on private property.

Other conference participants described going through a several-year process of developing a tree code that satisfied one side, only to be torpedoed by the other side at the end of the process — stopping any new urban forestry policy from taking place.

Other conference participants described going through a several-year process of developing a tree code that satisfied one side, only to be torpedoed by the other side at the end of the process — stopping any new urban forestry policy from taking place.

We hold Tigard’s tree code revision process up as model because it managed to avoid this polarized approach — by involving diversified interests from the very beginning. In the end, Tigard arrived at a consensus between tree cutters and tree huggers, developers and environmentalists, for an approach that will increase tree canopy in the city from its current 25 percent to 40 percent by 2047.

One purpose of last week’s gathering was to encourage other jurisdictions to follow Tigard’s collaborative process in order to improve the effectiveness of their local urban forestry programs. Different places have different situations, and will need their own unique mix of regulation and incentives to promote healthy urban forests. But Tigard shows us that open participation of diverse interests throughout the process is the key to reaching a successful consensus.

Many important discussions were started at the summit, and many opportunities identified. My organization and other Intertwine Alliance partners are excited to move this work forward in the months and years ahead.

Brian Wegener, a Tigard resident for the past 30 years, is the Advocacy & Communications Manager for Tualatin Riverkeepers and serves on the board of Oregon Community Trees. He has worked on policy and demonstration projects promoting the use of urban forestry for stormwater management. He is also allergic to tree pollen.

Brian Wegener, a Tigard resident for the past 30 years, is the Advocacy & Communications Manager for Tualatin Riverkeepers and serves on the board of Oregon Community Trees. He has worked on policy and demonstration projects promoting the use of urban forestry for stormwater management. He is also allergic to tree pollen.

Comments

Tree ordinances

Add new comment