Portland's new Watershed Report Cards

By Sara Culp, October 5 2015

When you’re out walking, paddling, bird watching and otherwise enjoying The Intertwine, you probably notice some amazing natural gems, as well as some signals that all is not well with nature in our urban environment.

When you’re out walking, paddling, bird watching and otherwise enjoying The Intertwine, you probably notice some amazing natural gems, as well as some signals that all is not well with nature in our urban environment.

For example, the Willamette River in Portland is now safe for recreation most of the year. Osprey, eagles and herons soar right through downtown. On the other hand, this summer we saw Chinook salmon dying in the river’s warm water.

For example, the Willamette River in Portland is now safe for recreation most of the year. Osprey, eagles and herons soar right through downtown. On the other hand, this summer we saw Chinook salmon dying in the river’s warm water.

Our region’s parks and natural areas are some of the best in the nation, and Portland ranks as a Top City for Wildlife. But a local bird, the streaked horned lark, recently made the list of threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

Do you ever find yourself wondering how it all adds up? How would the Willamette River or Tryon Creek rate on a grade scale?

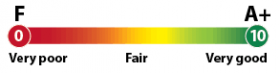

This year, the City of Portland launched its first set of Watershed Report Cards. The goal is to take reams of complicated scientific data and roll it into at-a-glance grades that can help Portlanders understand current conditions in their local watersheds.

This year, the City of Portland launched its first set of Watershed Report Cards. The goal is to take reams of complicated scientific data and roll it into at-a-glance grades that can help Portlanders understand current conditions in their local watersheds.

We’ve long had local goals and policies -- and strong public advocacy -- for our rivers and streams. Healthy watersheds are good for people, fish and wildlife. With Watershed Report Cards, we now have a better way to show where we are in meeting those goals, to track changes in watershed conditions over time, and to inform conversations about where we want to go as a community.

The City of Portland and many of our partners have been monitoring and tracking things like water quality, tree canopy and fish populations for many years. But, we had different types of information for different areas and purposes, making it hard to compare data over time and across the city. In 2010, Portland started a new citywide monitoring program with a consistent, efficient and cost-savings approach to measuring and tracking watershed conditions. Information from this monitoring is behind many of the grades in the new report cards.

The City of Portland and many of our partners have been monitoring and tracking things like water quality, tree canopy and fish populations for many years. But, we had different types of information for different areas and purposes, making it hard to compare data over time and across the city. In 2010, Portland started a new citywide monitoring program with a consistent, efficient and cost-savings approach to measuring and tracking watershed conditions. Information from this monitoring is behind many of the grades in the new report cards.

Portland is not alone in this effort. Watershed report cards are an increasingly common tool used by cities and regions to communicate with the public and policy makers. Report cards, indices and other types of “dashboards” can help illustrate complex environmental issues, what’s working, and where we need to do more. Chesapeake Bay and Ontario, Canada are using watershed report cards. Puget Sound has a Vital Signs dashboard. An initial report card is underway for the Mississippi River. Here in Oregon, the Willamette River Initiative is creating a report card for the entire Willamette River, slated for release later this year.

Just like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or your 5th grader’s report card, watershed report cards and indices aren’t perfect. They don’t tell the whole story. But, they’re one way to help spur the conversation. The grades in Portland’s Watershed Report Cards tell us where we are now and give us a baseline to track against in future years. Although we don’t yet have trend data for multiple years, we can compare the information to other historical data sources and see where we’ve already made progress —nitrogen levels in the Willamette River and Columbia Slough, for example.

Just like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or your 5th grader’s report card, watershed report cards and indices aren’t perfect. They don’t tell the whole story. But, they’re one way to help spur the conversation. The grades in Portland’s Watershed Report Cards tell us where we are now and give us a baseline to track against in future years. Although we don’t yet have trend data for multiple years, we can compare the information to other historical data sources and see where we’ve already made progress —nitrogen levels in the Willamette River and Columbia Slough, for example.

The report cards can help inform local policies, and help Portlanders understand where actions like planting trees and reducing the use of pesticides fit in. The report cards also support work with our partners in the region. After all, every one of “Portland’s” watersheds crosses boundaries into neighboring cities and counties.

Some highlights from the initial report cards:

Like trails, streams need to be connected. Stream connectivity grades range from Bs to a D. Portland has nearly 300 miles of rivers and streams in the city, but they’re not all connected and flowing freely. Some, like Johnson Creek and its tributaries, receive relatively good scores for connectivity. However, many streams that used to flow to the Willamette River from the city’s buttes and hills now run through pipes and culverts to reach the river, or they’re buried under development and largely lost, like Tanner Creek.

Like trails, streams need to be connected. Stream connectivity grades range from Bs to a D. Portland has nearly 300 miles of rivers and streams in the city, but they’re not all connected and flowing freely. Some, like Johnson Creek and its tributaries, receive relatively good scores for connectivity. However, many streams that used to flow to the Willamette River from the city’s buttes and hills now run through pipes and culverts to reach the river, or they’re buried under development and largely lost, like Tanner Creek.

Daylighting streams where we can – like at Spring Garden Park – and reconnecting streams to their floodplains, like at Foster Floodplain Natural Area, help restore natural systems, improve water quality, and reduce flood impacts on property.

We’ve come a long way on water quality, and we have a long way still to go. Overall water quality grades are “fair” across most watersheds, but certain individual indicators have very good scores and others have very poor scores. Portland conquered a major challenge, controlling combined sewer overflows, that many cities are just starting to tackle. E. coli bacteria and nitrogen grades get As in the Willamette River and Columbia Slough largely as a result of this work and efforts to move away from septic systems.

We’ve come a long way on water quality, and we have a long way still to go. Overall water quality grades are “fair” across most watersheds, but certain individual indicators have very good scores and others have very poor scores. Portland conquered a major challenge, controlling combined sewer overflows, that many cities are just starting to tackle. E. coli bacteria and nitrogen grades get As in the Willamette River and Columbia Slough largely as a result of this work and efforts to move away from septic systems.

However, pollution from homes, businesses and streets continues to be a problem for all of Portland’s streams and rivers. Stormwater runoff that carries pollutants like copper from car brakes and sediment into streams is our challenge now. This requires ongoing public investment in our  stormwater infrastructure, as well as actions by individual Portlanders. Water temperature and mercury are also significant problems, with regional and global causes. Some of these pollutants don’t impact human contact with the water, but are bad for migratory salmon, the food chain, and for people who rely on resident fish to feed their families.

stormwater infrastructure, as well as actions by individual Portlanders. Water temperature and mercury are also significant problems, with regional and global causes. Some of these pollutants don’t impact human contact with the water, but are bad for migratory salmon, the food chain, and for people who rely on resident fish to feed their families.

We have some great habitat in Portland, but sometimes fish and wildlife can’t get to it. Grades for habitat run the gamut, depending on the watershed, but grades for fish and wildlife are poor citywide. Gems like Forest Park, Smith and Bybee Lakes and Crystal Springs Creek are anchors of our local ecosystem. They support clean water and diverse fish and wildlife in the city, not to mention great recreation opportunities. But, culverts block migratory salmon from some of the best stream habitat, like Tryon Creek. Stream and riverbanks are armored  with concrete or missing buffers of plants and trees. Factors like this make it hard for native fish and wildlife to thrive.

with concrete or missing buffers of plants and trees. Factors like this make it hard for native fish and wildlife to thrive.

Removing or replacing culverts with modern designs (like at Crystal Springs), planting trees in neighborhoods and along stream banks, and protecting habitat connections through developed areas are actions that will help improve these grades.

New information about Portland’s Watershed Report Cards will be available periodically on our website: www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/ReportCards. You can keep up on city projects and community events for watershed health on the CityGreen Blog and on Facebook @CityGreenPortland.

Sara Culp works at Portland’s

Sara Culp works at Portland’s

Comments

Happy Valley's Scouter Mountain 600 house development project

Add new comment