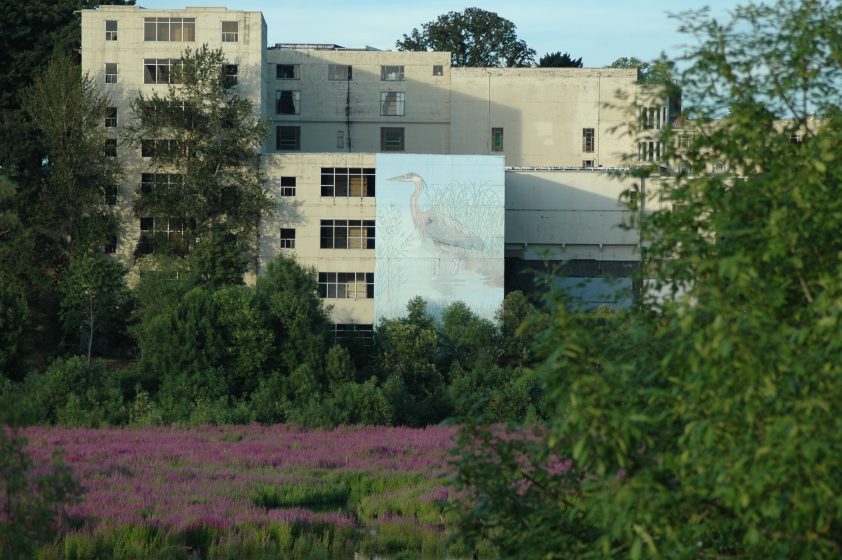

A 70-foot heron transforms a lifeless wall

By Mike Houck, August 3 2016

Thank you to The Nature of Cities blog for permission to reprint this article originally published June 23, 2016.

Recently, The Nature of Cities launched Up Against the Wall: A Gallery of Nature-Themed Graffiti and Street Art, soliciting graffiti and murals celebrating nature in the city. I submitted images of what I believe to be the largest hand-painted wall mural on a building in North America.

When it comes to community murals, nothing substitutes for persistence and perseverance. But the results are worth the effort.

I frequently lead natural history walks around the 160-acre Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge, Portland’s first official urban wildlife refuge that lies on the east bank of the Willamette River, not far from the city center. The mural overlooks the refuge, and the tale of its origins invariably intrigues my guests. I thought the making of the mural, particularly to those contemplating a large-scale project, might be of interest to readers. I certainly learned a lot by working with muralists, artists, building owners, foundations and the public while helping create the 55,000-square-foot wetland mosaic.

In 1986, I had convinced our Mayor, Bud Clark, and Portland city council to adopt the great blue heron as the city’s official city bird. For the past 30 years, we have held an annual Great Blue Heron Week. I had been thinking for several years after the heron’s induction as the city’s nature icon that it would be cool, as those who watch Portlandia will recognize, to “put a bird on a wall, and call it art.” I knew which wall I wanted to put a bird on, but had no idea how I might pull it off.

In the winter of 1991, walking along one of Portland’s thoroughfares, my eye was drawn to an enormous, beautiful representation of a 40-foot tall Blitz-Weinhard beer bottle. After much shouting and gesticulating to the painter perched 70 feet above me, I learned that he worked for the Portland-based ArtFX Murals, whose office was just around the corner. Finding the office door wide open, with no one in sight, I left a Post-It note indicating I wanted them to volunteer to paint a great blue heron mural on a huge building overlooking the refuge.

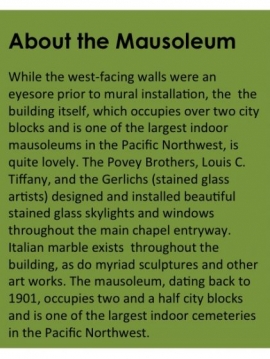

That evening, ArtFX’s Mark Bennett called to say he lived directly across the Willamette River from the building I had in mind, the Portland Memorial Mausoleum. He said he was sick of looking at the “butt ugly,” grey, west-facing wall of the building, which loomed over the wetlands below. Sure, he said, “give me $1,500 to pay an assistant, and I will donate my time.”

With an artist in hand, I approached the mausoleum’s owner who, knowing the building’s west-facing wall was an eyesore to the neighborhood, said he’d consider it, but expressed concern that loved ones whose relatives were interred in the mausoleum-crematorium might oppose the project. Audubon Society of Portland volunteer and medical illustrator Lynn Kitagawa had donated a beautiful watercolor for the mural template. So, I conducted my own opinion poll. I bought an easel and mounted Kitagawa’s watercolor in the mausoleum’s foyer with a note asking for feedback. Visitors all gave a thumb’s up, which resulted in permission to use one of the mausoleum’s west-facing walls as a canvas.

With an artist in hand, I approached the mausoleum’s owner who, knowing the building’s west-facing wall was an eyesore to the neighborhood, said he’d consider it, but expressed concern that loved ones whose relatives were interred in the mausoleum-crematorium might oppose the project. Audubon Society of Portland volunteer and medical illustrator Lynn Kitagawa had donated a beautiful watercolor for the mural template. So, I conducted my own opinion poll. I bought an easel and mounted Kitagawa’s watercolor in the mausoleum’s foyer with a note asking for feedback. Visitors all gave a thumb’s up, which resulted in permission to use one of the mausoleum’s west-facing walls as a canvas.

With artist and canvas on board, I went to the local Miller Paint store, a century old Portland firm, which donated the paint. Finally, a local resident who overlooked the wetlands rounded up the scaffolding.

In May of 1991, we dedicated the 70-foot-high, 50-foot-wide heron, and the mausoleum owners received so many thank-you calls and letters that Bennett, along with the owners, asked if we could do the entire building. Mark even drafted up a sketch. Unfortunately, the $20,000 price tag was beyond my means. So, we celebrated the heron mural and left it at that.

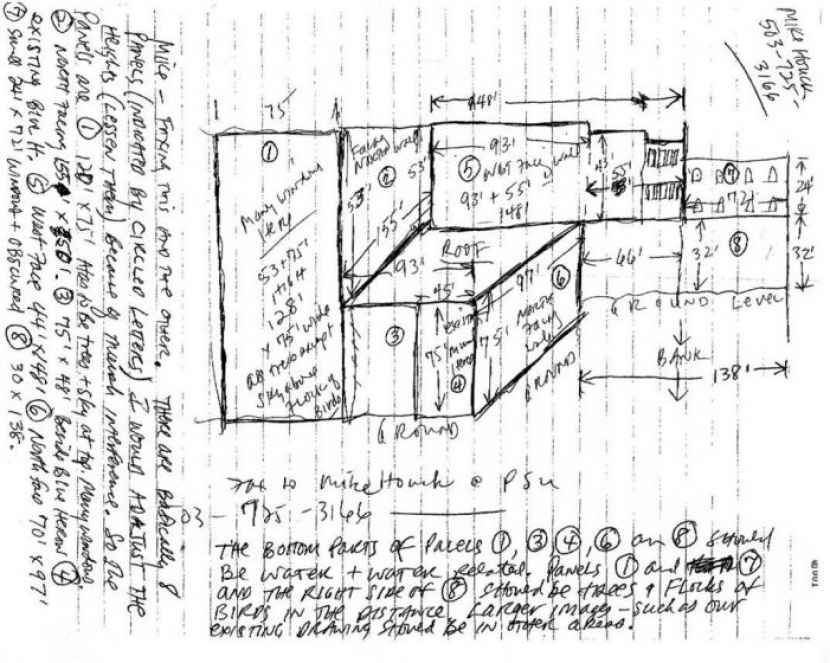

Painting the Big One

Twenty-seven years later, Bennett called me out of the blue, asking, “When are we gonna finish that building?” A few hours later, we stood on the bluff overlooking the wetland and mausoleum, kicking the dirt, appraising the size of the project and eyeing the now-faded heron which was framed by dull grey walls studded with quarter-inch rebar. Bennett said, “My son Shane and I really want to finish this job. We’ll do it for $30,000.” Seeing the “sticker-shock” expression on my face, he quickly informed me a commercial project that size would be $180,000. A great deal, but still … time to get to work!

Adopting the design concept

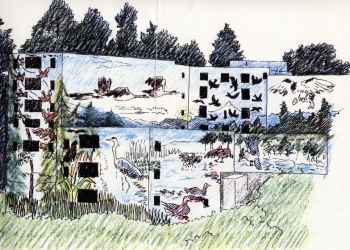

Bennett had worked up a general design with the proviso that it would depict resident wildlife. I asked Audubon’s conservation director, Bob Sallinger, to share a few pints of beer with local artist and muralist Dan Cohen and Mark’s son, Shane, who had been 13 at the time we did the heron mural. The four of us refined Mark’s rough sketch, creating a wetland motif that featured both the wetland’s migratory and year-round residents. Cohen then created paintings that would provide the concept for each of the eight walls, two of which faced south, while the others faced west and would be visible from across the Willamette River.

Bennett had worked up a general design with the proviso that it would depict resident wildlife. I asked Audubon’s conservation director, Bob Sallinger, to share a few pints of beer with local artist and muralist Dan Cohen and Mark’s son, Shane, who had been 13 at the time we did the heron mural. The four of us refined Mark’s rough sketch, creating a wetland motif that featured both the wetland’s migratory and year-round residents. Cohen then created paintings that would provide the concept for each of the eight walls, two of which faced south, while the others faced west and would be visible from across the Willamette River.

Fundraising

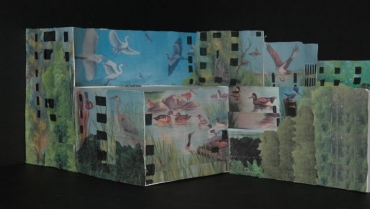

I then went to work on my least favorite activity—writing grants and begging for money. First stop, the Regional Arts and Culture Council (or RACC), without whose permission there would be no mural. Cohen and I had to attend three meetings with the Council’s mural committee, one of which involved my creating a 3-D model of the mausoleum so that they could get a better grasp of the actual design. Not only did we get permission, but RACC also provided a $10,000 grant, which opened the door to leveraging funds from other sources.

I then went to work on my least favorite activity—writing grants and begging for money. First stop, the Regional Arts and Culture Council (or RACC), without whose permission there would be no mural. Cohen and I had to attend three meetings with the Council’s mural committee, one of which involved my creating a 3-D model of the mausoleum so that they could get a better grasp of the actual design. Not only did we get permission, but RACC also provided a $10,000 grant, which opened the door to leveraging funds from other sources.

Spirit Mountain Community Fund committed the next $20,000, and Miller Paint once again donated $10,000 worth of paint. That left $30,000 to seal the deal. The city’s Bureau of Environmental Services’ Community Watershed Stewardship Program, the Willamette Fun(d) of the Oregon Community Foundation, and Portland Parks & Recreation filled the funding gap.

But wait, there’s more!

Now that I had the money, I went to the mausoleum to confirm we were ready to start work, only to find it had been sold. Panic! I had to set up a meeting with the new owners. To my great relief, the new owners had been briefed and not only gave their enthusiastic permission, but kicked in another $2,000.

Finally, we were set to begin work in early summer of 2008. We didn’t get started until fall, due to the first of what would be innumerable delays. What had begun as a three-month project dragged on for more than a year. I had to remind myself I was getting a deep, deep discount. The Bennetts had commercial projects in Los Angeles, New York City and Las Vegas. I was in no position to grouse about schedules.

Finally, we were set to begin work in early summer of 2008. We didn’t get started until fall, due to the first of what would be innumerable delays. What had begun as a three-month project dragged on for more than a year. I had to remind myself I was getting a deep, deep discount. The Bennetts had commercial projects in Los Angeles, New York City and Las Vegas. I was in no position to grouse about schedules.

Additionally, I had lost my earlier scaffolding donor after all those years, so I still had one big problem to solve. After searching for several weeks, Northwest Scaffolding Services agreed to provide the scaffolding—and although they provided it at a discount, it still turned out to be the most expensive item of the project, given it lay idle while the farther-son team worked on their paying gigs. In fact, by now I was working almost exclusively with Shane, his father having gone into semi-retirement in Costa Rica.

Modeling the Sistine Chapel

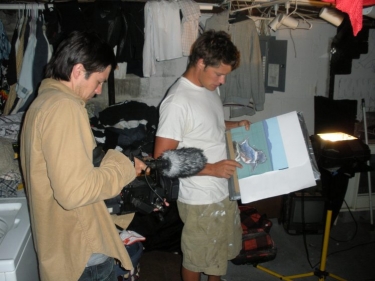

The process by which they applied the images to the mausoleum walls was similar to that used by Renaissance painters, and reputedly like Michelangelo’s technique on the Sistine Chapel.

Using images I provided, Shane shone them onto paper with an opaque projector. Behind the paper was a metal plate which, when he traced the image—feather by feather—set up an arc with his “electronic pencil.” The electric arc produced thousands of minute holes that were burned through the paper.

Using images I provided, Shane shone them onto paper with an opaque projector. Behind the paper was a metal plate which, when he traced the image—feather by feather—set up an arc with his “electronic pencil.” The electric arc produced thousands of minute holes that were burned through the paper.

Once the entire image had been transferred to paper, the gridded-out roll was taken to the scaffolding. Shane and his assistants then unrolled the paper, grid-by-grid, and daubed charcoal dust across arc-produced holes, creating a crude outline of the image on the wall.

This painstaking process was repeated hundreds of times until the composite image emerged, again, feather by feather. The resulting crude outlines guided their more refined painting.

Rebar and primer

But, once again, there’s more! As I noted at the outset, every wall was studded with thousands of quarter-inch rebar jutting several inches out from the wall. Before any work could begin, all of those metal rods had to be ground off. Then the walls had to be power washed and a coat of primer applied. Throughout the project, there always seemed to be one more step before work could progress.

First up to be painted were the hooded mergansers, an osprey grasping a steelhead trout in its talons, and a red-tailed hawk. Before long, the uppermost south-facing wall had several huge great egrets, giant great blue herons in flight, and a peregrine falcon surrounded by a flock of Vaux’s swifts.

First up to be painted were the hooded mergansers, an osprey grasping a steelhead trout in its talons, and a red-tailed hawk. Before long, the uppermost south-facing wall had several huge great egrets, giant great blue herons in flight, and a peregrine falcon surrounded by a flock of Vaux’s swifts.

Shane, Dan and their crew finished two huge black cottonwoods on the largest west-facing wall, with a perching bald eagle and a great horned owl on their branches. Dan took some artistic license by inserting an “eye” in one of the tree’s knotholes and huge, furry feet on the great horned owl, both of which are visible only from the  trail that passes at the foot of the building.

trail that passes at the foot of the building.

The most fascinating process, however, was watching the great blue herons and great egrets, with their fantastic wingspans, emerge day-to-day.

After disassembling and moving the scaffolding several times, the final south-facing wall was almost finished. As I was photographing Shane on that last south wall, a female Anna’s hummingbird kept buzzing around his face. He asked what it was, and I sent him an image of the more colorful male Anna’s that evening. Two days later, I was delighted to see he’d added another image to the wall—the vibrant Anna’s male, the mural’s final image.

Remembering how the original heron had faded, the final touch was a UV coating, ensuring the murals would remain vibrant for many years.

On October 2, 2009, the mural was dedicated, 28 years after the great blue heron adorned the mausoleum. A hundred people walked from Portland Memorial’s chapel onto the roof to view the mural up close. At more than 50,000 feet, Shane, Mark and Dan had installed the largest hand-painted wall mural in North America. What had been a “butt ugly” eyesore for many decades  was now a colorful invitation to cyclists, runners and walkers to slow down a bit as they traversed the newly completed Springwater on the Willamette Trail, which bordered the western edge of the wetlands and afforded a spectacular view of the mausoleum and a chance to appreciate the city’s first official urban wildlife refuge.

was now a colorful invitation to cyclists, runners and walkers to slow down a bit as they traversed the newly completed Springwater on the Willamette Trail, which bordered the western edge of the wetlands and afforded a spectacular view of the mausoleum and a chance to appreciate the city’s first official urban wildlife refuge.

The final touch was the unveiling and installation of a portrait of the wetland’s early advocate, Al Miller. Forty-six years earlier, Al had recruited me and several other graduate students from a Portland State University seminar to help convince the city not to  fill the wetlands, a campaign that succeeded in 1988 with the city council’s adoption of the Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge management plan, which I and two others had written.

fill the wetlands, a campaign that succeeded in 1988 with the city council’s adoption of the Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge management plan, which I and two others had written.

I gave pictures of Al to Dan Cohen, who captured Al’s persona, binoculars and all, in a portrait, which was then mounted in one of the mausoleum’s west-facing walls. Today, Al overlooks the wetlands that he and others worked in the 1960s and into the 1970s so hard to protect.

Lessons learned

First and foremost, my motto is “endless pressure, endlessly applied.” Nothing substitutes for persistence and perseverance. You’ve got to believe and create your own reality.

Second, get your permit(s) and first funding and use it to leverage additional funding. If I had not secured the permit and funding from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, I do not think the project would have proceeded.

Third, “run to daylight," an old American football adage that instructs a player to find gaps through which to make a play. If the hole the play called for closes, look to “daylight”—another opportunity to get it done.

Third, “run to daylight," an old American football adage that instructs a player to find gaps through which to make a play. If the hole the play called for closes, look to “daylight”—another opportunity to get it done.

Fourth, find a partner as passionate as you, or perhaps more so. In my case, Mark and Shane Bennett had at least as much passion for success as I did in this project, which surprised and delighted me.

Finally, I think among the many reasons that urban nature advocates need to expand their partnerships is the need to connect art with nature. Look for partnerships with groups such as our Regional Arts and Culture Council. As it turns out, I was unaware that Portland has an active mural culture. Had I known this, I would have reached out to them for support. Later, I testified before Portland City Council to support that community. Diversifying urban nature advocacy should  include the arts, which is why I am pleased that The Nature of Cities launched Up Against the Wall: A Gallery of Nature-Themed Graffiti and Street Art.

include the arts, which is why I am pleased that The Nature of Cities launched Up Against the Wall: A Gallery of Nature-Themed Graffiti and Street Art.

Afterward

Sadly, the same winter that this project was finished, Shane was killed in a Colorado snowmobile accident. Poignantly, as his mourners walked onto the mausoleum roof, a bald eagle—one of Shane’s favorite birds and one that routinely soared above him while he worked on the mural—flew directly overhead, circled a few times, and glided west over the refuge and Willamette River.

Mark now lives full-time in Costa Rica and Dan continues his artwork in Portland. I, fortunately, still lead tours around the two-mile loop trail, and have the opportunity to tell the mural story on each circuit of the Bottoms.

Afterward, part two

8/5/16 - The mural continues to inspire people far and wide. After reading my post on The Nature of Cities website, the Veterans Administration Hospital in Portland contacted Mark Bennett, owner of ArtFX murals, to see if he would be willing to paint a large mural depicting the surrounding forest. Mark gave them an enthusiastic yes, and will be meeting with them soon to scope out the project. Before long there will be another nature mural here in The Intertwine!

Mike Houck, executive director of the

Mike Houck, executive director of the

Comments

Anatomy of a mural-

Add new comment