Find your wild in Cascade Locks

Robert Weinman

Some wild areas refuse to be tamed. Cascade Locks, a small, quiet city nestled in the heart of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, is one: a place where even the mighty Columbia River bowed to the forces of nature.

What many in The Intertwine don’t realize is just how close they are to Cascade Locks, home of the massive landslides that, one thousand years ago, stopped the river temporarily to create a “Bridge of the Gods.”

Native American legend has it that with this land bridge, the gods could cross the river without getting their feet wet (because no one likes wet feet, apparently).

Native American legend has it that with this land bridge, the gods could cross the river without getting their feet wet (because no one likes wet feet, apparently).

Native Americans have gathered at Cascade Locks for thousands of years, and the Warm Springs, Yakama, Nez Perce, and Umatilla treaty tribes are still very active and influential in the region. But now a new group is showing up: outdoor recreation fans drawn -- by design -- to the wild nature of Cascade Locks.

In 2011, the City of Cascade Locks adopted a vision statement and economic development strategy aimed at balancing recreation with commercial and industrial business development. In 2012, a recreational trails plan called “Connect Cascade Locks” was put into action, with recommendations ranging from wayfinding signage and bike racks to fostering a locally-based trail stewardship group that could help build and maintain new trails in partnership with the US Forest Service.

In 2011, the City of Cascade Locks adopted a vision statement and economic development strategy aimed at balancing recreation with commercial and industrial business development. In 2012, a recreational trails plan called “Connect Cascade Locks” was put into action, with recommendations ranging from wayfinding signage and bike racks to fostering a locally-based trail stewardship group that could help build and maintain new trails in partnership with the US Forest Service.

It’s no wonder that Cascade Locks sees new value in its proximity to the wild. Multiple hiking trails converge right here, including the legendary Pacific Crest Trail, which drops four thousand vertical feet over nine miles to cross the Columbia River at the iconic steel Bridge of the Gods, built in 1920. There’s also a growing system of nearby mountain bike trails, which now host events like the Short Track Mountain Bike Championships, Dimwits With Bright Lights Night Rides, and Take a Kid Mountain Biking Day.

It’s no wonder that Cascade Locks sees new value in its proximity to the wild. Multiple hiking trails converge right here, including the legendary Pacific Crest Trail, which drops four thousand vertical feet over nine miles to cross the Columbia River at the iconic steel Bridge of the Gods, built in 1920. There’s also a growing system of nearby mountain bike trails, which now host events like the Short Track Mountain Bike Championships, Dimwits With Bright Lights Night Rides, and Take a Kid Mountain Biking Day.

For those seeking smoother terrain, the newly restored nearby Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail conducts bikers and walkers from Troutdale to Cascade Locks without using Interstate 84.

For those seeking smoother terrain, the newly restored nearby Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail conducts bikers and walkers from Troutdale to Cascade Locks without using Interstate 84.

And now, in close partnership with The Columbia Gorge Racing Association, Cascade Locks has transformed itself into one of the top sailing locations in North America, promoting world-class regattas and clinics for small boat sailing.

With the addition of a series of new water trails ranging from beginner to expert, kayakers and paddlers can now weave their way through protected coves, secluded lakes, or through the challenging whirlpools and eddies of the original locks.

With the addition of a series of new water trails ranging from beginner to expert, kayakers and paddlers can now weave their way through protected coves, secluded lakes, or through the challenging whirlpools and eddies of the original locks.

Outdoor recreation is already paying off here, with new businesses including a waterfront brewery as well as a fresh fish market run by a local family from the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Other businesses are expanding, from an ice cream stand to a restored ale house and the famous Charburger Restaurant.

And some of the plan's more ambitious features are just about to set sail.

And some of the plan's more ambitious features are just about to set sail.

“One of our most ambitious projects is the proposed riverfront beach expansion,” said Holly Howell of the Port of Cascade Locks.

“For the past five years we have worked with the Army Corps of Engineers, Oregon Department of State Lands, the four Columbia River Treaty Tribes, and the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission to design and develop a beach that will increase recreation and tribal fishing access while improving natural habitat,” Howell added.

After a day kayaking and standup paddling on the river, one recent visitor to Cascade Locks -- Moses Winston of New Mexico -- sat down at Thunder Island Brewing, the new microbrewery, and offered this apt toast to the setting sun:

After a day kayaking and standup paddling on the river, one recent visitor to Cascade Locks -- Moses Winston of New Mexico -- sat down at Thunder Island Brewing, the new microbrewery, and offered this apt toast to the setting sun:

“Find your wild, refuse to be tamed, come to Cascade Locks.”

Bob Weinman is a coordinator with the office of Economic and Workforce Development at Mt Hood Community College. A resident of Hood River, Oregon, Bob is also an avid outdoor enthusiast in paddling, hiking and sailing and finds Cascade Locks one of the new hidden treasures of the Pacific Northwest for outdoor recreation.

Bob Weinman is a coordinator with the office of Economic and Workforce Development at Mt Hood Community College. A resident of Hood River, Oregon, Bob is also an avid outdoor enthusiast in paddling, hiking and sailing and finds Cascade Locks one of the new hidden treasures of the Pacific Northwest for outdoor recreation.

OWEB has supported the Deschutes partnership since 2008, and its accomplishments are impressive. The success of this partnership, and others like it, has led OWEB to create a new program, which we call “focused investment partnerships,” that promote landscape-scale collaboration to achieve prioritized outcomes.

OWEB has supported the Deschutes partnership since 2008, and its accomplishments are impressive. The success of this partnership, and others like it, has led OWEB to create a new program, which we call “focused investment partnerships,” that promote landscape-scale collaboration to achieve prioritized outcomes. This past January, OWEB held its quarterly meeting in Portland, where

This past January, OWEB held its quarterly meeting in Portland, where  Tom Byler is the Executive Director of the

Tom Byler is the Executive Director of the  When you’re out walking, paddling, bird watching and otherwise enjoying The Intertwine, you probably notice some amazing natural gems, as well as some signals that all is not well with nature in our urban environment.

When you’re out walking, paddling, bird watching and otherwise enjoying The Intertwine, you probably notice some amazing natural gems, as well as some signals that all is not well with nature in our urban environment. For example, the Willamette River in Portland is now

For example, the Willamette River in Portland is now

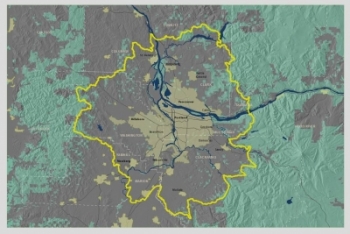

The City of Portland and many of our partners have been monitoring and tracking things like water quality, tree canopy and fish populations for many years. But, we had different types of information for different areas and purposes, making it hard to compare data over time and across the city. In 2010, Portland started a new

The City of Portland and many of our partners have been monitoring and tracking things like water quality, tree canopy and fish populations for many years. But, we had different types of information for different areas and purposes, making it hard to compare data over time and across the city. In 2010, Portland started a new  Just like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or your 5th grader’s report card, watershed report cards and indices aren’t perfect. They don’t tell the whole story. But, they’re one way to help spur the conversation. The

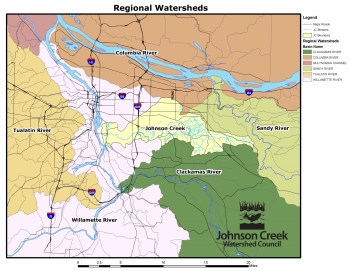

Just like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or your 5th grader’s report card, watershed report cards and indices aren’t perfect. They don’t tell the whole story. But, they’re one way to help spur the conversation. The  Like trails, streams need to be connected. Stream connectivity grades range from Bs to a D. Portland has nearly 300 miles of rivers and streams in the city, but they’re not all connected and flowing freely. Some, like Johnson Creek and its tributaries, receive relatively good scores for connectivity. However, many

Like trails, streams need to be connected. Stream connectivity grades range from Bs to a D. Portland has nearly 300 miles of rivers and streams in the city, but they’re not all connected and flowing freely. Some, like Johnson Creek and its tributaries, receive relatively good scores for connectivity. However, many  We’ve come a long way on water quality, and we have a long way still to go. Overall water quality grades are “fair” across most watersheds, but certain individual indicators have very good scores and others have very poor scores. Portland conquered a major challenge,

We’ve come a long way on water quality, and we have a long way still to go. Overall water quality grades are “fair” across most watersheds, but certain individual indicators have very good scores and others have very poor scores. Portland conquered a major challenge,  stormwater infrastructure, as well as actions by individual Portlanders. Water temperature and mercury are also significant problems, with regional and global causes. Some of these pollutants don’t impact human contact with the water, but are bad for migratory salmon, the food chain, and for people who rely on resident fish to feed their families.

stormwater infrastructure, as well as actions by individual Portlanders. Water temperature and mercury are also significant problems, with regional and global causes. Some of these pollutants don’t impact human contact with the water, but are bad for migratory salmon, the food chain, and for people who rely on resident fish to feed their families. with concrete or missing buffers of plants and trees. Factors like this make it hard for native fish and wildlife to thrive.

with concrete or missing buffers of plants and trees. Factors like this make it hard for native fish and wildlife to thrive. Sara Culp works at Portland’s

Sara Culp works at Portland’s  In my role as Willamette River evangelist and Ringleader of the not-for-profit organization

In my role as Willamette River evangelist and Ringleader of the not-for-profit organization  While much remains to be done to protect the fish and wildlife that share the river with us, including salmon that pass through during their migration, we humans at least are safe to recreate in the river. Issues like cleaning up the city’s Superfund site should be a huge priority, to offer the same protection for the critters that rely on the river. My hat’s off to groups dedicated to this objective, including Willamette Riverkeeper, the Audubon Society of Portland and many others.

While much remains to be done to protect the fish and wildlife that share the river with us, including salmon that pass through during their migration, we humans at least are safe to recreate in the river. Issues like cleaning up the city’s Superfund site should be a huge priority, to offer the same protection for the critters that rely on the river. My hat’s off to groups dedicated to this objective, including Willamette Riverkeeper, the Audubon Society of Portland and many others. To engage individuals and extend our reach in the community, last summer the Human Access Project launched the

To engage individuals and extend our reach in the community, last summer the Human Access Project launched the  Our River Hugger group started in spring 2014 with 12 people and one safety kayaker. By the last swim of the summer, our group had grown to 38 people with three safety kayakers. Overall, 80 individuals took part at some point during the season. We designed and produced our own River Hugger swim caps, and gained attention while building a new community of river activists.

Our River Hugger group started in spring 2014 with 12 people and one safety kayaker. By the last swim of the summer, our group had grown to 38 people with three safety kayakers. Overall, 80 individuals took part at some point during the season. We designed and produced our own River Hugger swim caps, and gained attention while building a new community of river activists.  We are hopeful that the River Hugger Swim Team will become another tool to help the Portland community overcome its fear and negative feelings about the Willamette River and to make a commitment to addressing much needed additional protections and ecological restoration.

We are hopeful that the River Hugger Swim Team will become another tool to help the Portland community overcome its fear and negative feelings about the Willamette River and to make a commitment to addressing much needed additional protections and ecological restoration.

For the past century, cities have been built to encourage automobile traffic. This model generally excludes green spaces, which are so vital for our mental health and spiritual well-being. What I find so thrilling about the Portland area—and the work of The Intertwine partners in particular—is using green space as the basis for building a new transportation paradigm for non-motorized travel.

For the past century, cities have been built to encourage automobile traffic. This model generally excludes green spaces, which are so vital for our mental health and spiritual well-being. What I find so thrilling about the Portland area—and the work of The Intertwine partners in particular—is using green space as the basis for building a new transportation paradigm for non-motorized travel.

spawning ground for threatened coho salmon. Chinook salmon, steelhead trout, and cutthroat trout also spawn here. Beaver build dams in Johnson Creek.

spawning ground for threatened coho salmon. Chinook salmon, steelhead trout, and cutthroat trout also spawn here. Beaver build dams in Johnson Creek.  There’s a palpable excitement and spirit of volunteerism in our metro area around participating in this restoration effort. Last year, more than 1,300 individuals volunteered to plant trees, remove invasive vegetation, monitor stream conditions and clean up garbage in the Johnson Creek stream corridor through our Council’s projects. To me, this groundswell speaks not only to the hunger to be around healthy natural areas, but to be part of a community that shares these values, as well.

There’s a palpable excitement and spirit of volunteerism in our metro area around participating in this restoration effort. Last year, more than 1,300 individuals volunteered to plant trees, remove invasive vegetation, monitor stream conditions and clean up garbage in the Johnson Creek stream corridor through our Council’s projects. To me, this groundswell speaks not only to the hunger to be around healthy natural areas, but to be part of a community that shares these values, as well. Daniel Newberry is the executive director of the Johnson Creek Watershed Council. He moved to Oregon in 1993 after earning a master’s degree in forest science, concentrating in forest hydrology and watershed management. He has also served as the executive director of the Applegate River Watershed Council and the Siskiyou Field Institute, and has worked as a tribal and federal hydrologist, and as a consultant.

Daniel Newberry is the executive director of the Johnson Creek Watershed Council. He moved to Oregon in 1993 after earning a master’s degree in forest science, concentrating in forest hydrology and watershed management. He has also served as the executive director of the Applegate River Watershed Council and the Siskiyou Field Institute, and has worked as a tribal and federal hydrologist, and as a consultant.

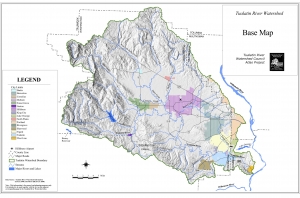

This shallow gradient creates a wide floodplain that has attracted humans and wildlife since the last Ice Age flood inundated the valley. Over half a million people now call the Tualatin Valley home. It is forested and farmed, homesteaded and housing developed, citified and industrialized. Yet, if you know where to look, you can still find a sense of place that might have been experienced by the native Atfalati, the area’s first residents. And, it may well be the birds that help you find it.

This shallow gradient creates a wide floodplain that has attracted humans and wildlife since the last Ice Age flood inundated the valley. Over half a million people now call the Tualatin Valley home. It is forested and farmed, homesteaded and housing developed, citified and industrialized. Yet, if you know where to look, you can still find a sense of place that might have been experienced by the native Atfalati, the area’s first residents. And, it may well be the birds that help you find it. Jackson Bottom Wetlands Preserve is owned and managed by the City of Hillsboro Parks & Recreation Department. Its 635 acres are part of almost 3,000 acres of undeveloped riparian, wetland and agricultural habitat along the river. During the dry season you can explore the four miles of walking trails from dawn to dusk; the river overflows in winter and floods much of the preserve. All year round, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., volunteers welcome you to the education building with a nature store, classroom, office space, pollinator garden, demonstration garden and natural history displays — including an actual bald eagle nest.

Jackson Bottom Wetlands Preserve is owned and managed by the City of Hillsboro Parks & Recreation Department. Its 635 acres are part of almost 3,000 acres of undeveloped riparian, wetland and agricultural habitat along the river. During the dry season you can explore the four miles of walking trails from dawn to dusk; the river overflows in winter and floods much of the preserve. All year round, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., volunteers welcome you to the education building with a nature store, classroom, office space, pollinator garden, demonstration garden and natural history displays — including an actual bald eagle nest. Educational programming serves over 5,000 visiting school children, and another 1,000 are reached by traveling programs. Community and adult education programming is increasing with the recent addition of a Nature Program Supervisor to the Jackson Bottom staff.

Educational programming serves over 5,000 visiting school children, and another 1,000 are reached by traveling programs. Community and adult education programming is increasing with the recent addition of a Nature Program Supervisor to the Jackson Bottom staff.

With credit and a humble apology, I take the title of Norman Maclean’s book A River Runs Through It and strive to make it more personal and inclusive by replacing “It” with “Us.”

With credit and a humble apology, I take the title of Norman Maclean’s book A River Runs Through It and strive to make it more personal and inclusive by replacing “It” with “Us.” Call it the happenstance of human migration, the mistakes of our mothers and fathers, progress, or opportunity; this river, which many of us see each day, has defined where we live.

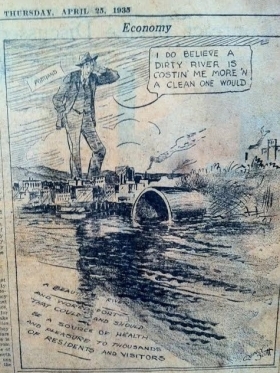

Call it the happenstance of human migration, the mistakes of our mothers and fathers, progress, or opportunity; this river, which many of us see each day, has defined where we live. As the Willamette Valley changed, so did the river. Where once grasslands, oak savannas, meanders and floodplains made for a natural balance of nature, our river has now has been “tamed” into a channel.

As the Willamette Valley changed, so did the river. Where once grasslands, oak savannas, meanders and floodplains made for a natural balance of nature, our river has now has been “tamed” into a channel. We have used the Willamette for commerce, manufacturing, ship-building, industry and recreation. Yet for centuries, this river was a major source of life giving food and materials to the Native Americans. You can see where the uses conflicted with one another.

We have used the Willamette for commerce, manufacturing, ship-building, industry and recreation. Yet for centuries, this river was a major source of life giving food and materials to the Native Americans. You can see where the uses conflicted with one another. For over 18 years, I had the honor of serving Oregon as the executive director of Governor Tom McCall’s non-profit organization, SOLVE.

For over 18 years, I had the honor of serving Oregon as the executive director of Governor Tom McCall’s non-profit organization, SOLVE.

From 1990 to 2008, Jack McGowan was Executive Director of SOLVE, a coastal beach cleanup which has now spread to over 100 foreign countries. Over the past five decades, he has worked as an on-air radio and television host, assistant to Portland Mayor J.E. Bud Clark, producer of the Mt. Hood Festival of Jazz, and Public Relations Director for the Oregon Zoo. In 2013, the Port of Portland asked Jack to create the podcast series "One River, Many Voices," which interviews over 40 representatives with a stake in the restoration of the Willamette River.

From 1990 to 2008, Jack McGowan was Executive Director of SOLVE, a coastal beach cleanup which has now spread to over 100 foreign countries. Over the past five decades, he has worked as an on-air radio and television host, assistant to Portland Mayor J.E. Bud Clark, producer of the Mt. Hood Festival of Jazz, and Public Relations Director for the Oregon Zoo. In 2013, the Port of Portland asked Jack to create the podcast series "One River, Many Voices," which interviews over 40 representatives with a stake in the restoration of the Willamette River. On May 20th, Portland voters decide the fate of the City’s

On May 20th, Portland voters decide the fate of the City’s  For months, local media have rained down coverage on the Measure: profiling its backers, which include

For months, local media have rained down coverage on the Measure: profiling its backers, which include  “Innovative

“Innovative  “BES’s

“BES’s  Through storytelling outlets like

Through storytelling outlets like

We believe the project site, the 22-acre former Blue Heron paper mill in Oregon City, could someday serve as an economic engine, a waterfront destination, a unique habitat, a window into Oregon’s past – and a bold step into our future.

We believe the project site, the 22-acre former Blue Heron paper mill in Oregon City, could someday serve as an economic engine, a waterfront destination, a unique habitat, a window into Oregon’s past – and a bold step into our future. The former mill is for sale, but the site’s complexity and risks have required a careful and methodical transition to new uses. With the help of our consulting team, Oregon City, Clackamas County, Metro, the State of Oregon, and the property’s bankruptcy trustee, we have been working closely over the past year to develop a

The former mill is for sale, but the site’s complexity and risks have required a careful and methodical transition to new uses. With the help of our consulting team, Oregon City, Clackamas County, Metro, the State of Oregon, and the property’s bankruptcy trustee, we have been working closely over the past year to develop a  The Riverwalk we've proposed in the master plan would be a catalyst for economic development in Oregon City, and also enhance the site's development value by demonstrating the public’s commitment to improvements. It would attract visitors and generate momentum for continued implementation of the master plan.

The Riverwalk we've proposed in the master plan would be a catalyst for economic development in Oregon City, and also enhance the site's development value by demonstrating the public’s commitment to improvements. It would attract visitors and generate momentum for continued implementation of the master plan. You can help shape that change, by joining our

You can help shape that change, by joining our  Ken Pirie is a senior associate with

Ken Pirie is a senior associate with

David Cohen, The Intertwine Alliance's Program Manager, has close to 30 years of non-profit management and program development experience. For the four years prior to joining our team, he served as the Executive Director of the

David Cohen, The Intertwine Alliance's Program Manager, has close to 30 years of non-profit management and program development experience. For the four years prior to joining our team, he served as the Executive Director of the