In the pre-Intertwine days, Metro’s Blue Ribbon Committee for Trails thoughtfully strategized about how to fund the region’s vision for an interconnected network of trails. Supported by a team led by Metro and including staff from the City of Portland, Oregon State Parks, the City of Forest Grove, and Alta Planning and Design, the Committee published a report in 2008 that recommended an integrated strategy to address congestion, climate change, fuel costs and the lack of funding for traditional transportation projects. One of the strategies discussed was private funding through foundations, corporations and developers.

Following that, the Executive Council for Active Transportation, chaired by Moda Vice President and current Intertwine Alliance Board President Jonathan Nicholas, convened in March 2009 to provide leadership and support for the completion of the regional network of on- and off-street bikeways and walkways, and guided Metro to apply for a $98 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation through its highly competitive Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) program.

Ambitious in scope, the grant would have funded close to 100 miles of bikeways in North/Northeast Portland, Hillsboro, Milwaukie, Clackamas County, Boring and unincorporated Clackamas County, as well as outreach and encouragement programs.

Metro was not awarded the grant. What can we learn from this? Let’s look at two trails that did get funded: the 8-mile-long, $63-million Indianapolis Cultural Trail and the 36-mile, $30- million Razorback Regional Greenway in Northwest Arkansas.

Metro was not awarded the grant. What can we learn from this? Let’s look at two trails that did get funded: the 8-mile-long, $63-million Indianapolis Cultural Trail and the 36-mile, $30- million Razorback Regional Greenway in Northwest Arkansas.

What is of note is the extent to which these two projects leveraged private donations. The Glick Family in Indianapolis, for example, committed $15 million as a lead gift, which, along with an additional $12.5 million in private funds, was used as match for the $20.5 million TIGER grant and $15 million in additional federal funding. The Cultural Trail’s history is deeply intertwined with Indianapolis’ efforts to become more bike friendly, as explained to many of us by Mayor Greg Ballard on the 2014 Cycle Oregon Policymakers ride.

Seeing the Indianapolis trail up close is a revelation. It’s simply gorgeous. The two-way cycle track forms a loop along one-way streets. Its surface is brick-like smooth pavers, graced by wand-like pedestrian-scale lights, interesting artwork, and interpretative signage, including a “Peace Walk” gallery celebrating some of history’s great legends. Every intersection and driveway is well-marked, signed and functional. An unexpected gem is a formerly grimy alley turned trail segment, with added art and the scent of roses pumped through a steam grate. A round of applause to Kevin Osborne at Rundell Ernstberger Associates, LLC, the lead trail design firm.

The Cultural Trail connects every single arts venue in downtown, and is a huge asset for tourists, local visitors and thousands of downtown workers. It was a catalyst for the Indianapolis Pacer-sponsored bike share system, and has spurred an estimated $864.5 million of economic impact.

Now let’s turn to the Northwest Arkansas Razorback Regional Greenway, which Alta led from concept to design, through construction and ribbon-cutting on May 2 of this year. The greenway links the six major municipalities of Northwest Arkansas, the University of Arkansas, hospitals, commercial centers, 36 local schools, and the headquarters of three fortune 500 companies. The new greenway will increase connectivity, drive economic development, improve residents’ health, and help make Northwest Arkansas a more attractive place to live, work and play.

Now let’s turn to the Northwest Arkansas Razorback Regional Greenway, which Alta led from concept to design, through construction and ribbon-cutting on May 2 of this year. The greenway links the six major municipalities of Northwest Arkansas, the University of Arkansas, hospitals, commercial centers, 36 local schools, and the headquarters of three fortune 500 companies. The new greenway will increase connectivity, drive economic development, improve residents’ health, and help make Northwest Arkansas a more attractive place to live, work and play.

Again, private vision –— and monies — drove the project forward at a swift pace, going from concept to ribbon-cutting in just five years. The story goes something like this: Some of the local jurisdictions and developers had started building trails. Rob Brothers from the Walton Family Foundation got concerned about design quality and lack of overall vision. He called Alta Principal Jeff Olson, and within short order, a meeting in Arkansas had been arranged.

Along with Greenways, Inc.’s *Chuck Flink and greenway specialist Bob Searns, the concept of connecting the pieces via a cohesive greenway was sparked over large maps and later deepened in a multi-day charrette, which engaged community leaders and stakeholders up and down the corridor to build support and collectively create a vision and conceptual alignment. With private funding provided by the Walton Family Foundation, the project developed a detailed alignment plan, filed a Categorical Exclusion application, and conducted cost-benefit analysis to estimate the positive economic impact health and air-quality improvements for the TIGER grant application.

As with the Cultural Trail, private money leveraged other funding. The $15 million TIGER grant was matched by more than $15 million of Walton Family Foundation funds. Other funds raised in support of the project came from the Home Depot Foundation, National Urban Forestry Grant, EPA 319 Water Quality Grant, USDOT TCSP Grant, USDOT TAP Grant, the Endeavor Foundation, the City of Fayetteville, the City of Springdale, the City of Rogers, and Mercy Hospital. All totaled, more than $35 million in funding has gone toward construction of the Razorback Regional Greenway.

As with the Cultural Trail, private money leveraged other funding. The $15 million TIGER grant was matched by more than $15 million of Walton Family Foundation funds. Other funds raised in support of the project came from the Home Depot Foundation, National Urban Forestry Grant, EPA 319 Water Quality Grant, USDOT TCSP Grant, USDOT TAP Grant, the Endeavor Foundation, the City of Fayetteville, the City of Springdale, the City of Rogers, and Mercy Hospital. All totaled, more than $35 million in funding has gone toward construction of the Razorback Regional Greenway.

Also well worth mentioning are the unsung heroes of the project: the 129 property owners who granted us no-cost easements.

Why was the TIGER application successful? “There is no doubt in my mind that the application was successful because of three things,” explains Sandy Nickerson of the Walton Foundation Family. “One, regional unity. We had 40 letters of support from all the mayors, senators and representatives, the secretary of state, the State Highway Commission, even the governor. Two, the Walton Foundation Family match, and three, the quality of the application.”

Intrigued by the Razorback Greenway, the Hyde Family Foundation and the Wolf River Conservancy recently brought in Alta to plan, design and oversee construction for 18 miles of the Wolf River Greenway in Memphis, Tennessee. Built in phases, the Wolf River Greenway will eventually extend a total of 36 miles to connect neighborhoods from the Mississippi River, north of downtown Memphis, through the cities of Germantown and Collierville, Tennessee.

Whereas Portland’s signature trails, such as the Eastbank Esplanade, Springwater Corridor, Trolley Trail and Tonquin Trail, were publicly funded, the out-of-state projects described above share the common thread of private investment by foundations dreaming of a healthier lifestyle and wishing to invest in their communities. From what we’ve observed, the private funding not only leverages public funding, it speeds up the process, gains public trust and leads to big results.

Why hasn’t this happened yet in Portland, where we have trail plans and experience and dreams just as bold as Indianapolis, Northwest Arkansas, and Memphis? Could it?

Something to think about: Because we have been successful building trails using public funds, perhaps we haven’t considered private funding as an option, need, or even desire. Major donors have favored such causes as arts venues and medical research, not trails. This could change.

Another observation: In our region, it is hard to achieve unity around a single signature corridor project like those described above. There are so many competing priorities! And we are process-oriented to the extreme, well beyond what we see in most other communities. But if a group of local governments and local foundations or corporations could, indeed, unify around a single corridor, just think of what we could achieve.

A third is identity. The razorback (hog) is the University of Arkansas mascot. The Indianapolis Cultural Trail and the Wolf River Greenway speak volumes about what those areas wanted to create. Branding can make a difference.

There is no doubt in our minds that the Intertwine partners are heading in the right direction through our collective impact approach. Private investment could be the key to our ultimate success.

*Alta and Greenways, Inc. merged in 2010.

Living in Portland, I feel fortunate to be surrounded by natural beauty and to have great hiking and outdoor resources all around me. But as a wheelchair user, I also feel frustration. Where’s the information I need to access these hiking opportunities?

Living in Portland, I feel fortunate to be surrounded by natural beauty and to have great hiking and outdoor resources all around me. But as a wheelchair user, I also feel frustration. Where’s the information I need to access these hiking opportunities?  With the right information (a simple and empowering concept) people could make their own determinations – and avoid the frustration of visiting an outdoor site only to discover that it is unusable, perhaps for the most inconsequential reason.

With the right information (a simple and empowering concept) people could make their own determinations – and avoid the frustration of visiting an outdoor site only to discover that it is unusable, perhaps for the most inconsequential reason. Starting in 2009, the new committee drew from our collective experience to develop AR’s Guidelines for Providing Trail Information to People with Disabilities.

Starting in 2009, the new committee drew from our collective experience to develop AR’s Guidelines for Providing Trail Information to People with Disabilities.  Now, AR is working to apply the Guidelines’ principles to create a Regional Online Trail Map. This map will place photos, videos and descriptions of significant features along trails that are mapped using simple smart-phone technology.

Now, AR is working to apply the Guidelines’ principles to create a Regional Online Trail Map. This map will place photos, videos and descriptions of significant features along trails that are mapped using simple smart-phone technology. The Trail Map is being supported by a generous Nature in Neighborhoods grant from Metro, and initially will cover only the Metro region. Map data will become available to the public incrementally, as 24 or more selected trails are mapped over the next two years. Half of these trails will feature videos as well as photos.

The Trail Map is being supported by a generous Nature in Neighborhoods grant from Metro, and initially will cover only the Metro region. Map data will become available to the public incrementally, as 24 or more selected trails are mapped over the next two years. Half of these trails will feature videos as well as photos.

Georgena Moran is the Founder and Project Coordinator of

Georgena Moran is the Founder and Project Coordinator of  Metro was not awarded the grant. What can we learn from this? Let’s look at two trails that did get funded: the 8-mile-long, $63-million

Metro was not awarded the grant. What can we learn from this? Let’s look at two trails that did get funded: the 8-mile-long, $63-million  Now let’s turn to the Northwest Arkansas

Now let’s turn to the Northwest Arkansas  As with the Cultural Trail, private money leveraged other funding. The $15 million TIGER grant was matched by more than $15 million of Walton Family Foundation funds. Other funds raised in support of the project came from the Home Depot Foundation, National Urban Forestry Grant, EPA 319 Water Quality Grant, USDOT TCSP Grant, USDOT TAP Grant, the Endeavor Foundation, the City of Fayetteville, the City of Springdale, the City of Rogers, and Mercy Hospital. All totaled, more than $35 million in funding has gone toward construction of the Razorback Regional Greenway.

As with the Cultural Trail, private money leveraged other funding. The $15 million TIGER grant was matched by more than $15 million of Walton Family Foundation funds. Other funds raised in support of the project came from the Home Depot Foundation, National Urban Forestry Grant, EPA 319 Water Quality Grant, USDOT TCSP Grant, USDOT TAP Grant, the Endeavor Foundation, the City of Fayetteville, the City of Springdale, the City of Rogers, and Mercy Hospital. All totaled, more than $35 million in funding has gone toward construction of the Razorback Regional Greenway.  Katie Mangle leads a group of 17 planners, designers and engineers in Alta Planning + Design’s Portland office. She is a former senior planning official of both the cities of Milwaukie and Wilsonville.

Katie Mangle leads a group of 17 planners, designers and engineers in Alta Planning + Design’s Portland office. She is a former senior planning official of both the cities of Milwaukie and Wilsonville. Mia Birk is Alta’s CEO, a pioneer in active transportation, and author of Joyride: Pedaling Toward a Healthier Planet, which tells the story of how a group of determined visionaries transformed Portland into a cycling mecca and inspired the nation.

Mia Birk is Alta’s CEO, a pioneer in active transportation, and author of Joyride: Pedaling Toward a Healthier Planet, which tells the story of how a group of determined visionaries transformed Portland into a cycling mecca and inspired the nation. Many are familiar with the

Many are familiar with the  The free-flowing East Fork of the Lewis River is home to native runs of Chinook, Coho and Chum salmon, and winter and summer steelhead. The lower floodplain offers hundreds of acres of bottomland habitat for waterfowl and other species. Clark County and its partners have assembled more than 2,000 acres of land from the confluence of the East Fork and North Fork Lewis Rivers to Lewisville Park near Battle Ground. While much of this land is protected for its habitat value and has limited public access,

The free-flowing East Fork of the Lewis River is home to native runs of Chinook, Coho and Chum salmon, and winter and summer steelhead. The lower floodplain offers hundreds of acres of bottomland habitat for waterfowl and other species. Clark County and its partners have assembled more than 2,000 acres of land from the confluence of the East Fork and North Fork Lewis Rivers to Lewisville Park near Battle Ground. While much of this land is protected for its habitat value and has limited public access,  you will arrive at a waterfowl viewing blind where you may see migrating tundra swans feeding on camas bulbs in the wetland ponds. Migrating salmon smolts also use the ponds for refuge and forage. From the large bridge across Brezee Creek, there is an expansive view of the bottomland landscape. As you look upstream, know that most of the bottomlands on the south side of the river are protected. Continuing over the bridge, the trail narrows and follows the levee, providing more intimate views of the river.

you will arrive at a waterfowl viewing blind where you may see migrating tundra swans feeding on camas bulbs in the wetland ponds. Migrating salmon smolts also use the ponds for refuge and forage. From the large bridge across Brezee Creek, there is an expansive view of the bottomland landscape. As you look upstream, know that most of the bottomlands on the south side of the river are protected. Continuing over the bridge, the trail narrows and follows the levee, providing more intimate views of the river.  The Lewis and Washougal River systems are the two primary systems we expect to contribute to the recovery of salmon and steelhead populations in Clark County. The City of Camas, Clark County and other partners have managed to assemble an 100-acre greenway along the Lower Washougal River. The City recently completed a 1.5 mile-long handicap-accessible

The Lewis and Washougal River systems are the two primary systems we expect to contribute to the recovery of salmon and steelhead populations in Clark County. The City of Camas, Clark County and other partners have managed to assemble an 100-acre greenway along the Lower Washougal River. The City recently completed a 1.5 mile-long handicap-accessible  Patrick Lee is a greenspaces geezer, proud of his accomplishments to date and excited about the work to come. He coordinates Clark County’s Legacy Lands Program.

Patrick Lee is a greenspaces geezer, proud of his accomplishments to date and excited about the work to come. He coordinates Clark County’s Legacy Lands Program.

This fall, why not nurture your inner child on the

This fall, why not nurture your inner child on the

In addition, this bicycle-related travel spending directly supported about 4,600 jobs, resulting in $102 million in earnings. The spending also generated local and state tax receipts of nearly $18 million in 2012. This includes lodging taxes, motor fuel and travel-generated state income tax.

In addition, this bicycle-related travel spending directly supported about 4,600 jobs, resulting in $102 million in earnings. The spending also generated local and state tax receipts of nearly $18 million in 2012. This includes lodging taxes, motor fuel and travel-generated state income tax.

Nastassja Pace is

Nastassja Pace is  Imagine this: from downtown Portland, you head west by foot or bike along the Columbia River all the way to coastal Tillamook, then return to the city by following the wild Salmonberry River. And that’s just your halfway mark! Next, you head east through the Columbia Gorge, turning right at Hood River, up to Mount Hood and through Estacada -- still by trail -- all the way back to Portland.

Imagine this: from downtown Portland, you head west by foot or bike along the Columbia River all the way to coastal Tillamook, then return to the city by following the wild Salmonberry River. And that’s just your halfway mark! Next, you head east through the Columbia Gorge, turning right at Hood River, up to Mount Hood and through Estacada -- still by trail -- all the way back to Portland. The Infinity Loop isn’t new, when broken down into its trail components. Many people have invested much time developing the

The Infinity Loop isn’t new, when broken down into its trail components. Many people have invested much time developing the  At a meeting a few years ago, Portland State University’s

At a meeting a few years ago, Portland State University’s  Sound farfetched? Not to Metro, which is set to

Sound farfetched? Not to Metro, which is set to  Once complete, however, few of the world’s great trails will be able to compete with the Infinity Loop’s range of iconic elements. And beyond our natural wonders, Northwest Oregon is also one of the few rare places that has the advocates and enthusiasm to pull off a project of this scope.

Once complete, however, few of the world’s great trails will be able to compete with the Infinity Loop’s range of iconic elements. And beyond our natural wonders, Northwest Oregon is also one of the few rare places that has the advocates and enthusiasm to pull off a project of this scope. Mark Davison is a

Mark Davison is a

We believe the project site, the 22-acre former Blue Heron paper mill in Oregon City, could someday serve as an economic engine, a waterfront destination, a unique habitat, a window into Oregon’s past – and a bold step into our future.

We believe the project site, the 22-acre former Blue Heron paper mill in Oregon City, could someday serve as an economic engine, a waterfront destination, a unique habitat, a window into Oregon’s past – and a bold step into our future. The former mill is for sale, but the site’s complexity and risks have required a careful and methodical transition to new uses. With the help of our consulting team, Oregon City, Clackamas County, Metro, the State of Oregon, and the property’s bankruptcy trustee, we have been working closely over the past year to develop a

The former mill is for sale, but the site’s complexity and risks have required a careful and methodical transition to new uses. With the help of our consulting team, Oregon City, Clackamas County, Metro, the State of Oregon, and the property’s bankruptcy trustee, we have been working closely over the past year to develop a  The Riverwalk we've proposed in the master plan would be a catalyst for economic development in Oregon City, and also enhance the site's development value by demonstrating the public’s commitment to improvements. It would attract visitors and generate momentum for continued implementation of the master plan.

The Riverwalk we've proposed in the master plan would be a catalyst for economic development in Oregon City, and also enhance the site's development value by demonstrating the public’s commitment to improvements. It would attract visitors and generate momentum for continued implementation of the master plan. You can help shape that change, by joining our

You can help shape that change, by joining our  Ken Pirie is a senior associate with

Ken Pirie is a senior associate with

Another exciting development this year is our partnership with

Another exciting development this year is our partnership with  Renee returned to

Renee returned to

From the depot, cyclists will also have access to other outdoor activities such as kayaking and jet boating to the base of Willamette Falls, whitewater rafting down the lower Clackamas, and paddling on stand-up boards in the

From the depot, cyclists will also have access to other outdoor activities such as kayaking and jet boating to the base of Willamette Falls, whitewater rafting down the lower Clackamas, and paddling on stand-up boards in the  Blane Meier is the owner of

Blane Meier is the owner of

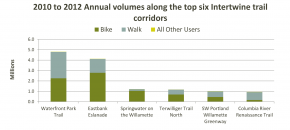

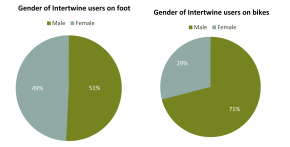

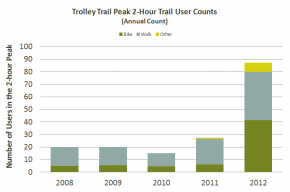

But who’s actually using our trails? How many of us? And why? For one week each September, Metro mobilizes a small army of dedicated volunteers for

But who’s actually using our trails? How many of us? And why? For one week each September, Metro mobilizes a small army of dedicated volunteers for

Nick Falbo is a planner at

Nick Falbo is a planner at

Had things gone differently, Thurman Street would have continued into the forest as the spine of a 1930s subdivision, one that would have replaced the deep woods with large homes. The failure of this Depression-era development saw these steep lots end up in city hands as payment in lieu of back taxes, and eventually subsumed into

Had things gone differently, Thurman Street would have continued into the forest as the spine of a 1930s subdivision, one that would have replaced the deep woods with large homes. The failure of this Depression-era development saw these steep lots end up in city hands as payment in lieu of back taxes, and eventually subsumed into  But where are the Forest Parks of the future? Despite

But where are the Forest Parks of the future? Despite  As an urban planner, I often try to provide connections to nature in town and neighborhood plans. Even something as simple as a trailhead sign and a narrow path can suffice to entice us into the tangled, mysterious world beyond. A popular trend in landscape architecture features the design of children’s “nature-play” areas, which mimic unstructured, unsupervised forest adventures. As fabricated, ersatz nature, this is not ideal. But isn’t it better than screen time?

As an urban planner, I often try to provide connections to nature in town and neighborhood plans. Even something as simple as a trailhead sign and a narrow path can suffice to entice us into the tangled, mysterious world beyond. A popular trend in landscape architecture features the design of children’s “nature-play” areas, which mimic unstructured, unsupervised forest adventures. As fabricated, ersatz nature, this is not ideal. But isn’t it better than screen time?