Turning down the heat, turning up the green

Cooling off the hottest & dirtiest places in the region

By Vivek Shandas

You’ve talked about it with your neighbors over the fence and with friends at the cookout: It’s been a pretty hot summer in the Portland area.

On some of the hottest days, I like to get in the car and drive around with Jackson Voelkel, a geospatial research analyst in my Sustaining Urban Places Research Lab at Portland State University, and Dr. David Sailor, a PSU engineering professor. It’s not just any car. It’s outfitted with sensors and temperature gauges, allowing us to locate in real time the hottest spots in Portland.

On some of the hottest days, I like to get in the car and drive around with Jackson Voelkel, a geospatial research analyst in my Sustaining Urban Places Research Lab at Portland State University, and Dr. David Sailor, a PSU engineering professor. It’s not just any car. It’s outfitted with sensors and temperature gauges, allowing us to locate in real time the hottest spots in Portland.

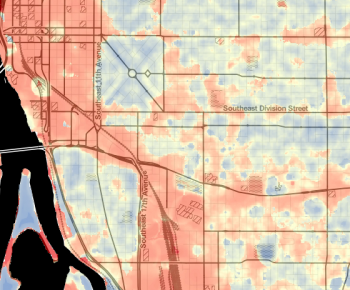

We’ve been working with a team for several years to develop heat island maps for Portland and its surrounding region. We’ve also worked with Dr. Linda George and her lab to study traffic-related air quality, and the impact of trees on that air quality. These two environmental measures help us identify the hottest and dirtiest places throughout The Intertwine, and who is particularly at risk for health problems during high-heat events.

![Resource linking the hottest and most [air] polluted places with vulnerable populations. Created by PSU's Sustaining Urban Places Research Lab. Available online to the public soon.](/sites/theintertwine.org/files/resize/pdx-resiliency-map-375x242.png) Last year, we were approached by the PSU Institute for Sustainable Solutions about working with the Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability as part of the Portland Climate Action Collaborative. The idea was to take some of our research on heat island and air quality mapping and make it applicable for city officials and public health managers looking for ways to reduce respiratory illness and other negative—potentially fatal—impacts during Portland’s heat waves. We were especially interested in reducing harm to the most vulnerable populations: the elderly, people with asthma, and children and babies.

Last year, we were approached by the PSU Institute for Sustainable Solutions about working with the Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability as part of the Portland Climate Action Collaborative. The idea was to take some of our research on heat island and air quality mapping and make it applicable for city officials and public health managers looking for ways to reduce respiratory illness and other negative—potentially fatal—impacts during Portland’s heat waves. We were especially interested in reducing harm to the most vulnerable populations: the elderly, people with asthma, and children and babies.

What many people don’t realize is that there are more deaths attributed to urban heat in the United States than all other natural disasters combined. Evidence from places where hundreds of people have died, including Chicago, St. Louis, and throughout Europe, suggests that many of those deaths occur in populations with preexisting health conditions, but also impact those with fewer financial resources to take measures like installing air conditioning. Combine a hot day with dirty air, and we have a lethal recipe for any urban community, including the Portland region.

Yet the challenge for public health workers, we learned, is to find the places where heat islands, degraded air quality, and vulnerable populations exist in the same place. At the same time, the challenge for planners is to consider the policy and design options that can cool and clean city neighborhoods.

Yet the challenge for public health workers, we learned, is to find the places where heat islands, degraded air quality, and vulnerable populations exist in the same place. At the same time, the challenge for planners is to consider the policy and design options that can cool and clean city neighborhoods.

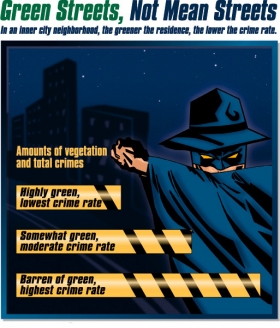

By layering demographic data on top of our heat island and air quality maps, we’ve been able to uncover the factors that contribute to human vulnerability. It’s no surprise that wealthy neighborhoods with mature trees, such as Irvington in Northeast Portland, Ladd's Adddition in Southeast Portland, and Portland Heights in Southwest Portland, are much better off than lower-income neighborhoods with less greenery, such as Cully in Northeast Portland, Foster-Powell in Southeast Portland, and St. Johns in North Portland. Perhaps surprising is that the same system of inclusion and exclusion of tree-filled neighborhoods has the same results in the 12 other U.S. cities we’ve studied. In other words, the current climate adaptation picture isn’t very equitable.

Approved earlier this summer by Portland City Council and Multnomah County, the 2015 Portland Climate Action Plan includes our layered maps (on page 112). We believe that sharing our timely research with the city and county was a first step in helping us to understand what strategies, programs, infrastructure, and policies need to be put in place to ensure a more equitable approach to climate mitigation in the region.

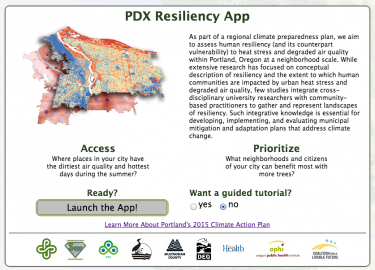

Right now we’re working on an interactive version of the map that will help policy makers and citizen groups drill down on specific Portland streets and neighborhoods to find trouble spots. Notable in our analysis is that trails and greenways factor prominently in reducing air pollution and mitigating urban heat. The more extensive tracts of greenery present in specific areas, the greater cleaning and cooling of the air. Our wish is that such interactive maps will help generate a conversation about areas of the city that need attention, to work with local organizations to bring awareness about environmental conditions, and ultimately to take action to cool and clean the city, one neighborhood at a time.

Right now we’re working on an interactive version of the map that will help policy makers and citizen groups drill down on specific Portland streets and neighborhoods to find trouble spots. Notable in our analysis is that trails and greenways factor prominently in reducing air pollution and mitigating urban heat. The more extensive tracts of greenery present in specific areas, the greater cleaning and cooling of the air. Our wish is that such interactive maps will help generate a conversation about areas of the city that need attention, to work with local organizations to bring awareness about environmental conditions, and ultimately to take action to cool and clean the city, one neighborhood at a time.

There are several ways to cut down on heat island effects in urban areas. You can reduce the reflectivity of surfaces, such as changing a black parking lot or rooftop to a lighter color; reduce the amount of connected concrete in a neighborhood; and, of course, plant more and greater continuity of trees. We are in the process of developing an approach that brings together existing information about effective strategies as part of a tailored online mapping tool. We expect to release the tool this winter 2016.

We also want to know where urban tree planting can have the most positive impact. Recently the SUPR Lab released the Trees and Health APP, an online tool that allows anyone to scan city neighborhoods and find the ones most in need of trees. The APP, which stands for Assess, Prioritize and Plan, is part of a U.S. Forest Service-sponsored project named Healthy Trees, Healthy People. So far, the tool is available in 13 cities, including Portland, and we would like to expand it to more. We would welcome members of the Intertwine Alliance to use and evaluate the tool by assessing the extent to which your specific goals align with the current challenges facing the region.

We also want to know where urban tree planting can have the most positive impact. Recently the SUPR Lab released the Trees and Health APP, an online tool that allows anyone to scan city neighborhoods and find the ones most in need of trees. The APP, which stands for Assess, Prioritize and Plan, is part of a U.S. Forest Service-sponsored project named Healthy Trees, Healthy People. So far, the tool is available in 13 cities, including Portland, and we would like to expand it to more. We would welcome members of the Intertwine Alliance to use and evaluate the tool by assessing the extent to which your specific goals align with the current challenges facing the region.

I’m thrilled to see attention being given to the relationship between nature and health, especially the role of trees as part of our healthcare plan. I’m noticing that the health and well-being benefits of urban trees are getting into the mainstream media, and that policy makers and citizen groups are paying attention.

So as you talk to your neighbors and friends about the hot summer, you might also consider asking them about how your neighborhood can accommodate more trees. You might be surprised by their responses!

Vivek Shandas is an Associate Professor in the Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning at Portland State University. He's also founder of the

Vivek Shandas is an Associate Professor in the Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning at Portland State University. He's also founder of the  Resting on our laurels? Perhaps. But on the coolest day in August,

Resting on our laurels? Perhaps. But on the coolest day in August,  From the beginning, the ride has been designed to connect the dots between what's on the ground, what's in the works, and what's on the visionary drawing board for cycling and alternative transportation.

From the beginning, the ride has been designed to connect the dots between what's on the ground, what's in the works, and what's on the visionary drawing board for cycling and alternative transportation. The ride illuminated the work that remains to be done on the Willamette's west bank. North Williams is one of the city's busiest commuting corridors, and 40 percent of the traffic during rush hour now pedals in the

The ride illuminated the work that remains to be done on the Willamette's west bank. North Williams is one of the city's busiest commuting corridors, and 40 percent of the traffic during rush hour now pedals in the  "It's not convenient. It's not intuitive. And it's not safe," Stude says. "The solution is far more about commitment and politics than engineering. When we look at this public space, what do we choose to prioritize? We've prioritized movement over safety."

"It's not convenient. It's not intuitive. And it's not safe," Stude says. "The solution is far more about commitment and politics than engineering. When we look at this public space, what do we choose to prioritize? We've prioritized movement over safety." Steve Duin is The Oregonian's Metro columnist. He is the author/co-author of six books, including "Comics: Between the Panels," a history of comics; "Father Time," a collection of his columns on family and fatherhood; and a graphic novel, "Oil and Water." His last name, for inexplicable reasons, is pronounced "Dean." Blog:

Steve Duin is The Oregonian's Metro columnist. He is the author/co-author of six books, including "Comics: Between the Panels," a history of comics; "Father Time," a collection of his columns on family and fatherhood; and a graphic novel, "Oil and Water." His last name, for inexplicable reasons, is pronounced "Dean." Blog:  Many are familiar with the

Many are familiar with the  The free-flowing East Fork of the Lewis River is home to native runs of Chinook, Coho and Chum salmon, and winter and summer steelhead. The lower floodplain offers hundreds of acres of bottomland habitat for waterfowl and other species. Clark County and its partners have assembled more than 2,000 acres of land from the confluence of the East Fork and North Fork Lewis Rivers to Lewisville Park near Battle Ground. While much of this land is protected for its habitat value and has limited public access,

The free-flowing East Fork of the Lewis River is home to native runs of Chinook, Coho and Chum salmon, and winter and summer steelhead. The lower floodplain offers hundreds of acres of bottomland habitat for waterfowl and other species. Clark County and its partners have assembled more than 2,000 acres of land from the confluence of the East Fork and North Fork Lewis Rivers to Lewisville Park near Battle Ground. While much of this land is protected for its habitat value and has limited public access,  you will arrive at a waterfowl viewing blind where you may see migrating tundra swans feeding on camas bulbs in the wetland ponds. Migrating salmon smolts also use the ponds for refuge and forage. From the large bridge across Brezee Creek, there is an expansive view of the bottomland landscape. As you look upstream, know that most of the bottomlands on the south side of the river are protected. Continuing over the bridge, the trail narrows and follows the levee, providing more intimate views of the river.

you will arrive at a waterfowl viewing blind where you may see migrating tundra swans feeding on camas bulbs in the wetland ponds. Migrating salmon smolts also use the ponds for refuge and forage. From the large bridge across Brezee Creek, there is an expansive view of the bottomland landscape. As you look upstream, know that most of the bottomlands on the south side of the river are protected. Continuing over the bridge, the trail narrows and follows the levee, providing more intimate views of the river.  The Lewis and Washougal River systems are the two primary systems we expect to contribute to the recovery of salmon and steelhead populations in Clark County. The City of Camas, Clark County and other partners have managed to assemble an 100-acre greenway along the Lower Washougal River. The City recently completed a 1.5 mile-long handicap-accessible

The Lewis and Washougal River systems are the two primary systems we expect to contribute to the recovery of salmon and steelhead populations in Clark County. The City of Camas, Clark County and other partners have managed to assemble an 100-acre greenway along the Lower Washougal River. The City recently completed a 1.5 mile-long handicap-accessible  Patrick Lee is a greenspaces geezer, proud of his accomplishments to date and excited about the work to come. He coordinates Clark County’s Legacy Lands Program.

Patrick Lee is a greenspaces geezer, proud of his accomplishments to date and excited about the work to come. He coordinates Clark County’s Legacy Lands Program.

Intertwine Alliance Executive Director Mike Wetter has directed the coalition since its early days as a Metro initiative, before it became a formal nonprofit in 2011. Mike was chief of staff to former Metro Council President David Bragdon, and a business consultant for 13 years serving public, private and nonprofit clients. A visionary leader full of creative ideas, he's an avid whitewater rafter, kayaker, cyclist and hiker.

Intertwine Alliance Executive Director Mike Wetter has directed the coalition since its early days as a Metro initiative, before it became a formal nonprofit in 2011. Mike was chief of staff to former Metro Council President David Bragdon, and a business consultant for 13 years serving public, private and nonprofit clients. A visionary leader full of creative ideas, he's an avid whitewater rafter, kayaker, cyclist and hiker. Many of us remember walking or bicycling to and from school as children. In fact, a generation ago, in 1969, nearly 50 percent of the U.S. population did so. Today that figure stands at 13 percent.

Many of us remember walking or bicycling to and from school as children. In fact, a generation ago, in 1969, nearly 50 percent of the U.S. population did so. Today that figure stands at 13 percent. The reality is that too often transit-access projects, projects that improve safe routes around schools and neighborhood centers, and projects that provide healthy options for traveling distances shorter than 3 miles (which account for 44 percent of all trips, and could easily be replaced by walking or bicycling) have not traditionally been successful in a constrained funding environment. The reality is that most people do not recognize or understand the benefit of solidly investing in active transportation projects, or of the benefit they bring to the transportation system we all rely upon.

The reality is that too often transit-access projects, projects that improve safe routes around schools and neighborhood centers, and projects that provide healthy options for traveling distances shorter than 3 miles (which account for 44 percent of all trips, and could easily be replaced by walking or bicycling) have not traditionally been successful in a constrained funding environment. The reality is that most people do not recognize or understand the benefit of solidly investing in active transportation projects, or of the benefit they bring to the transportation system we all rely upon.

We know there is a great need to continue these conversations, and to add to them, which was confirmed by the energy in the room and the difficulty keeping the conversation to one topic at a time. We are already at work planning the next forum, and welcome your input.

We know there is a great need to continue these conversations, and to add to them, which was confirmed by the energy in the room and the difficulty keeping the conversation to one topic at a time. We are already at work planning the next forum, and welcome your input.  With a background in cultural anthropology, an interest in the effects of transportation choices on our health and the environment, and two boys under the age of 6, Kari Schlosshauer has brought a diversity of experience working around the globe to her role as the Pacific Northwest Regional Policy Manager for the Safe Routes to School National Partnership. She works in the Portland and Salem metropolitan regions and Southwest Washington to increase funding opportunities and improve transportation policies that support safe, healthy walking and bicycling opportunities for children and families.

With a background in cultural anthropology, an interest in the effects of transportation choices on our health and the environment, and two boys under the age of 6, Kari Schlosshauer has brought a diversity of experience working around the globe to her role as the Pacific Northwest Regional Policy Manager for the Safe Routes to School National Partnership. She works in the Portland and Salem metropolitan regions and Southwest Washington to increase funding opportunities and improve transportation policies that support safe, healthy walking and bicycling opportunities for children and families.

Juan Carlos Ocaña-Chíu is the Equity Program Analyst at Metro, where he works closely with community-based organizations to find creative ways to measure equity throughout the region. He lives in Portland's Lents neighborhood.

Juan Carlos Ocaña-Chíu is the Equity Program Analyst at Metro, where he works closely with community-based organizations to find creative ways to measure equity throughout the region. He lives in Portland's Lents neighborhood.

This fall, why not nurture your inner child on the

This fall, why not nurture your inner child on the

In addition, this bicycle-related travel spending directly supported about 4,600 jobs, resulting in $102 million in earnings. The spending also generated local and state tax receipts of nearly $18 million in 2012. This includes lodging taxes, motor fuel and travel-generated state income tax.

In addition, this bicycle-related travel spending directly supported about 4,600 jobs, resulting in $102 million in earnings. The spending also generated local and state tax receipts of nearly $18 million in 2012. This includes lodging taxes, motor fuel and travel-generated state income tax.

Nastassja Pace is

Nastassja Pace is

Kurt Beil, ND, LAc, MPH is a holistic physician and researcher at the

Kurt Beil, ND, LAc, MPH is a holistic physician and researcher at the  I stopped riding my bike about 15 years ago, due to a busy career and parenthood in San Francisco coupled with a strong disinterest in riding up hills. When I moved to Portland three years ago, I told friends who pestered me to ride that I wasn’t comfortable biking in traffic. Frankly, I could think of many other ways to exercise, socialize, and get outside. Biking just seemed like too much discomfort to deal with. But July of this year, I finally acquiesced, riding the

I stopped riding my bike about 15 years ago, due to a busy career and parenthood in San Francisco coupled with a strong disinterest in riding up hills. When I moved to Portland three years ago, I told friends who pestered me to ride that I wasn’t comfortable biking in traffic. Frankly, I could think of many other ways to exercise, socialize, and get outside. Biking just seemed like too much discomfort to deal with. But July of this year, I finally acquiesced, riding the  Getting me back on my bike wasn’t simply the result of peer pressure. As CEO of the

Getting me back on my bike wasn’t simply the result of peer pressure. As CEO of the

Since my ride on the Springwater Corridor, I’m happy to report that my bike hasn’t returned to hibernation – not after the accomplishment I felt pedaling 25 miles of the

Since my ride on the Springwater Corridor, I’m happy to report that my bike hasn’t returned to hibernation – not after the accomplishment I felt pedaling 25 miles of the  These first-hand experiences have shown me the enormous potential we have here in East Multnomah County to connect the routes we have, such as linking the Springwater Trail to Troutdale, and the Gresham-Fairview Trail to Marine Drive. But they’ve also given me a personal reason to see our Initiative succeed. Now that I’ve rediscovered the afterglow of biking with friends and colleagues – celebrating our efforts afterward over excellent bites, drinks, and service – I’m looking forward to inviting friends to join me on some of the new itineraries that come out of the

These first-hand experiences have shown me the enormous potential we have here in East Multnomah County to connect the routes we have, such as linking the Springwater Trail to Troutdale, and the Gresham-Fairview Trail to Marine Drive. But they’ve also given me a personal reason to see our Initiative succeed. Now that I’ve rediscovered the afterglow of biking with friends and colleagues – celebrating our efforts afterward over excellent bites, drinks, and service – I’m looking forward to inviting friends to join me on some of the new itineraries that come out of the

Alison Hart,

Alison Hart,

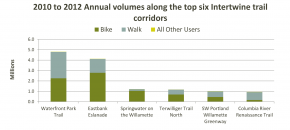

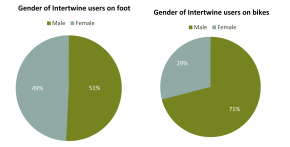

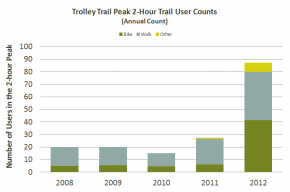

But who’s actually using our trails? How many of us? And why? For one week each September, Metro mobilizes a small army of dedicated volunteers for

But who’s actually using our trails? How many of us? And why? For one week each September, Metro mobilizes a small army of dedicated volunteers for

Nick Falbo is a planner at

Nick Falbo is a planner at